A cave painting game about mammoths reveals the cycle of human greed

There isn’t much Jurassic World gets right about normal human behavior, but the desire to feel connected to the planet’s prehistoric past is one of them. “Jurassic World exists to show us how very small we are,” says the dinosaur park owner to the dinosaur park director. Of course, the desire for this connection ends up biting all the humans almost parabolically in the ass. The modern day “Indominus rex” serves eventually as a reflection of the inner monstrosities of creatures who not only face their own smallness, but try to counteract it by playing god.

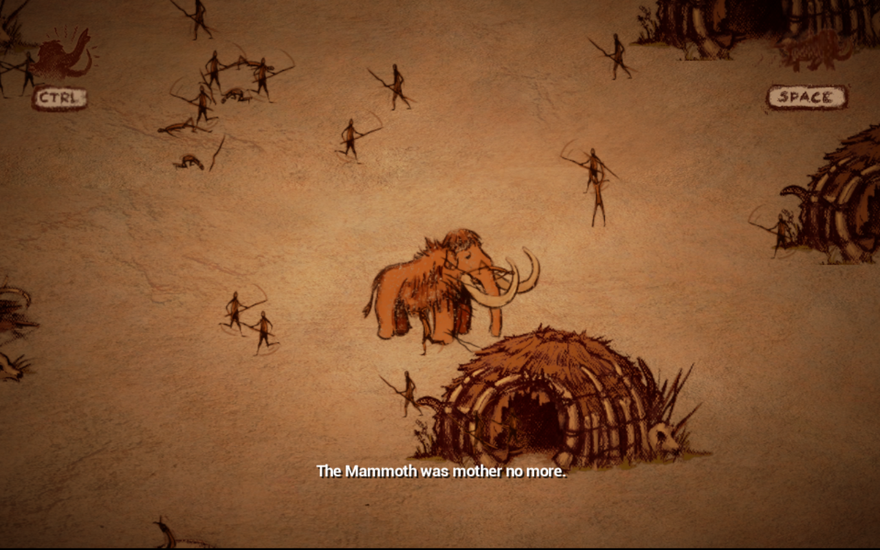

the hunters would be hunters no more

Meanwhile, in Mammoth: A Cave Painting, we find a more traditional “natural order” that is still somehow disrupted by human greed. While Jurassic World provided audiences with a physical monster to point at and blame, Mammoth: A Cave Painting demonstrates the more personal and subtle costs of human destruction. Playing as a symbol of the mammoth’s fate, the game depicts a war between a mother mammoth trying to protect her young and a band of human hunters. Both parties clash, spilling blood on either side in a seemingly unavoidable cycle of retaliation. After the human beings murder the mammoth’s young, her identity as mother is stripped away. Eventually, when the mammoth herd shrinks to the point of extinction and no more prey exists on the plains, “the hunters would be hunters no more” as well. Through the cycle of destruction, both the humans and the mammoth lose their identities and livelihoods.

As a Ludum Dare entry, Mammoth: A Cave Painting was made by Inbetween Games (made up of former Spec Ops: The Line devs) in 48 hours and abides by the game jam’s theme which states that “you are the monster.” In a post-mortem blog post on the game, team member Jan David Hassel discusses the nuances of the game’s approach to the theme. While people might try to paint the mammoth—who destroys huts and kills human hunters—as the true monster, Hassel’s intentions were far from it. Despite the fact that the story is told by the hunters themselves, with human hand prints outlining the borders of the cave painting, their villainy proves to be the story’s central moral. Since the hunters are the one’s instigating, they are the true monsters, causing the mammoth to retaliate out of a survival instinct. “Which is a comforting thought because we get to shove the blame on these external evil beings that we have no connection to—if it wouldn’t be for the fact that […] we are all the monster. We are the hunters. We as humans have eradicated more species than anything that came before us including whatever killed the motherflipping Dinosaurs. It’s quite possible that we will add ourselves to this list eventually. We are the monsters.”

We are the monsters

Mammoth: A Cave Painting even addresses the human desire to understand our own smallness. Taking inspiration from Chauvet Cave, the earliest known figurative cave drawings, “the animals are drawn immensely large in comparison to humans […] in a way that goes beyond a realistic depiction of scale and probably has much more to do with the perception of meaning and power. So scale here is based more on emotional and magical evaluations rather than the ones our modern minds would focus on.”

In the end, though, Mammoth: A Cave Painting presents one other option that absolves both the humans and the mammoth of their monstrous actions. As pointed out by commenter Hvedrung, both the hunters and the mammoth act only out of the need to eat and survive. So perhaps instead of blaming a single party, we can blame the merciless world itself for feeding on the perpetual suffering of its inhabitants.

You can play Mammoth: A Cave Painting in your browser for free.