I think it’s been 15+ years since Sega’s Team Andromeda released the most important videogame in my life. “I think” not because I question the chronology of the release of Panzer Dragoon Saga or its importance to me—no, “I think” because I question its actual existence. My brother and I speak of this game in hushed tones and already you can see its remembrance leaching out of our eyes, brows furrowing as we try to call upon some detail, sometimes any detail. I watch Youtube videos of Saga like I’m Rick Deckard looking at pictures of unicorns.

But maybe it’s better this way, this feeling that I experienced something special and I can never have it back. Rumor has it the source code’s been lost, which is fine because Panzer Dragoon Saga doesn’t belong in some online marketplace on sale for 20 bucks, it belongs as a dream in your mind that you can’t forget but can’t fully remember, and the harder you try to grip it, the more it slips. And yet still it’s there, the light it gives slowly burning an image onto a murky canvas in your temporal lobe. See, Panzer Dragoon Saga might have been a Japanese RPG about flying a dragon around in a post-post-post-apocalyptic desert, but really what it was is the parts of ourselves that we can’t touch, that don’t add up, that are entrenched in shadows … and are invaluable for it.

At the time of Panzer Dragoon Saga’s release in 1998, seminal videogame rag Next Generation gave it 4 out of 5 stars, heaping on all kinds of “best ever” superlatives but then remarking that it was too short. However, if I remember correctly—and, mind you, I probably don’t—the stars weren’t the typical black but a brilliant red, the color Next Gen reserved for “5-star” masterpieces. At the time I thought it was some weird misprint but now, looking back 16 years later, I wonder if there wasn’t some intent behind it. That missing fifth star is for the player to fill in.

It’s not so much that Panzer Dragoon Saga was short or small—though certainly it would be fair enough to call it those things, relative to similar RPG/adventure games—but rather that the fabric of its story and world had gaps like chasms. It purposefully omitted as much as it told, and sometimes told you a lot of things without bothering to tell you what those things meant or how they were connected to anything else. Early on in the game the protagonist, Edge, underwent a resurrection of sorts, maybe: an orb of light descended in a dark cavern and then dispersed a wash of radiance to race up the walls, revealing their shapes and, literally, their textures. Your dude then woke up, submerged in a pool. Yeah, I don’t know, but it felt cool. As you island-hopped between such plot points (okay, now shoot at this huge train, no questions please), propelled by inexplicable dramatic beats, you came to believe that there’s an active opposite of exposition that the artist can employ that isn‘t just silence. Integumentation? Saga’s misdirects and vagaries formed a covering, a sheath, beneath which you might presume there pulsed something alive, something growing and transforming beneath the surface. What that was, well, was up to you.

Illusive narratives and minimal mythologies are nothing new to art, of course. David Lynch has made a living off that kind of shit for years. Like Lynch, Panzer Dragoon Saga knew that this obfuscation was more palatable when served with a heavy dose of sumptuous aesthetic, and Team Andromeda had already delivered two of the most visually and aurally gorgeous on-rails shooters ever made in Panzer Dragoon and Panzer Dragoon Zwei, so they had a great template to work with in packaging the oneiric logic and elliptical rhythms of Saga. Unlike Lynch or, say, Haruki Murakami for literature, Saga was a work in an interactive medium that allowed you to pry at the corners, to try to peep through the keyholes.

The only RPG where I’ve ever been Oprah’s-Book-Club-excited

Even in the battles you’d see the elegance of Saga’s form, a mix of real-time firing and 360-degree strategic positioning offset by the limits of those positions, those angles, and the turn-based approach to the berserker and enemy attacks—freedoms and restraints intertwined, nothing pre-rendered/pre-destined but still all of it taking place in beautiful composition. The game allowed you to listen in on conversations if you stood at a short distance from the NPCs, gleaning snippets while they talked. You could dust books off the towns’ bookshelves and read them; in fact, Saga is the only RPG where I’ve ever been Oprah’s-Book-Club-excited about finding virtual documents to read, like each one was another piece to the greatest backstory never told. Saga’s world was immersive because it coolly elicited your obsession. It was that obscure object of desire, post-Bunuel.

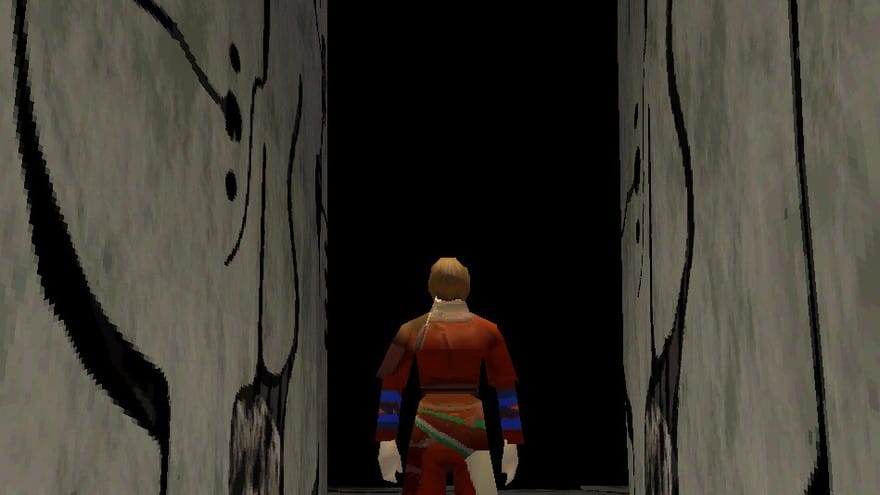

But what frustrated the teenager-me at the time and delights thirty-something-me now is that that information all read like, say, the parts of Tolkien’s Middle Earth that he didn’t bother or didn’t want to try elucidating. J.R.R. was prone to describing the shit out of a wooded knoll or what a hobbit ate for lunch, but when it came time to talk about eons past or ancient evils or music of absolute light and whatnot—to talk about things that are bigger than words—the words wisely ran scarce. You could explore the world of Saga in three dimensions, you could push at the borders, but in many places the canvas was bare and in others you’d quickly reach the edge of the painting and there you’d be given something painterly to look at, to insinuate what lays beyond. In games these days you wonder what’s behind an expertly rendered rock and all you have to do is walk around it and say, “Oh man, guys, look…more expertly rendered rocks! Plus, shrubbery!” Panzer Dragoon Saga was limited by its era and hardware, sure, but it was also very clearly aware that sometimes the most tantalizing things are the things in your own mind.

To wit, the game’s design was intensely conscious of your consciousness. Where other games of that time had limits purely of necessity, Saga was coded to speak to the codes in your brain, to give you blanks to write in, to excite your imagination. Team Andromeda’s script talked to you, not over you, and then listened to you. And, to be clear, it’s not that Panzer Dragoon Saga was scant on details or story. The thing was shy of 20 hours of gameplay but spread across four Saturn discs because of its hefty portion of cut scenes (gloriously executed and more cinematic than a dozen Pixar movies combined). But in Saga you got a lot of riddles, circles within circles. Even the textures looked ambiguous.

There was a cipher introduced in the beginning, the character Azel, an archetypal beautiful sci-fi fantasy maiden you find encased in a wall. And it only got more heady from there. Throughout the game she played the roles of muse, arch-nemesis, damsel-in-distress, nature’s nymph, science’s seer, symbol of the Unknown and Divine, subject to the attempts of the Empire (and all history’s empires, really) to be contained and controlled … and she was often many of those things at the same time. What she ultimately awakened in Edge, your avatar, was a sense of purpose in insignificance. The protagonist arc in Saga was the way it feels to look at a night sky. Is there anything more vast, enthralling, humbling? How are we not crippled and petrified by that sight? Live for the stars, die for them. Edge’s name was telling. His awakening, his awareness, meant he would always be right there, right next to the sublime, the infinite, chasing it but never part of it. But a morphing dragon is a cooler consolation prize than most of us get.

There’s another female character in Panzer Dragoon Saga that made a lasting impression on me, and she’s about as minor RPG stock as they come, so it‘s the perfect microcosm of everything that Saga did so absolutely right, how God-filled its details. The largest town in Panzer Dragoon Saga was probably the size of an Elder Scrolls outhouse, but one of its inhabitants was a female barkeep with whom you could have a bit of repartee. She would be kind to you, on the edge of flirting, but would also dismiss any advances with a bit of wit and a world-weary sort of strength. It was hard not to love her at the same time that you questioned how she felt towards you. Was she nice simply because you were a customer? The relationship made incremental progress, to the point where you started to believe that maybe, just maybe, there was something there between your pile of polygons and hers … and then, towards the end of the game (uh, spoiler alert, I guess) you got to watch from afar on your dragon as the bad guys wiped out the town and everyone in it. That one thread is representative of the larger narrative tapestry: coy but generous, smart and without bluster, a mystery, a secret garden that will always stay a million miles away, as the Boss says. This was no typical RPG townie groupie; this was something that felt so much more real, even if the actual dialogue and interaction options were more limited. Games should be gratifying but in their eagerness to gratify, developers often miss out on what their audience really wants, deep down.

I remember dropping the controller, yelling her name

In Saga the challenging/rewarding equation wasn’t just a difficulty learning curve or a series of obstacles that led to achievements and accolades or even the good vs. bad choices that some modern games use to create a simplistic moral schema; nope, it was something that was woven into the very fiber of the game’s philosophy and worldview. That your “heroic” actions indirectly led to the demise of this town lent replays of Saga a heavy sense of futility and inevitability, since doing the right thing could still result in tragic consequences. And anyway, who’s even to say what’s “right” in Saga, with our inability to comprehend the politics and the realities of everything and when fundamental deficiencies in our perception mean that, really, up is down and down is up. When the barkeep was killed I remember dropping the controller, yelling her name, raging against imperial injustices, etc. Games hadn’t done this to me before—only art had.

She was just one character in one town, gone in one flash of light. Nothing was dramatized. Edge awoke from the explosion as if from a nightmare, except that he could never go back to that town. I probably wasn’t supposed to end up caring about that girl as much as I did, and that was the grace of Saga. Its canvas was barren so you could paint. It was under-exposed so that your truth could shine brighter and with more focus through the shades of gray, however counter-intuitive that might seem. You played it in a dark room and it reflected yourself back to you, basked in the cathode glow. Then and to this day I could not tell you what happened at the end of the game. I mean, I could, but it would be pointless. It would just be visions and my feeble attempt to describe a feeling that still sends tremors through parts of myself I wouldn’t know were there but that those tremors passed through them. It would be a longing, aching never to be filled.

At the end of Wong Kar-Wai’s film In the Mood for Love, there’s a post-script that says, “He remembers those vanished years. As though looking through a dusty window pane, the past is something he could see, but not touch. And everything he sees is blurred and indistinct.” This is the shrouded world that Panzer Dragoon Saga creates, destroying our common notion of the present. Instead, it is our mythic future viewed as the fractured past. In this way it dissociates the player from how easily we take for granted the tangible and the now, and presents the intangible and the lost-to-time so that they are what’s present in the game‘s interactive moment. But, no, you can’t really touch them, it’s a videogame; its coup is that out of its restrictions it fashions artistic strengths and aligns its narrative linearity with the trappings of how we experience time. Feel civilization’s ashes fall through your fingers. Your hands are pressed against that dusty window pane, but the things you think you see on the other side of that glass darkly, that’s the stuff you really believe in, that’s the stuff you will dream of, even as the memory fades. Five stars, forever.

(Header image credit: Arzach by Moebius; via Will of the Ancients)