Pavilion and the maze as metaphor

When I was younger, I got lost in the works of Jorge Luis Borges. In my hubris, I assumed I “got” him in a way that would let me use the tools of literary study to recognize patterns, symbols, and themes. His hermetic prose held secrets that I thought I had unlocked in my sophomoric self-satisfaction. I assured myself that knowing Borges’ favorite subjects, like mazes and infinite libraries, are actually metaphors for the text itself was a revelation that only I and a few select others could hold dear.

I was wrong, of course. Not about the obvious readings, but about the uniqueness of my perspective—people have been reading and puzzling Borges’ work for far longer than I’ve been alive, each insight more clever than any I could’ve conceivably offered. But I didn’t know that at the time, not from the safety of my dorm room in Jackson, Mississippi. Instead, I obsessively stumbled toward some kernel of knowledge sealed away in the alleys of the text, certain that I had unearthed something new.

toying with the pieces of the game like a writer constructing a sentence

Until I began playing Chapter 1 of Visiontrick Media’s Pavilion, I hadn’t thought about my early readings of Borges for a long time—almost long enough to seal them away in that vault we all have for storing embarrassing moments. Having played several puzzle games in which I help some unnamed protagonist perform a series of tasks to chase some ambiguous goal, I wondered immediately what this game could show me that I hadn’t seen elsewhere. Even its set-up—a man in a suit, an enigmatic woman, and a melancholic fantasy world entwined with a modern domestic space—is reminiscent of Jonathan Blow’s Braid (2008), a game that since its release has become a staple in discussions about how games and literature intersect.

My initial skepticism about the game faded as I spent more time with it and considered more closely its use of player perspective. Pavilion’s creators have called the game “a fourth-person adventure.” Instead of controlling the game’s protagonist directly, the player manipulates objects in the environment—sliding platforms, ringing bells, turning lights on and off—to spur the protagonist on his way. This perspective keeps the player at a distance, essentially turning her into a textual arranger, toying with the pieces of the game like a writer constructing a sentence.

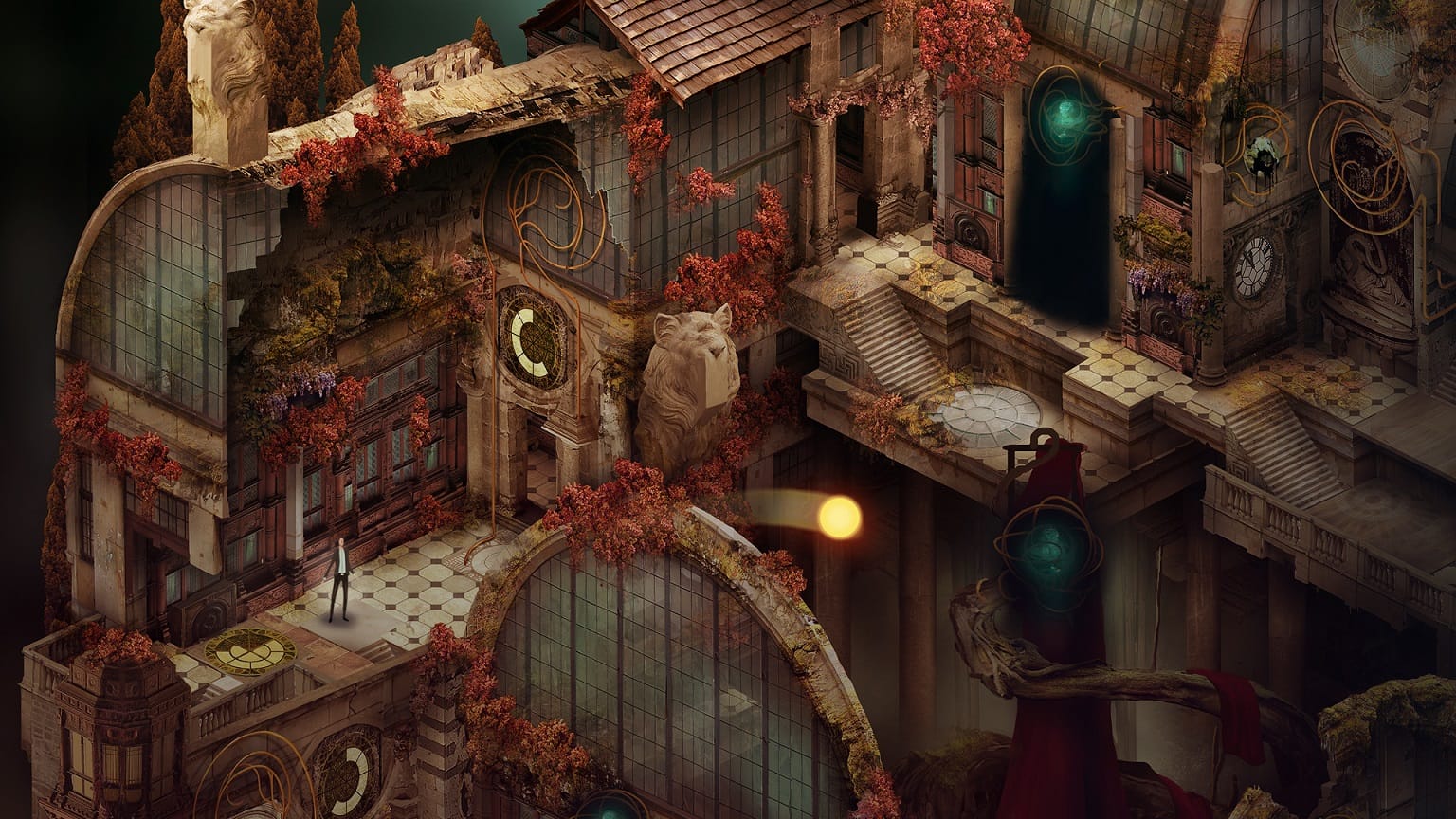

That’s why I thought of Borges and my first experiences with his prose. As I played Pavilion, building and discovering sentences through the ornate pathways of the game, I started to see parallels. The protagonist’s fixation on the furtive woman always out of reach recalled the obsession-inspiring titular object of Borges’s The Zahir (1949). I thought of Ts’ui Pên’s labyrinthine novel in The Garden of Forking Paths (1948) as I moved Pavilion’s main character from point to point, crashing against dead ends in wooden halls and forests of stone pillars. Each stage and series of puzzles reminded me of the infinite hexagonal rooms of The Library of Babel (1941). Pavilion even alludes to games like Braid, in a similar fashion to how Borges recycles the works of Cervantes, Shakespeare, and classical and biblical literature. Somewhere amid the curious puzzles and the dreamlike neoclassical ruins painted with an art nouveau pallette, Pavilion became about the language of play.

Pavilion is a series of puzzles that become sentences

For this reason, I find game’s creators use of the phrase “fourth person” a clever one, especially when considered grammatically. The English language has no account for what the “fourth-person” would be, the closest being using the word “one” to mean a general or hypothetical perspective (e.g. “One would think that article is bordering on tedious”). The player’s perspective in Pavilion operates with similar obviative omniscience. In Pavilion, more than any other game I’ve played recently, I understood my place in relation to the text, not as player but as a writer. Pavilion is a series of puzzles that become sentences. The painted visuals and Tony Gerber’s haunting soundscape establish mood for the actors in the narrative: protagonist as subject, his actions as verb, the ambiguous goal as object. I was simply there to put it in order or to play with its syntax.

Consequently, Pavilion strikes me as a particularly Borgesian game, especially given that games seemed to be what Borges wrote. The ways in which his stories fold into one another, sentences linking back to other sentences, turn them into hypertexts legible without computers. His fictions seem like antecedents to what Pavilion hopes to accomplish through its fourth-person perspective. The attentive player, like Borges’s attentive reader, uses the power afforded from a removed perspective to engage in the processes of artistic creation by showing us that each frame, each sentence is built through a number of parts to be arranged rather than a puzzle to be solved.

To that end, Pavilion’s classification as a puzzle game in the traditional sense is suspect, if not outright boring. I would hesitate to play Pavilion for its puzzles, which are not that complex, the same way I would not read Borges’ works for their plot or characters. Instead, I will likely return to Pavilion to get lost in its digital labyrinths, to discover how objects can be rearranged to play with the narrative of a faceless man in a suit. When I return to Pavilion’s twisty little passages in Chapter 2 next year, I hope recall that feeling of blissful disorientation I felt in the dizzying corridors of Borges’ prose.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.