How The Perfect Woman answers Wikipedia’s male bias

As we saw with last week’s Wikigate, a lot can go wrong when sticking people into categories. When author Amanda Filipacchi discovered that many women authors, including herself, had been segregated from the boys, ghettoized into a far less-travelled subcategory of American women novelists, she called a spade a spade. She wrote for the Times that the ubiquitous online encyclopedia is being sexist. That sparked a fiery and much need debate about the role of representation, even in publically-controlled domains like Wikpedia.

More importantly, the fiasco does illustrate the downside to our capacity to broadly generalize. Categories can bend us the wrong way, especially when they’re based on gender.

This is a truth The Perfect Woman proves beautifully, hilariously, and literally. A physical game that will have you flexing and contorting in front of a Kinect camera, the lighthearted party title by Lea Schönfelder and Peter Lu, due this October, challenges you to fit into the rigid shapes of both traditional and nontraditional roles for women. Speaking to Indiegames, Lea said the game is intended to comment on how society has created the ideal of a perfect woman, i.e. your beauty queens, knitting grannies, and Disney princesses.

Lea’s descriptions are far more entertaining than my own. She tells me the princess can command dolphins with a magic wand, but you’ll have an easier time performing the poses if you choose to become a street kid leading a gang, or one of twelve kids in a patchwork family.

Society has created the ideal of a perfect woman.

From there, the roles proliferate, as the moves you make in daycare influence whether you grow up to be “a punk girl who plays in a band in the woods, or the girl in high school that everyone wants to have sex with,” she says. Depending on how you play your cards, you can graduate to be a MIT professor, a suicide bomber, or an Oktoberfest bartender who drinks her youth away, just to name a few possibilities.

The goal is not necessarily to be a successful woman, per se. “If you want to be perfect all the time, you’ll get really hard poses, like standing on your head,” Lea says. And if you can’t pull them off, your character will die before her time. So being perfect at every step isn’t going to work. The goal is to live until the venerated age of eighty, and you’ll have to make some concessions along the way.

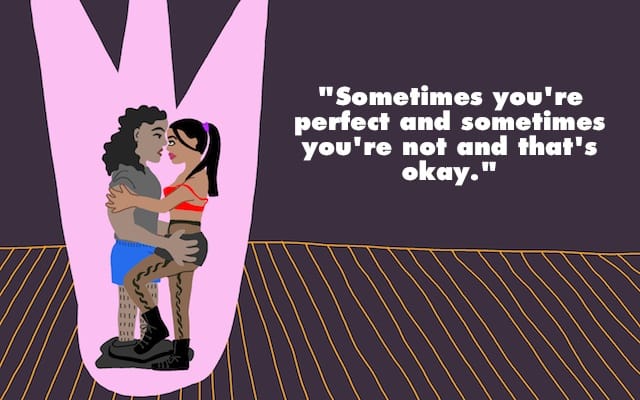

The game has a simplistic yet elegant lesson for girls, or for anyone, at its core. “Don’t be perfect all the time,” she advises. “Sometimes you’re perfect and sometimes you’re not and that’s totally okay.”

Those familiar with Schönfelder’s previous games will gladly recognize The Perfect Woman’s blemishes. Lea is an illustrator by day, her games are drawn by hand, and her style is inimitable, a completely charming array of squiggly lines and dimensionless color that’s almost childlike in presentation.

You play as a promiscuous bride-to-be who is trying to screw as many guys as possible, including a yogi, a welfare recipient, and, yes, Che Guevara.

Not to mention, her characters are uniquely incorrigible, a sigh of relief in a medium saturated with archetypal good guys and villains. In her previous game Ute, you play as a promiscuous bride-to-be who is trying to screw as many guys as possible, including a yogi, a welfare recipient, and, yes, Che Guevara. Another of her games, Ulitsa Dimitrova, sees you as a chain-smoking, Mercedes-vandalizing street urchin, all sketched loosely in blue ink.

Whereas Ulitsa Dimitrova was inspired by the disparity between the august cathedrals of Saint Petersburg and the homeless children in its streets, the idea for The Perfect Woman sprung from something less demoralizing, the throwaway personality tests found in the pages of women’s magazines. These “pseudo-psychological” quizzes, as Lea calls them, which were first dreamt up by none other than the long-winded French author Marcel Proust, were a good fit. “It was about a similar topic. All of them are about what kind of lover are you, how romantic are you, what is your life going to be when your older,” she says.

The silly contrivances of personality tests are something both of the game’s authors know well. “I read them a lot as a child at the hair stylist.” Lea tells me. “I always read the results in advance and made my answers according to what result I’d like to have, which was always the coolest one.”

“My mother expected me to be perfect.”

Peter, who’s doing most of the game’s programming and gameplay, conveys a more emasculating experience. “My older sister would always make me take those tests,” he says, “or some mean girl trying to bully me would make me take them. I’d always end up with the most embarrassing results. My first experience with indignation.”

Although neither Lea nor Peter are impressed by the unrealistic images of feminine perfection presented in the magazine spreads or in those personality tests, there is commonality. “Nobody’s going to answer, ‘I’m a bad person.’ They’re designed to make people feel better,” Lea says.

And what about The Perfect Woman? Isn’t that designed to make people feel better about their appearance, their personality, their position in life, and who they are? “Yes, of course! Because they don’t have to be perfect anymore,” Lea says. “My mother expected me to be perfect. I wanted to be perfect in school, and I wanted to have many friends. But there’s very much work involved. You cannot achieve it, or at least I cannot.”