Las Vegas’ new king of pinball doesn’t care what you think

Las Vegas is a city of lights, loss, flesh, and fantasy. Even the name of its main stretch–The Strip–provokes. People arrive with many goals in mind: win money, eat decadent food, marvel at near-naked bodies, shimmering and contorted. Tim Arnold arrived with a very different goal. After having opened a popular arcade in Michigan in the mid-70s, the arcade bust sent him west. He moved to Paradise, Nevada in 1990, just a mile from that clutch of casinos inhabited by fake Elvises and real addicts.

But he couldn’t leave his machines behind. Over the next decade he gathered and restored over 1000 tables, hosting ‘Fun Nights’ for locals and donating the proceeds to charity. Finally, in 2006, he opened the doors to his own kind of pleasure palace: The Pinball Hall of Fame.

From the street, the building looks like a nondescript storage facility. As it turns out this is exactly what it is: an airy warehouse filled with tables, aligned in some kind of ever-shifting order. Cruise by your local watering hole; if you’re very lucky you may find one beat-up table in the corner. Arnold’s oasis holds one-hundred fifty-two pins, from Heavy Hitter (1947) to AC/DC (2011).

But the Hall is more than a repository for facile amusements. It represents an old way of thinking, a no-frills dedication to wonderful machines, physical artifacts, that simply work. With so many of our entertainments shrunk down, set behind glass and stuffed in our pockets, to stand in front of a hulking device such as a pinball table is to be transported to a time when your immediate surroundings were all that mattered. The globe was a series of localities, not yet connected by invisible waves. We needed a jolt of grandeur, and we got it from wood, metal, and wires.

Arnold is the inverse of P.T. Barnum: all grit and no show. In an age when gadgets are advertised with dance recitals, Arnold and his machines come off as a place stuck in the glorious past, some rare temple untouched by modernity and its fatuous excess.

To stand in front of a pinball table is to be transported to a time when your immediate surroundings were all that mattered

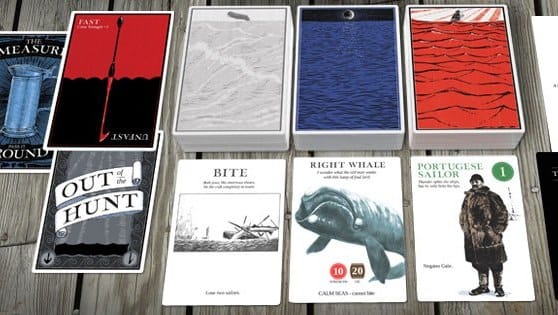

The feeling hits hardest while walking down the aisle of electro-mechanicals, tables like Aquarius and Captain Fantastic, from the 1960s and 70s. You’ll find no silicon chips here: all action and sound comes from a confluence of earthly materials and physics. Starting in 1977, tables began to use solid-state components, meaning a small CPU ran the board, creating digial audio and more complex scoring algorithms. Classics like William’s Pinbot and Gorgar talked to the players using digitized clips. Then came dot-matrix displays, animated figures like Funhouse’s Rudy, and holograms. Walk through the Hall of Fame and play fifty years of history, all for fifty cents a pop.

He is technically retired, but Arnold spends his days overseeing his machines, uninterested in common pursuits of the post-employed. “I don’t understand golf. Little babies play games with plastic balls. Real men play with steel balls.”

Arnold’s grey hair hangs in a ponytail down his back. Coke-bottle glasses and a headlamp give him the appearance of a near-blind spelunker, or some mad genius tucked away in the desert capable of reckless, dangerous things. Stories from the old days confirm my suspicion.

“Punched a woman in the face once,” he tells me. She punched him first, you see, as if that was an excuse. Arnold redoubles and explains his philosophy: “You take a stab at me? Fuck you. All bets are off.” What appears at first like graceless etiquette reveals itself as the instinct necessary for a life amongst the tables: react too slowly and the ball drains. Games today hold your hand and give you false rewards for “achievements.” In the arcade of yesterday, there was, ahem, no quarter given.

Arnold’s a lifer; there will be no going AWOL, even as the industry crumbles around him. For an operator who maintains kid-friendly playthings and gives his profits away to the local Salvation Army, Arnold inhabits the role of hard-scrabble curmudgeon well. Forty years of the same thing will do that, I guess. He acquired his first table in 1972: Gottlieb’s Mayfair, its playfield beset with top-hatted gentlemen and ladies in spring dresses. Today, he’s still investing time and money in buying new tables and keeping old ones working. The work takes a toll.

“I’m kinda sick of the whole thing. Sick of fixin’ ‘em. Sick of being here.” The dark building flashes and wails; steel balls launch against rattling bumpers again and again, an endless metallic caterwaul. There’s no end to the noise. To work amongst the tables is much like trying to master one: There is no win-state. Your score goes higher, but eventually you lose. “I’m here a lot.”

At least the present clientele are less direct in their criticism. Regulars at his original arcade back in Michigan were often drunk college kids. One day he found a dead cat’s head left on top of a Robotron 2084 cabinet. (It’s a hard game, but still.) He and his partner found ways to fight back.

“I don’t understand golf. Little babies play games with plastic balls. Real men play with steel balls.”

Arnold lives out his retirement in the shadow of Las Vegas, a town brimming with oddities and mayhem that to this pinball man seem calculated and dull. He’s skeptical of a full-scale pinball renaissance, a return to the golden era when hair metal screamed over the stereo and every town had a local arcade filled with machines. Not enough people are left who know how to keep ‘em running. Fire codes mean you can’t pack enough games into the real estate to make a profit.

And don’t get him started on digital recreations from Zen Studios or Farsight: “Have you ever kissed your sister? It’s the same thing. You can do it, but what’s the point?” As a diversion, video pinball is a lark. But there’s no replacement for the real deal: the full-body experience of standing over the glass, nudging the heavy machine for an extra inch of movement on a cascading ball, that whip-crack echoing through the air after a successful Replay high score with the ultimate reward: another game.

For many in this town, the point is to win. Pinball, by its nature, is a losing affair. Placed so close to the ultimate destination for flashing lights and coins, I had to ask: Why come here if dozens of casinos are a mile down the road?

“Because this is fun,” Arnold says immediately. “Because this involves skill. That stuff on the strip is anti-skill. I don’t know why anyone would play a game where you can’t influence the outcome.”

Here, a return investment from your quarters comes only in pure amusement, the challenge of holding onto a multi-ball run, racking up jackpots in name and score only.

Sometimes the joy comes from the discovery itself. One machine, Pinball Circus, was an experimental prototype built in 1993. Instead of the standard “table” format, Circus was built in a typical upright arcade cabinet, emphasizing vertical play using ramps and clever animatronics (hit one target and an elephant’s trunk picks up your ball, placing it on the level above). Only two machines were ever built. Full-scale production was ready to go.

But the test machine in Chicago failed to produce results better than the popular, much cheaper tables of the day. Williams nixed the project and stuck the games in a warehouse, eventually quitting the business to focus on a more profitable venture: slot-machines. Pinball Circus had become something of an urban legend; fans had seen pictures and heard stories but never played it. The Hall of Fame is the one place in the world where you can do just that.

So if you ever find yourself near Paradise, Nevada with a few extra quarters jangling in your pocket, look for the big yellow banner. Tim Arnold will be there, working while others are playing. “This product can’t be fit down a digital pipe, like movies or music or any of that,” he reminds me. “You have to physically come here.” At a time of such global reach and instant news, the limitation feels like a blessing. Just don’t tell Arnold I said so.