It’s a no-brainer that architecture has inspired videogames—in fact the quest for “realism” in three-dimensional space has been a driving force in the technological advancement of gaming. The New Aesthetic, an artistic exploration of the line between digital and actual, was solidified in pop consciousness with a dedicated panel at the 2012 SXSW Interactive Festival. Pixelation is a hallmark, though the New Aesthetic remains a bit nebulous. The term applies equally to QR codes placed in high-fashion ads, to Tetris-like installations of water in real-space on the streets of SoHo, and to the psychedelic colors captured on moving objects by Google satellite.

And what about videogames inspiring architecture? Architecture has always been a reflection of the world around us, both functionally and aesthetically, but a building’s form does not merely follow its function. The two forces in fact work synergistically. Modernism has long been misunderstood to be simply about the honest expression of materials (read: ugly)—as argued by architect Cesar Pelli, “Modernity is not defined by specific materials or aesthetic qualities but rather, the ‘authentic expression of contemporary construction.'”

In light of this theoretical idea, I think it’s odd that the New Aesthetic has focused on pixelation, when if anything, the trajectory of technological advancement has been about the reduction of pixelation. Here is just a sampling of the plethora of buildings that have captivated us:

The Cloud residential towers by MVRDV in Seoul, Korea

These towers have unsurprisingly been lambasted as insensitive to 9/11 and the former World Trade Center towers. Nevertheless, the name probably references both the outgrowth of building blocks connecting the two buildings and to cloud storage—in this case, the storage of people. The rendering has a distinctly sci-fi aesthetic, quite unlike the usual light and airy drawings preferred by architects.

The Cross # Tower by BIG in Seoul, Korea

Like the Cloud, this “Hashtag” development highlights a comeback for the skybridge trend: once a remnant of architectural theory and bad office design in the 1970s and ’80s, this time returning on a grand scale. The Atlantic Cities writes, “The “typology”, whereby Manhattan ‘skybridges’ are aggrandized to the scale of monumental infrastructure, large enough to contain a variety of spatial orders, has long existed in the imagination of 20th century architects, but has been manifested in only a handful of built structures.”

Telehouse West Data Centre by YRM Architects (now part of RMJM) in the London Docklands

Although the most mundane, I think the Telehouse West Data Centre is the most “honest” of all the buildings shown here. It’s a data center for Telehouse, an IT company, that contains complex heating and cooling systems and generators. The technical needs for this building were significant, so much so that building construction required the efforts of AECOM, the engineering firm ranked No. 1 in the world in terms of revenue from design projects.

Proposal by zarch collaboratives for Singapore World Expo 2010 (finalist)

If actually constructed, this building would have comprised 3,866 modular cubes, reflecting what at the time was the epitome of modernity. Unlike some other buildings featured here, which have overt claims to technological references, this project was promulgated as “an open model designed to continually evolve and receive wisdom from others even as we share our own experiences.” Hmm.

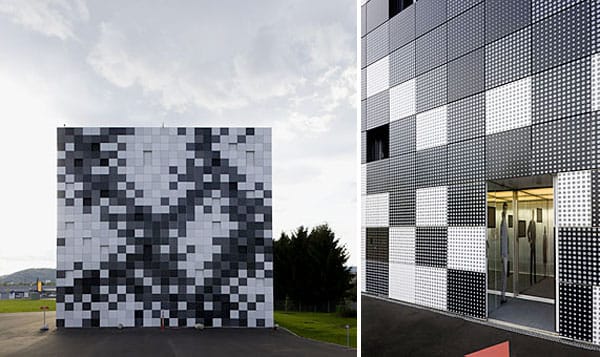

Headquarters of PRISMA Engineering by SPLITTERWERK in Graz, Austria

The building requirements for the headquarters of PRISMA Engineering were to protect the secret, proprietary technology being developed, and to have a place to perform high-end testing on the mechanical and motor products designed by the firm. The pixelation seems to be just an aesthetic choice, reflecting perhaps a desire to appear forward-thinking rather than to embody the core work of the firm.

The plethora of pixelated buildings begs the question: Is there something going on theoretically besides superficial façade tricks? Ironically, Cross # Tower, the building most obviously trying to benefit from the social-media takeover of the world, at least uses form to enable function. Public green space and community functions are built into the tops of the horizontal bars, which the architects hope will bring residents together within the structure.

For the most part, however, I think the designs of most pixelated buildings are not rooted deeply in theory. Aesthetically, they’re pretty irresistible because they make a clear visual impact and they reference forms from a prior technological period that are easily recognizable by societies that collectively lived through it. But many of these buildings are being designed by large architecture conglomerate firms—not by star architects or smaller boutique firms, but by the nameless faces behind MRDRV, RMJM, BIG, and other acronyms. Perhaps these syndicate-style corporations are the real extension from videogaming to architecture, designing inscrutable pixel buildings as space invaders.

For the future of our cities, I hope we can collectively move beyond pixelation as both designers and consumers, and incorporate more of what gaming and technology has to offer in the real world. Architecture is in a strange place. Designers like Zaha Hadid are doing aesthetically similar mega projects in whichever city is hailed as the latest emerging one; Frank Gehry is criticized for losing his grit; and large corporate architecture firms have taken over, levying generic glass towers on our cities regardless of local conditions, and the occasional pixelated megastructure to confuse us out of complacency. I think we’re all already asking, what’s next?

Block Quotes covers the architecture of videogames and their relationship with the real world (and vice-versa).