Placing faith in The Last Cargo’s atheist allegory

If videogames are to be believed, religious indoctrination is a simple process. Give them some sandals, candles, and maybe a sacrificial altar or two, and apparently, people will gladly pledge their lives to an unseen power. From the Unitologists of Dead Space to the Mythic Dawn of The Elder Scrolls, religious devotees and cult members alike are seen as little more than victims of themselves; brimming with an innate violence, and led to enact evil if just because they are.

Needless to say, it’s a naive depiction, but it works. Traditionally, videogames need bad guys; a role that the indoctrinated are more than happy to fulfil. Unquestioning and unquestionable, they have become one of the medium’s bread-and-butter sources of cannon fodder. They are easily identifiable—just look for the guy chanting in Latin—and even easier to kill: the hard realities of the people underneath declared moot in favour of squishy things to shoot.

Two-man indie developer Ehnenu, however, is hoping to offer a different take. Their upcoming survival horror The Last Cargo is going to place its player in the mind of “a man exposed to the debilitating power of religious indoctrination,” in an attempt to depict the unpleasant realities of religious dogma.

“The idea for The Last Cargo was the result of a simple observation of our surroundings,” Ehnenu’s Paul Kulikowski told us. In his native Poland, 86.7% of the country belongs to the Catholic Church, with only 2% declared atheist. Along with his brother Daniel, Paul is hoping to demonstrate what it’s like “to be an atheist in a world full of countless beliefs.”

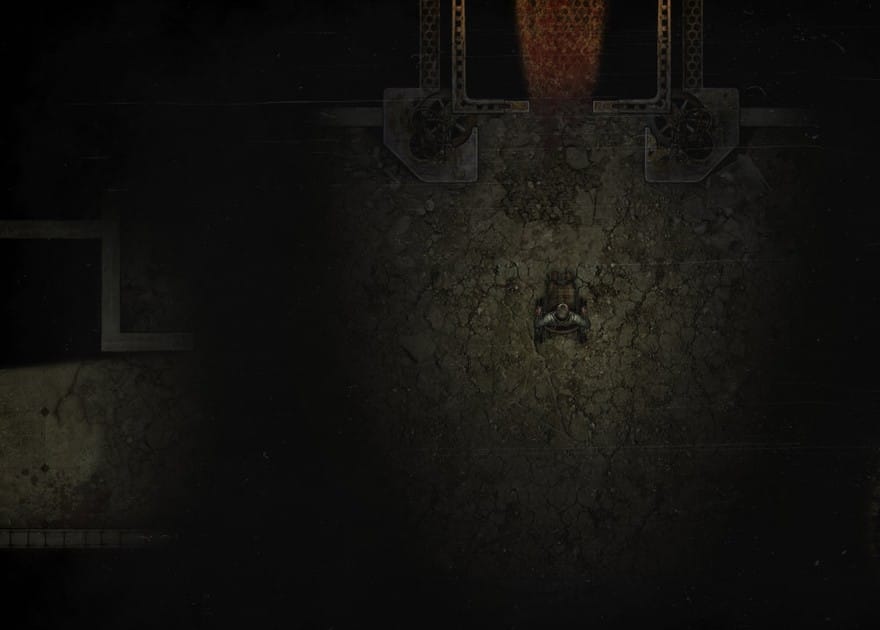

The Last Cargo is an empathic exercise that wears its allegory on its sleeve. The player character has been bound to a wheelchair—“his beliefs, imposed onto him, have limited his movement”—while his surrounding horrors clearly evoke religious iconography. The Last Cargo is unashamedly loaded with symbolism, Kulikowski keen to make clear that nothing in his game was chosen “by accident.”

The idea of “cargo”—of misguided aspiration—has become a key term in the understanding of cult practices.

This, of course, includes the title. “The Last Cargo” refers to the cargo cults of Melanesia, the Pacific islanders who would imitate US soldier behaviour in the belief that it was some benevolent god, and not cargo planes, that would routinely make supply drops onto their islands. The idea of “cargo”—of misguided aspiration—has become a key term in the understanding of cult practices, and one that Kulikowski is keen to explore as a metaphor for Western systems of belief.

He cites Richard Dawkins’ 2006 polemic The God Delusion as an eye opener. It “showed us the size and seriousness of this problem,” he said, stressing that the game shouldn’t be confined to its anti-Catholic origins. “Initially we wanted to focus on specific religions and relate to their symbols, but we realised that indoctrination is more a relationship between people than a religion or cult,” he said. “We want to go one step further and try to address the psychological substrate of indoctrination.”

The survival horror genre is, of course, no stranger to psychological substrata. Yet The Last Cargo isn’t dealing with ethical absolutes. Silent Hill’s demon-worship and Resident Evil’s parasitic mind control are both clean-cut evils, replaced here with the wider grey expanse of belief itself. If it doesn’t tread carefully, The Last Cargo runs the risk of becoming the very thing it seeks to expose; trading one set of sandals for another.

“It’s a very hard topic for a game, especially for an independent game with limited resources,” Kulikowski admits. “But we’re aware of these difficulties.” The brothers are eager to emphasise rationale over atheism: The Last Cargo doesn’t want to tell people how to think, but rather just encourage them to think in the first place. “Our biggest challenge,” Paul says, “is to try to expose (the) vast forces of irrationality, and demonstrate that the line between common sense and insanity can be very thin.”

The Last Cargo won’t be for everyone, clearly. Although the brothers believe that “every single one of us, to a greater or lesser extent,” has fallen foul of indoctrination, they acknowledge that some of the game’s messaging will “depend on the player’s perceptiveness and sensitivity,” both to the game world and the issues at hand. For those who it reaches, however, the Kulikowski’s messaging could prove vital. Ultimately, it all depends on the deftness of Ehnenu’s touch. The extent to which The Last Cargo either exploits or appeals to its players’ sensitivity will be the altar on which its fate is decided.