Playing War: A New World Algorithm

I am an electronically generated avatar, fueled by an imaginative lust for living beyond myself. The enemy, or the goal, waits to be destroyed, or overcome. The rules and options of this world are limited to controlled algorithms, which must be interpreted to win and proceed to accomplishment. Once the scenario is grasped, I formulate my strategy, operating by the rules of my controller, and after a period of trial and error, dominate my opponent.

Growing up, each of my siblings went in a completely opposite direction. I moved to New York to be an actor. One brother joined the military, while the other joined Bible School. My sister became a basketball star. I’d been vexed by video games—their broad storytelling is arguably why I grew attracted to brighter lights—and the journeys I’d take with Link, Cloud, and Earthworm Jim, among others. My brother, always carrying the archetype of the protector, grew distant at the sudden death of my younger cousin, no doubt feeling as if he’d failed somehow. Eventually, while I was traipsing around with the theater, he decided to join the Army.

At the young age when one might subscribe to be a gamer, the mind is ready to be shaped and evolve within the environment, easily susceptible to a persuasion occurring on and off the digital screen.

The in-game avatar is the perfect soldier; he doesn’t ask questions, or think outside the specific box that is given to him.

My brother and I were no strangers to this virtual seduction. The in-game avatar is the perfect soldier; he doesn’t ask questions, or think outside the specific box that is given to him. He is confined to a set of tasks and obligations. The American Military, understanding this, is unparalleled in complexity and strength. According to my brother, saying that you “choose your own adventure” is considered slander.

While he was already quiet and reserved, his visits home from being on tour were stifling and awkward. He’d grown physically bigger, a sense of entitlement upon his shoulders, flaunting an applied importance in his environment. With us in his jeep, he’d go ninety down back roads as if he was still careening through a No Man’s Land.

I thought about the potential loss of his humanity. It is far from me to cast judgment upon anyone in the military—there are simplicities I have chosen in my lifestyle that stay degrees removed than those called to war—but I increasingly felt ill about the prospect.

In the past century, war has grown beyond being the world’s biggest export; the blood shed on a battlefield pulses throughout the life force of the global economy. Hideo Kojima, in Metal Gear Solid 4: Guns of the Patriots, states:

War has changed. It’s no longer about nations, ideologies, or ethnicity. It’s an endless series of proxy battles fought by mercenaries and machines. War—and its consumption of life—has become a well-oiled machine.

I saw the hero inside my brother. The Army saw it too, casting him as a protector; he was rewarded and glamorized. They asked him to step forward and fight for our country’s freedom; to commit to a collective force greater than the individual. It spoke to the psychological need within all of us to simply belong.

There’s more than one opportunity to answer this call. One can live the experience through the increasingly realistic scenarios of Call of Duty: Modern Warfare, Call of Duty: Black Ops, Halo, Medal of Honor, Killzone, and more. During a video review of Modern Warfare, a critic remarks that certain homing HUDs looks exactly like they do in real life. Some of these games are notably fantastic, though do they inspire—through the military’s genius mass-marketing strategies—children faced with extreme social and emotional oppression to escape from their worlds into the nurturing arms of Uncle Sam? Certainly it is not unheard of for the military to fund the development of these games, or to use them as a part of recruitment or even early training strategies.

The films War Games and Toys have both explored scenarios where gaming and computers might unwittingly take over the realm of warfare. On screen, there is no emotional response in what developers call the “uncanny valley”—the more alien and fake something created looks, the more detached we feel from them. In Halo, one mounts an assault upon the alien Covenant: monsters and demons to our eyes. The same could be said about Tolkien’s orcs and classic Disney villains. These are the demonic “others,” a force against which morality need not apply.

Through the impact of this separation, soldiers are allowed to forget the people they may be killing, and instead target aliens, zombies, demons, or any other entity prescribed as an enemy combatant, as determined by the corporate or political interests behind the military force. Further, strictly corporate armies are no longer a myth of science fiction.

Our enemies look like us. I feel it is cowardice to run away from the pain of murder. I am far from understanding the consequence of war, and knowing the trauma my brother felt overseas. Circumstances aside, I recognize the emotional conflict it caused between us. We bottle up, contain, and fester natural discord until eventually we purge, somehow, with violent release. The taboo of murder is suspended in the context of war, religion, or justice. It has always been thus, and maintains an intimate relationship with the psychology of martyred sacrifice.

Strictly corporate armies are no longer a myth of science fiction.

To keep these emotions at bay, under various consequences, we turn to the soft suppression provided by technology. Ray Bradbury’s sleepwalking society of Fahrenheit 451 places tiny bugs in their ears to play music. They surround themselves with walls of television screens. David Whyte, an acclaimed international poet, implies that we encircle ourselves with distractions—radio, television, pop culture, the Internet—to keep ourselves from turning inward and facing our darkness and pain. (Though media can also help guide us through such darkness).

Seeking clarity, I offered a draft of my ideas to my brother, who was since removed from the frontlines and stationed in Colorado Springs’ Fort Carson. I wrote, “To be fair, if there’s anything you feel is wrong, please communicate that to me.” Eagerly awaiting his response, and his respect, I received his reply about a month later.

Sentences scrambled together, though admittedly well-thought out, he quoted Aristotle and even Tennyson, attacking the notion of being “anti-war” while not addressing my questions, using the flame to ignite his retribution. It often and unfortunately read like a fascist manifesto, capitalizing words like “Soldier” and, in reference to America, “She.”

There was little evidence of a person left, only aspects of a computer algorithm forced to repeatedly digest and excrete one highly propagandized perspective. He confirmed his “lust for living beyond himself,” a quality we both share, and openly confessed that, regarding my questions, “…none wish to believe they have been wrong for so long.”

The desire to keep freedom alive and our country’s “divine right” to primacy arguably justified his martyred hero. He subjected to the violent authority that dictates military strategy, driven home with his own words, “deploy, engage, and destroy.” This is the voice that ensures our enduring heaven on earth. My brother was only confirming my fears.

A powerful monologue from Michael DiMartino and Bryan Konietzko’s Avatar: The Last Airbender showcases the character’s discord with the ideology of his country, a cancerous patriotism:

Growing up, we were taught that the Fire Nation was the greatest civilization in history. And somehow the war was our way of sharing our greatness with the rest of the world. What an amazing lie that was. The people of the world are terrified by the Fire Nation. They don’t see our greatness, they hate us. And we deserve it. We have created an era of fear in the world. If we don’t want the world to destroy itself, we need to replace it with an era of kindness and peace.

In an article titled “Barack Obama: Papa in Chief,” Tom Junod describes a speech where the President announced sending troops to war without playing the conventional “evil card,” leading to a less-than-enthusiastic response. Ironically, when he accepted the Nobel Peace Prize, he defended war, this time proclaiming, “Evil does exist.” Junod comments that it was “… clearly something he felt he had to say because he didn’t quite make the sale in his earlier speech. In the end, it’s awfully hard to make the case for war without making the case for evil.” In my opinion, that’s all the more reason not to make the case. If the President needs help selling war, he should talk to the folks at Activision.

With the effect of a repressive emotional response, media can both inspire and suffocate our imagination; incubating, among other things, better soldiers and worse human beings. The world of video games, although continually more interactive, fun, and entertaining, is currently limited, barely aware of the mind’s psychedelic potential. As we grow up in our exciting new world, more and more science fiction becomes reality; mythology glides into co-existence with the technological age, and we are imbued with a heroic responsibility to shape the world into “an era of kindness and peace.”

The world of video games is currently limited, barely aware of the mind’s psychedelic potential.

Two years after the letter was sent, my brother and I made peace with each other. He’d long been out of active duty, and we were both able to acknowledge the extremities of our perspectives, and the truth of where we belonged in the world. Our past correspondence allowed for that primal purging of emotions to be met, on both our parts, as unresolved as it seemed. And I honor him.

Video games have become more significant and powerful with each passing year, amplifying themselves as the newest mass mythic expression of our culture. If comic book heroes and celebrities are mirrors for gods, then video games’ immersive storytelling experiences allow for vivid reenactments of such new and classic unconscious journeys.

Developers and storytellers of all kinds have a responsibility to cast healthy, progressive imagery into the hearts and minds of the current generation. They challenge us with the darkness, and use entertainment as a tool for learning; play is a key learning tool. But sometimes their efforts become sculpted entirely by the synthetic desire of consumerism. Infinity Ward’s epic war franchise hits too close to home, feeding wartime propaganda instead of challenging it. Even after trained soldiers experience the aftermath of a bloody battle, no world is real anymore, and the victims wander, caught between the shell of the military and the core of their souls, buried under layers of cast-iron conditioning.

My avatar is now a fully realized impression of myself, the whole human being, and I explore virtual space as freely and openly as I do my own world, aware of the boundaries, and aware of their ability to be surpassed. I find clarity in forming my own vision, with the rules of my choosing, where all myths might exist in harmony. No obstacle is finite. No dream untold. The universe is my new game.

A version of this article originally appeared on The Immanence of Myth anthology, published by Weaponized.

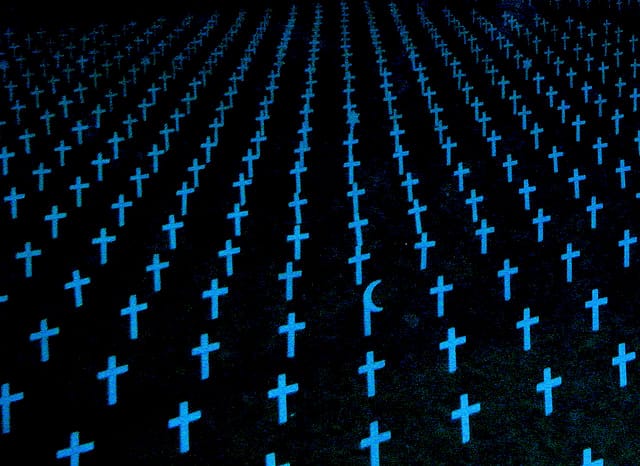

Header image via kevin dooley

Middle image via Marine Corps Archives & Special Collections

Bottom image via psygeist