Playing with touchtone phones and old TV sets at the Experimental Gameplay Workshop

It was an early afternoon on the final day of the Game Developer’s Conference this year. Everyone scuttled into one of the larger panel halls of the Moscone Center, most looking exhausted over one of their busiest weeks of the year (or maybe just hungover). As everyone swiftly got seated, the panel hall buzzed with anticipation for the 14th annual Experimental Gameplay Workshop. Curated by Funomena’s Robin Hunicke and independent game designer Daniel Benmergui, the Experimental Gameplay Workshop celebrates the best of the weirdest innovations of what it means to play. This year’s workshop celebrated 16 games, cherry-picked from nearly 200 submissions, about everything from slapping your friends with My Little Pony-esque hats, swipeable B-Boy emulators, to even simulating the poetic, transcendent mindset of a classic philosopher’s novel.

After the resurgence of a familiar title, the second game showcased of the afternoon was Operator, created by Travis Chen and Peter Javidpour. Operator’s premise is straightforward. You, the player, are a technician of an orbital satellite, aimed directly at Earth. “You don’t know what you’re doing,” summed up Chen succinctly. Luckily you have access to your company’s customer service support line. That’s where the game really comes in. Chen and Javidpour created an interactive tool out of an old touchtone phone, which the player actually uses to dial the support line for help. In a nutshell, as described by Chen, Operator “celebrates the joys of automated customer support systems,” or rather, the immense frustration that comes from them. The original prototype for Operator wasn’t created initially with as much touchtone phone-filled fun, but instead had a voiceover within the game. “[But] it just didn’t bring back those frustrating memories,” said Chen. For Operator, the game was initially planned to be a long “epic” experience, before Chen and Javidpour realized that 10 minutes was the “sweet spot” for fun frustration. And thus, the shortened, touchtone phone-controlled Operator was conceived.

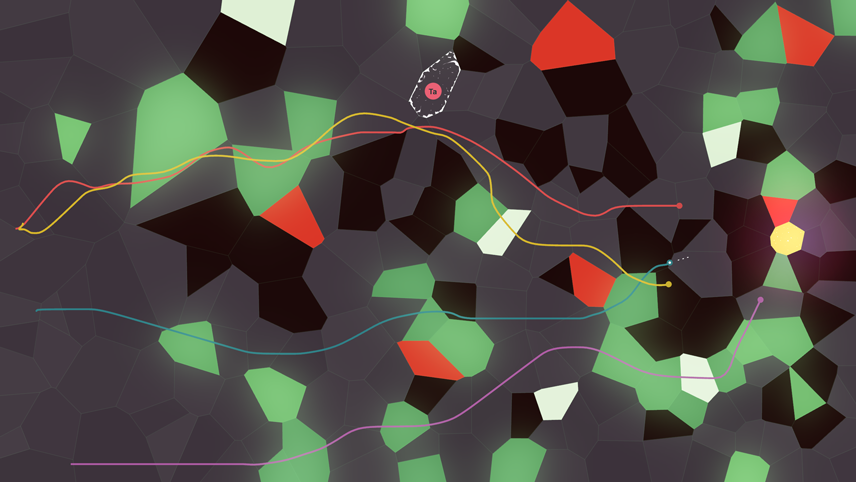

When the word “esport” is dropped, the descriptor “casual” is usually not alongside it. Fortunately, that’s not the case for Tomasz Kaye and Richard Boeser’s “casual esport” game Chalo Chalo. Described by Boeser himself as a “a very slow racing game,” Chalo Chalo is a procedurally generated competitive game for up to eight players at a time. Each player is a different colored dot, racing at the speed of a snail towards a yellow cell on the opposite end of the map. Different areas of the map are color-coded. Black areas make the player move extremely slow, red kills the player instantly, and so on. Reaching the goal first nets the player two points, second place gets one, everyone else zero, but if they die, the player loses a point. For Chalo Chalo’s live demo, the panel hall transformed into a mob of spectators; yelling, booing, and cheering at the cusp of the goal for every match. And honestly, that’s at least half of what esports are all about: gettin’ hyped in a crowd.

“This is why I make games”

Later in the event emerged Jerry Belich and Victor Thompson with a modified 1951 Capehart television set, embodied with various knobs, smackable sides, and adjustable antennas. As the player twists knobs and adjusts the antenna, or bats the side of the television, they solve puzzles on the screen at a given time. Such as: screen’s a bit fuzzy? Adjust the antenna to get a better signal. The game itself, Please Stand By, in this way lies in a similar realm as Operator: both set to portray the deep rooted feeling of frustration when dealing with arbitrary technology. However, Please Stand By hopes to step deeper beyond just its alternative controller’s presence. In the 1950s, technology was ever changing. Radio was a thing of the past. Communism was everywhere. Broadcasts were the source of any and all news. In an updated, longer version of Please Stand By, Belich noted that they want to explore the idea of what if all the broadcasts ended, what would happen? How would people consume information and news? Or as Belich chillingly said, “What happens when there’s no information left?”

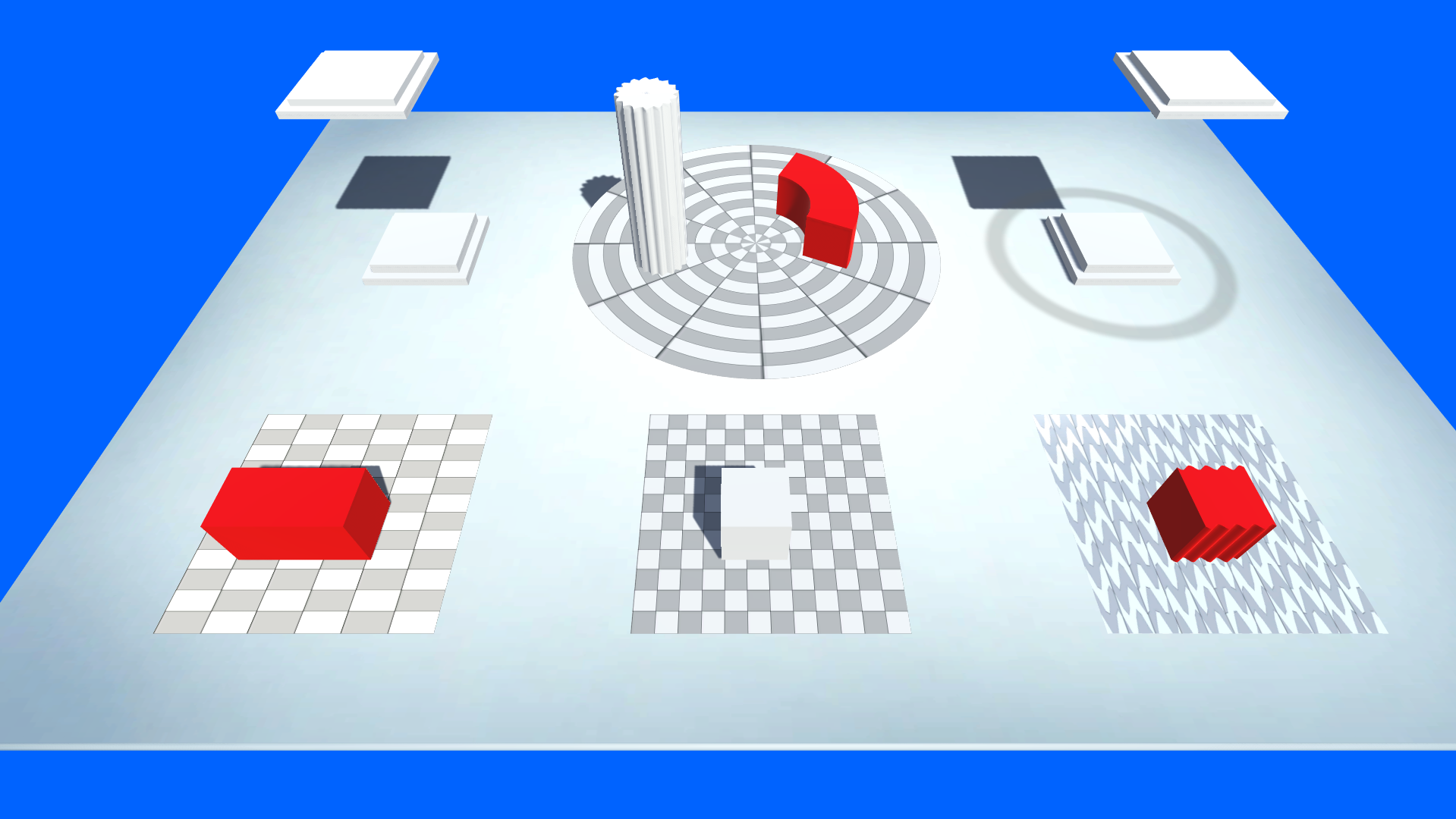

The Experimental Gameplay Workshop amplified its celebration of creativity once more this year. The sheer breadth of different aspects of play being explored by game makers was awe-inspiring, whether with creative alternative controllers to enhance the experience, or just looking at the ways we play within games in a fresh, new way. Perhaps the show-stopper of the afternoon was Iranian game designer Mahdi Bahrami’s latest experimental title, Tandis. Tandis is a bit hard to simplify into layman terms.

Inspired by Celtic shapes, the game experiments with topological transformation. Topology is the mathematical study of shapes preserved through any sort of twisting or other deformation (such as, a sphere is topologically identical to an ellipse). In Tandis, the player shifts an object between two different flat planes that actively deform the object to match its cousin (another object on the board). Tandis is most simply explained as geometry made into an interactive puzzle; making math actually kinda fun. During its live demo, Tandis’ topological mechanics created a shape that Bahrami didn’t anticipate, and to him even, it didn’t make sense. In between semi-confused laughter, Bahrami said, “This is why I make games.”

A list of all 16 games from this year’s Experimental Gameplay Workshop: Fantastic Contraption (Lindsey Jorgensen and Sarah Northway), Operator (Travis Chen and Peter Javidpour), Plosh: Time Bomb (Chris Hazard and T.C. Chang), Floor Kids (Mike Wozniewski and Jonathan Ng), Chalo Chalo (Tomasz Kaye and Richard Boeser), Simple Circles (Jeroen Wimmers), Tandis (Mahdi Bahrami), Mu Cartographer (Titouan Millet), Everything (David OReilly and Damien Difede), Orchids to Dusk (Pol Clarissou and Marskye), Walden (Tracy Fullerton), Untitled (Jason Rohrer and Thomas Bailey), Please Stand By (Jerry Belich and Victor Thompson), Let’s Robot (Jillian Ogle and Ryan Tharp), and Slap Friends (Terence Tolman and John Ceceri III).

Check out the rest of our coverage of GDC 2016 here.

This article has been edited to credit Tomasz Kaye as a developer for the game Chalo Chalo, and clarified the scoring of the same game.