Ken Levine, Bioshock’s writer and creative director, mentions Dungeons and Dragons in almost every professional interview of his life. It’s usually to paint a picture of himself as a sad little nerd-child—in an interview with CNN, he once described himself literally playing the tabletop roleplaying game alone in his family’s basement. He was the paladin; he was the orcs. He was the necromancer cackling at the top of the castle. He was the castle.

He eventually found friends to play with, but in case you found yourself envying young Levine in his basement omnipotence, Guild of Dungeoneering offers a similar experience. The game puts you in the shoes of an enterprising guildmaster looking to edge in on the thriving market of shiny things dragged out of monster caves. To this end, you send a long, long succession of adventurers doomed to die at the hands of goblins, skeletons, ghosts, and some creep named Embro who won’t stop talking about drying off post-shower. You bedeck them in items of power, such as pigeon nests and cooking pots, to stave off death a little longer. The long-term goal is to build your little meat-grinder into the best guild this side of Rohan.

dungeoneers are predictable little grubbers

Of course, like any good money-making scheme, you’re playing both sides. The dungeon is only partially complete, with a few predetermined monsters and quest-specific items already in place. Each turn, you can make the dungeon a little more friendly to your adventurer by completing pathways or placing loot-filled rats for her to squash on the way to more formidable foes. You don’t really control the meandering heroes except in combat, but dungeoneers are predictable little grubbers, and will follow breadcrumb trails of treasure until they stumble into whatever magic orb you wanted them to grab.

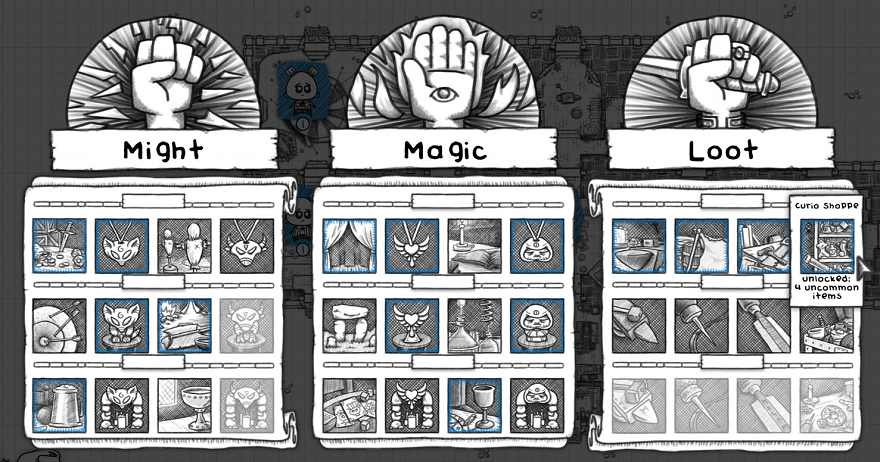

You’re ostensibly doing all this to earn gold for new rooms in your guildhouse, such as libraries to attract wizardly types or rooms full of meat for the barbarian. For being right there in the title, though, the guild-building side of the game feels like the flimsiest part. Since you’re limited to one adventurer per dungeon trip, unlocking a new class usually means abandoning your previous ones. Instead of forming a team, you’re constantly trading up for the newer, hotter model. Building tanneries and blacksmiths can unlock new items, but those show up at random in dungeons—your little employees go empty handed into the breach every time.

It would be easy to write off Guild of Dungeoneering as a single-player version of Munchkin. The jokes are essentially a second iteration of the stupidly popular card game, and the fact that they’re sung by a rhyming, lute-strumming minstrel only makes them a little better. Elements of the art style even look familiar, though Guild of Dungeoneering more directly references tabletop life with its scribbly, graphing paper backgrounds. The one place where the game escapes easy comparison is in the combat, a deck-building game with a lot more depth than I expected.

Each class starts with a unique set of cards. By kicking the shit out of goblins and fire elementals around the dungeon, your dungeoneer gains items that increase their attributes. Increasing attributes adds cards to your personal deck, and the higher you can bump up your attributes, the more powerful your new cards will be. My shapechanger, decked out in a daisy crown and fur pelt and swinging a troll femur, got all the way up to Growth 4. I was regenerating so fast, I often left battles with more health than I had going in.

Impale yourself for all I care. Plenty more where you came from.

But Guild of Dungeoneering itself, like an adventurer atop a quivering acidic Ooze monster, stands on unstable ground. Its biggest problem is also its central joke—your heroes are so utterly expendable that they can die with no consequences. Without equipment or levels carrying over, there’s no difference between your veteran Ranger and the newbie that shows up to replace her when she inevitably dies. There’s no sense of progression, no pride in your little dumb dungeoneers that won’t soon evaporate. Without continuity or risk, I got negligent in my dungeon creation. Is this dire scorpion too tough for my alchemist? Eh, whatever, I wasn’t feeling this run anyway. Go, little alchemist. Impale yourself for all I care. Plenty more where you came from.

Playing Guild of Dungeoneering is probably better than playing Dungeons and Dragons by yourself, but I suspect that playing D&D with other people is better still. The interplay of Dungeon Master and player is controlled chaos, thrilling in its unpredictability, while the outcome of Guild of Dungeoneering is a foregone conclusion: I will throw a neverending horde of adventurers at a dungeon until I complete it or get bored and wander away. Plus, in real tabletop roleplaying, you can throw beer cans at anyone who won’t stop making puns about their “cat burglar.”