PlayStation 2, the videogame console from outer space

This article is part of PS2 Week, a full week celebrating the 2000 PlayStation 2 console. To see other articles, go here.

///

What makes a videogame console successful? Forget about software libraries and units sold, I’m talking about the design of the actual box that you hook up to your TV. At first blush, the Nintendo GameCube seems pretty notable. It’s downright adorable with its purple color scheme, cute miniDVD discs, and stout, blocky profile—and let’s not forget the notorious handle on the back to be used for carrying the console around like a Playskool oil lantern. The GameCube iterates on console design aesthetics, maintaining the toy-like physicality that Nintendo had previously capitalized on with more tactile cartridge-based game formats (NES, SNES, N64)—sensibilities that they would go on to deliver exclusively through the Wii and Wii U controllers. However, while unique, the GameCube’s design symbolized Nintendo at an impasse. Like a cartoon plopped into the real world, the GameCube was endearing, but its prospects flat and impractical. On the other hand, the GameCube’s contemporary, Sony’s PlayStation 2 (PS2), not only signalled a significant market explosion in videogame console popularity, but did so by merging its technical versatility with slick, referential aesthetic conceits.

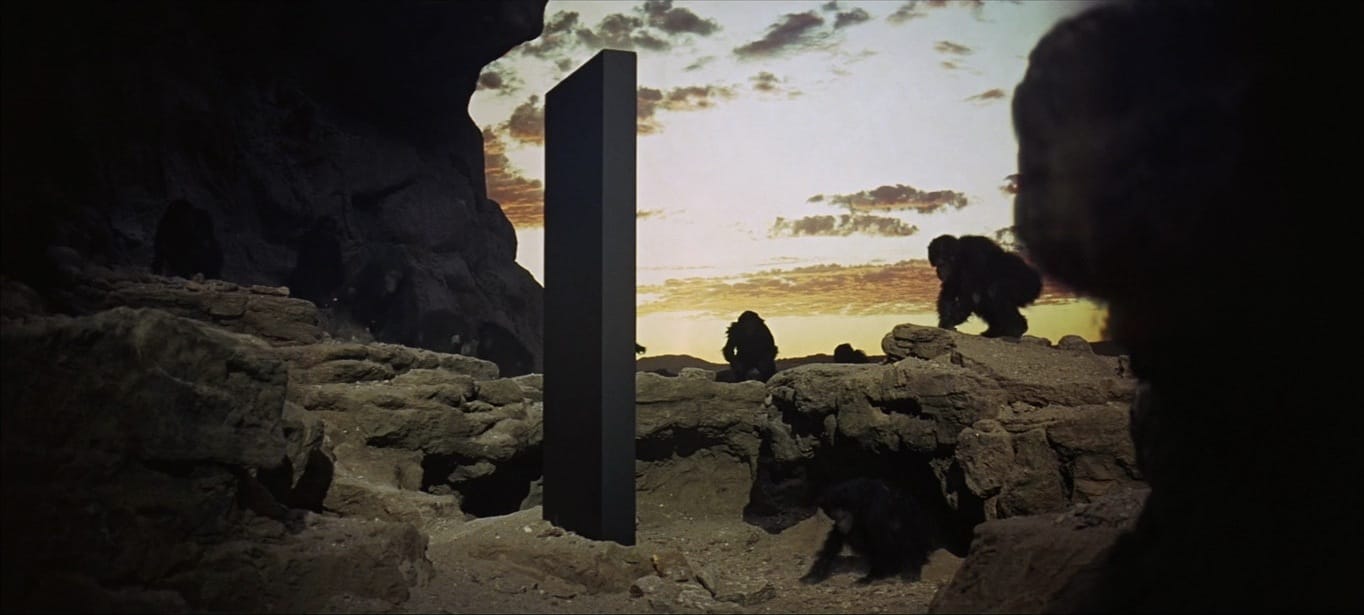

The PS2 isn’t toy-like at all, though it is the closest you’ll get to an action figure of the monolith from 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). The console comprises two thick, black rectangles (the smaller of the two acting as the base) stacked on top of one another, or if you prefer, side-by-side as the machine functions both horizontally or vertically. On the topside is a thin electric blue “PS2” logo composed of one single, non-overlapping line per letter, bending only at 90-degree angles, as if prisms were refracting a laser, and allowing negative space to do the heavy lifting. The console’s base is mostly surrounded in humming ventilation slots. The top form contains the automated disc tray, controller ports, and memory card slots, and is outlined by a stack of squared-off ridges and recesses that grant the console an architectural feel, as if each layer was a tiny balcony for gazing out upon your living room floor.

it is the closest you’ll get to an action figure of the monolith from 2001: A Space Odyssey

Functionally, the PS2 was made to be versatile. Sony used it to lead the charge for game consoles to be more than just machines that can play videogames, serving instead as all-in-one entertainment hubs. In addition to playing PS2 games, the console could play original PlayStation games, music CDs, and perhaps most importantly, DVD movies (this was the year 2000 after all). In a sense, the PS2 aspired to implement more PC-like capabilities while remaining a television-based living room device, not daring to encroach on the office desktop. As a result, the console’s appearance has more in common with a VCR, or other audiovisual boxes of the time, than it’s gray PlayStation predecessor.

While Sony master designer Teiyu Goto has had much to say about his iconic PlayStation controller design, there is far less on the record about his creative thinking behind the PS2’s aesthetic. We know that the option to situate the console vertically was partially a practical response to spatial concerns in smaller Japanese homes, but other elements had a global audience in mind. “The most difficult challenge to overcome was to give (the PS2) a design that would be popular all over the world,” Goto said in 1999. He went on to explain that the thin blue logo on the large black background was meant to symbolize our watery Earth as a small entity surrounded by the vast darkness of space. This cosmic design is meant to be literally universal in application. Perhaps the Kubrickian connotations are no mere coincidence.

It’s no secret nowadays that the shape of the PS2 is highly derived from the unreleased Atari Falcon 030 MicroBox computer. Sony even cites the Falcon in its PS2 US patent filing. Both have similar form factors and incorporate the stacked double-box design and ridged “grill” pattern, and both could be oriented vertically or horizontally. It’s ironic that Atari abandoned the Falcon line of products in 1993 to focus on the ill-fated Jaguar videogame console, only to have Sony pick up the successful design elements of the MicroBox seven years later, using it to begin steering the console industry in a more PC-like direction. Testament to this, the PS2 harbored a bunch of office desktop migrants, such as USB ports and an expansion bay for an optional hard disk drive, plus an Ethernet adapter for connecting to *gasp* the internet. These sensibilities reflect upon the console’s design itself. The possible vertical orientation of the PS2 (rotatable logo and all) isn’t mere happenstance—the PS2 was on the frontier of making people more comfortable with the physical presence of a PC tower-like structure in a leisure environment.

Another of the PS2’s steps away from toy aesthetics was toward architecture, particularly Brutalist structures referenced in cyberpunk science-fiction stories. The PS2 doesn’t just stand next to your television, it looms. The console’s ridged grill is its defining physical characteristic, and though stark and unsubtle, it’s rich with visual reference. Looking to a classic cyberpunk film like Blade Runner (1982), the PS2 would fit right in as a model for one of the dystopian Los Angeles skyscrapers. Flat, windowless, and dark; as is the perpetual night of most cyberpunk settings. The slotted ridges cut into the ground like the teeth on an excavator blade. Pivoted horizontally, they become scanlines from interlaced images projected large scale, or the slats of shadows cast through film noir windowpanes. A giant fan spins ominously on the backside, like the entrance to the anonymous Men In Black (1997) operations facility.

Flat, windowless, and dark; as is the perpetual night of most cyberpunk settings

Yet, even with this emphasis on high-minded design, the PS2’s contours are practical—the system needs to be housed in a box, and the PS2 never pretends it’s anything but a box. There’s a blunt honesty in Brutalist architecture, and the PS2 feels likewise designed around its functional necessities, much the way an office building needs its requisite elevator shafts, bathrooms, and stairwells. Despite the PS2’s harsh exterior, it’s quite user-friendly. When horizontal, its flat top allows you to stack other electronics or accessories on top of it. While the PS2 itself is a sizeable object, its shape is more akin to a modular puzzle piece than some prized totem to be gawked at or fiddled with.

And if the PS2 has a reputation for smart, practical design, the compact PS2 Slimline model is that same set of sensibilities condensed into their purest form. Maintaining most of the original PS2’s functionality, the PS2 Slim (available in silver) is like one of those solid tungsten KILO cubes, if they were cheaper and could also play videogames. Literally quarter the bulk of the fat PS2, the Slim is the size and shape of a relatively scant novel. Put as many handles on the GameCube as you want, videogame consoles don’t get more easily transportable than the PS2 Slim. On late model Slims you can even use the same power and AV output cables between PS1, 2, and 3 (PS4 went HDMI-only, but the power cord is still the same), which makes console swapping a breeze.

It’s unfortunate that the next generation of consoles (Sony’s PlayStation 3 and Microsoft’s Xbox 360) took so many design cues from the bloated Aggro Crag trophy that was the original Xbox, but they did likewise aspire to be more computer-like (or computer-lite?) entertainment hubs a la the PS2. It wasn’t until the Xbox One and particularly the PlayStation 4 debuted in 2013 that the appeal of the PS2’s design came back in vogue. The PS4 went so far as to re-adopt the blue laser color scheme and black monolith profile, tweaking the edges of the console to form a no-less-imposing parallelogram profile to match the hulking rectangle of yore. It’s worth reiterating that, though the PS2 signaled a shift for consoles away from being exclusively game machines, it did so not at the expense of its design, but as the driving focus of a universal aesthetic.