This Is The Police won’t accept blame

Content Warning: discussion of rape, violence against women, police brutality, racism.

This is the police. This is the police station. This is the police chief. The police chief is you. This is your desk. This is your scanner. It will be your Beatrice, a voice beckoning you to rise from the grime. It is the only voice in the world that begs to be silenced. But you relish it, this song from the streets. It reminds you that you still have a purpose, two-timing wife be damned; it reassures you that you are still the man they come to around here. You take comfort from the fact that it will stop singing only when you’ve stopped being able to hear it.

This is Freeburg. This is your city. You’re the most popular police chief in the history of the city, and the most morally upstanding. Everyone says so. Well, everyone except the feminists. And the black citizens of Freeburg, they also seem upset—but you, the police chief, you know that they just want attention. You always know what people want. That’s how you ended up here. It’s why you’re so good at navigating the press conferences and misconduct hearings; you understand how to redirect blame where it will hurt you least. After all, City Hall is the real problem. You’re just doing your job.

This is your city. This, right here in the middle of your office, is a model of your city. It allows you to see, in a glance, where crimes are called in and what progress your officers have made in responding to them. It’s a real headache sometimes, trying to follow it all. Sometimes you blow off calls out of sheer exhaustion. But other times, when it’s quiet on the streets and the last squad car is pulling in for the night, you like to pop a few painkillers, have a sip of whiskey, and survey your miniature world in the fading lamplight. You like how orderly it all looks from above: the residences sorted neatly into identical rows, the looming skyscrapers reduced to the size of your boot, the ghetto safely cordoned off to the side. The silence and stillness. The peace. For just the briefest of moments, you wonder why the real world can’t be so. Then you pour yourself another drink.

///

The first command you receive in This Is the Police is to fire all the black cops. That’s not a matter of interpretation: the directive actually says “Fire all black cops.” In a game that gives you 180 days to play through, this happens on day four. A justification of sorts is offered. It seems that there are bands of racist gangs on the loose in Freeburg, and they have called City Hall to say that any black people in government positions would become targets. Mayor Rogers, the mindlessly bigoted serial rapist that serves as your primary antagonist in the game, decides that it is easier to just fire all of them. Never mind that the police are the people who might put a stop to the racist gangs; risk assessment is paramount in this game, both for you and the mayor.

This initial, eyebrow-raising episode turns out to be a model for the way the rest of the game will proceed. The majority of your time as chief is spent dispatching your police officers to crime scenes, and following up on the results. But your ability to respond to crimes is contingent on having the resources to do so, and these are allocated by City Hall. So, whenever the mayor has a problem that might be best solved through force, you send out the SWAT team. Or if he needs the department to display a particular skin color to earn political capital, you make it so. It’s true that the game does give you the option to turn down these uniformly heinous directives. But if doing so may assuage your conscience, it also hurts the police force, and thus the citizens of Freeburg. The game’s incentive structure essentially forces you into compliance, hence corruption. But underneath it all, it suggests, you’re just trying to do the right thing.

The Freeburg police force has, in fact, an extraordinarily high turnover rate. One day you’re ordered to fire all the old cops on your staff. On another, the mayor tells you that he wants at least four Asian officers present to impress a visitor, so you need to clear out a few spots. But since the game doesn’t actually tell you the race or age of your employees, you are forced to profile: this person’s name sounds kind of Asian; that person looks sufficiently old. You will be penalized for getting it wrong. In case this sounds like a fun or interesting thing to do in a videogame, I assure you it is not. Yet it is relatively innocuous compared to some of your other duties.

you must explicitly authorize the use of force

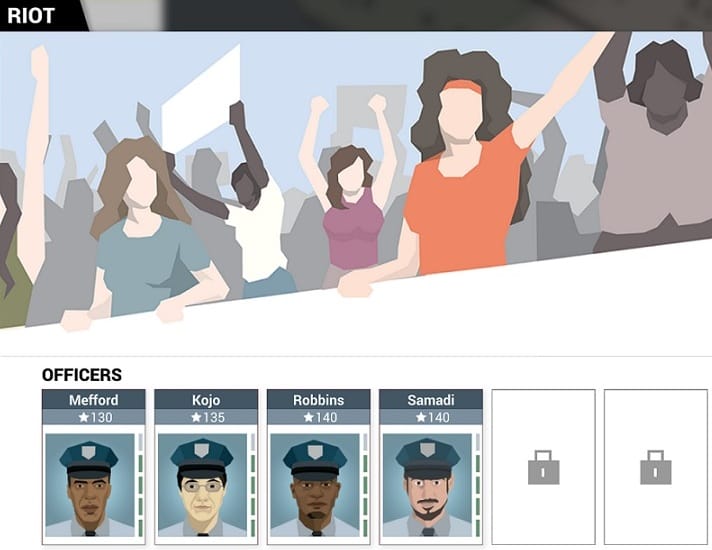

Perhaps the definitive episode of the first half of the game centers around a conflict with “the feminists.” The mayor orders you to send in the SWAT team to shut down a feminist protest at City Hall. To complete the mission as assigned, you must explicitly authorize the use of force: “Let’s show them what intimidation looks like, up close and personal.” Like all other citizens in the game, the feminists are voiceless and faceless. (Quite literally: the game illustrates their bodies without faces.) But when you get in trouble for ordering the police assault, and you have the option of framing one of your own for initiating the violence, the game fills in the dialogue for you. “He couldn’t wait to turn their faces into bloody messes,” it says. Whatever gets you off the hook.

///

This Is the Police is the first game created by Weappy, a small studio in Minsk, Belarus. Like many North Americans, I knew almost nothing about Belarus when I started playing the game. I didn’t know that it is commonly referred to as “Europe’s last dictatorship,” or that sitting President Alexander Lukashenko has been in power since 1994, or that his government has a long and well-documented history of violating human rights. Thinking that some of these facts might be relevant to a game ostensibly critiquing law enforcement, I contacted development lead Ilya Yanovich to get some context for a game that badly needs it.

Yanovich never responded to my questions, but a few days later he posted an open letter on Weappy’s website directed at inquisitive journalists. The letter outlines three “caveats” about the game. First, Yanovich claims that his country’s history is irrelevant to an evaluation of the game: “This Is the Police is not about the United States or any other individual country,” including Belarus. “We deliberately did not specify when and where the events in the game unfold—not because we were being cryptic, but because it doesn’t matter.” The designers want to explore universal issues: “The problems of every individual are the problems of all mankind.”

As noble as this principle is, it is hard to endorse in 2016. Freeburg may be a generic Western city, but not all of humankind lives in generic Western cities. I have no idea what a game called This Is the Police would look like if it was made in Singapore or Iran, but I suspect that it would be very different. This game probably wouldn’t be made in Canada either, at least not in its current form—the sheer proliferation of derogatory language and identity-based violence would be unthinkable in today’s climate, and for good reason. Moreover, the orders to shut down peaceful protests with nightsticks and SWAT teams feel genuinely alien from where I’m sitting, because Canada doesn’t have the same laws against public assembly that Belarus does. These kinds of differences should be highlighted by a game this immersed in real-world affairs, not erased in the name of some fictional ur-state.

Along the same lines, Weappy representatives have apparently been inundated with questions about how their game relates to the scourge of police-related violence currently plaguing America. To their credit, the developers have been consistent and forthright on this issue. They condemn the shootings like the rest of the world, but they started the game long before that conversation picked up traction, and their game has nothing to do with it. Which is true: of all the shades of corruption and villainy explored in This Is the Police, you will never have to answer for the police shooting of an unarmed citizen. One could wish this issue was raised somehow, but I don’t think there is anything here to fault the developers for.

Their final claim to self-exoneration, however, is harder to interpret. “This Is the Police is not a political game, but a human one,” says Yanovich. “We do not believe that the problems discussed in the game are political in nature.” He offers a personal explanation:

A couple of times when I’ve been at protests, I’ve seen people peacefully expressing their dissatisfaction, and receiving a club in the face. Of course, the reasons why people took to the streets, and the reasons they were broken up, are directly related to policy. But that terrible moment when a person suddenly decides that he has the right to hit another person, that devastating moment when the thought enters his mind—that has no relation to governments, parties, or laws. It doesn’t matter what country or continent you’re on, your gender, sexual orientation, skin color, or religion. Because it’s not a matter of politics. It is a question of humanity.

There are two possible ways to interpret this. The first is to take it straightforwardly, in which case we have to ask: what is the point? If This Is the Police doesn’t deal with political problems, then why does the player need to spend hours polishing their racial profiling techniques? Why lie our way through the press conferences? How else should we classify the struggle against scarcity and the heavy hand of that notable politician, the mayor? If gender and skin color don’t matter in this game, then why do we spend so much time beating up women and black people? Where is the humanity that Yanovich speaks of?

Weappy may well need to protect themselves from the law

The other, very real possibility is that This Is the Police is a thoroughly political game, but its creators are unable to admit it. Consider: how do you make a game about a corrupt government in Europe’s last dictatorship? You do so by presenting it as a completely apolitical, “human” story with “no relation to governments, parties, or laws.” If Yanovich’s letter reads a bit like a legal document, that’s because Weappy may well need to protect themselves from the law.

I have no evidence that this is actually the case, of course. But it makes sense of the game in a way Yanovich’s actual words don’t. If Yanovich has himself been a protester, and has seen the effects of violence first-hand, it would make sense to interpret the game he supervised as presenting a critique of that violence. In this scenario, all the bigotry, discrimination, corruption, and brutality of the game has a political purpose, however awkward and offensive it may be on the surface: it is meant to illustrate the brutal reality that activists—especially women and people of color—are faced with in Belarus.

Although this is the explanation I would prefer to believe, it still wouldn’t be enough to redeem the game. For the ultimate failure of This Is the Police is that it makes everyone culpable but the police. When you fire all the black cops on day four, it’s not really your fault: the racist gangs and evil mayor made you do it. When you order the assaults on protesters, you’re just following orders. If this game is any indication, the worst thing a cop ever did was drink too much on the job: all the true evil originates with the higher-ups and lower-downs.

The aesthetic dissonance caused by this sympathy for the corrupt is most acutely felt in the game’s story. I have avoided talking about the copious cutscenes because they are terrible: a half-baked assemblage of noir tropes and gumshoe clichés narrated by, yes, Duke Nukem himself. But most galling is the fact that, in the middle of all this horrific repression, the game genuinely encourages you to feel sympathy for Police Chief Jack Boyd. Your wife will leave you for a younger man, but you’re better off without her; the mafia leaves pieces of your friend hanging from the ceiling fan, but they think you’re a stand-up guy. By the time Boyd started wooing young Lana, one of Mayor Rogers’ rape victims, I had just about reached my limit. Then I checked the stats: 90 days left to go. Jack Boyd isn’t the only one overdrinking.

///

By day 100, you’re starting to lose sight of the goal. They gave you 180 days to finish out your tenure as chief; at first it sounded like a death sentence, now it’s more like a prison sentence. No matter how many bribes you take, your wallet keeps getting thinner. No matter how many cops you set up to be assassinated by the mafia, there’s always someone snitching behind your back. And when, despite everything, you set yourself to the task of actually administering justice, it seems like everyone is working against you.

So you pop a few more Percocets, throw on that Duke Ellington knock-off you snagged on the cheap, and kick your heels up. Then it hits you: why keep policing at all? If they’re going to fire you in a few months anyway, what have you got to lose? The more you think on it, the better the idea sounds. So you fire all your staff. Every cop, every detective. You stop taking calls from the mayor. When you’re not sleepwalking your way through the faceless exchanges that compose your life, you sit at your desk and let the scanner sing you to sleep.

And nothing happens. No citizen protests about the rising crime rate. No outraged calls from City Hall about dereliction of duty. Hardly a peep from the newspapers. Crimes are still being committed, but somehow, the city doesn’t seem to be falling apart. It’s almost like they don’t even need you.

So you sit up. And you go back to work.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.