War games have consistently failed at making me feel like an invader. Their stories, almost always, involve Western troops on top secret missions behind enemy lines—myself and my AI squad mates are supposed to be interlopers, constantly vulnerable amid a foreign, hostile environment. And yet, we master our surroundings, and our enemies within them, entirely. On-screen objective markers tell us where to go. An arsenal of science-fiction weaponry ensures our safety. Videogames are sycophantic. We, the players, must always be comfortable. We must be provided with the necessary equipment and navigational tools so as not to become stuck (or even face considerable challenge), and regularly patted on the back, told that we are good, that we are the hero—we must know that it is our actions, and what we choose, that matters most.

Hitman: Blood Money (2006) is not sycophantic. It values its players’ intelligence and attention above their enjoyment, and certainly above their egos. It’s a game that encourages players to take concomitant responsibility for keeping its story and tone cohesive. Surreptitiously, Blood Money motivates players to think and act in ways that compliment its creators’ vision. Anyone searching for answers to the question of ludonarrative dissonance (I have no idea why that term has become a joke, or why people are skittish about using it) would do well to play Hitman: Blood Money. To put it simply, this is a game where, without realizing, players consistently think and behave like their character. Considering Blood Money’s central character is a sociopathic, inhuman murderer, that is no small feat—the game-makers achieve it by making the player always feel as if they are an invader.

Blood Money’s weakest missions are its most normal. The vineyard, steamboat, wedding, and White House levels take place in locations that are familiar to us due to the prevalence of their real life counterparts—the enemies are merely gangsters, cops and soldiers, housed in recognizable architecture. The sense of being an interloper, inhabiting a space that is alien which can only be successfully traversed if one pays close attention, is felt more strongly in Blood Money’s other sections. The rehab clinic, the Heaven and Hell party, the Mardi Gras parade, and the Playboy mansion-style mountaintop soirée are much more elaborately designed. They are more colorful, more complex, more idiosyncratic—your targets at the vineyard are simply drug dealers; at Mardi Gras, they are a married pair of assassins disguised as giant crows.

Affectations such as these (the pedophile opera singer, killed on stage after the player swaps his prop pistol for the genuine item is another) are often understood as exemplifying Blood Money’s “art style” or its “humor.” But they are more than simple flourishes. Agent 47, the player character, is a human clone: comprised of various people’s DNA, and developed in a laboratory, he is not a person, in the true sense of the word. Nor does he have access to human emotions—specifically, he was bred to be an efficient murderer, and so feels no remorse and no guilt, and does not develop attachment to people. Blood Money’s “art style,” its many strange characters and unique locations, are designed to make players feel as if they, too, are an outsider.

players consistently think and behave like their character

When first playing Blood Money, one may simply marvel at creator IO Interactive’s willing and ability to create distinct and disparate levels—here is a rare example of a game-maker reluctant to recycle textures, enemy designs, and other videogame assets. Further considered, Blood Money’s variety of locations and targets is conducive to creating in the player an assonant frame of mind. Level upon level, she arrives in new and exotic places. Knowledge of basic mechanical conceits may carry over, but she is forced to imbibe and comprehend an unfamiliar setting. And, of course, she is always on her enemy’s turf. 47 does not assassinate his targets out in the street—he hits them at home, invading their domiciles, their parties, and their places of work to (sometimes metaphorically, sometimes literally) kill them in their sleep. In virtually every mission of Blood Money, 47 is a rogue presence. The player, constantly wrong-footed by the changes in surroundings and people, feels as he does, unfamiliar and unattached: a non-human, temporarily trespassing upon a world where she does not fit.

This dynamic is present, also, in Blood Money’s objective and mechanical structure. Levels are open-ended—the player is perhaps given hints, but largely she must devise and execute her own route to her target. Weapons must be smuggled past guards, security cameras must be evaded, a silent and complex assassination is rewarded by the game above a loud, simple one. In short, Blood Money’s levels are self-contained puzzles. The player is given a problem—47 cannot enter this area without alerting the guards—and a solution: by following this lone guard to the bathroom, she can knock him out and take his clothes as a disguise.

If Blood Money wants its player to feel alien in her surroundings, appropriately, its levels are designed to be perplexing. The player cannot simply traverse: she has plot to scheme. For 47, an emotionless non-person, and for the player, who temporarily inhabits new and peculiar game spaces, the successful navigation of which requires effort and forethought, the human world is very literally a puzzle. 47 does not understand and cannot empathize with people. The player arrives at each mission unaware of what to do and how. To comprehend the people and the place around her, she must work hard and pay close attention, and through that process, of steadily evaluating the roles everyone and everything play as pieces in a puzzle, she develops the same detached, dispassionate mindset as Agent 47. Both are disarmed by their lack of understanding of the environments they fleetingly inhabit. Both develop their understandings not through ingratiation but through cool observation.

the human world is very literally a puzzle

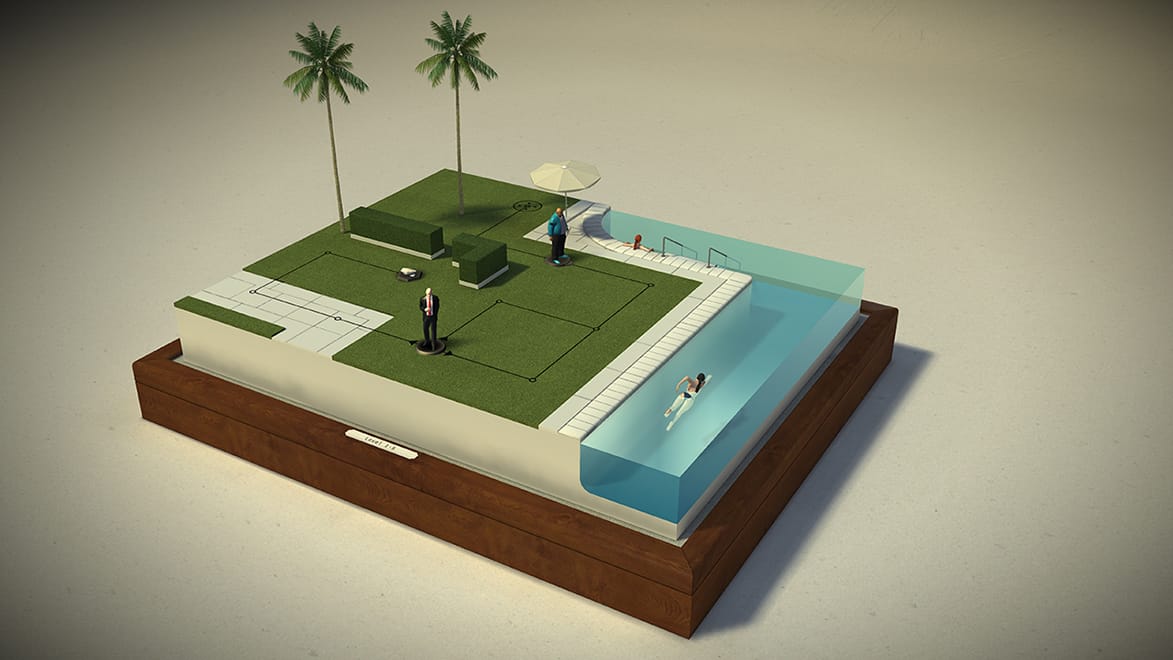

And that cool observation, as well as its puzzling level set-ups, is encouraged by Blood Money’s absence of sound. Save for some choice clips of dialogue and occasional ambient effects, the missions in Blood Money are largely silent—rather than diegetic sound, the player is accompanied by Jesper Kyd’s score. Experiencing the levels this way, able to see but not especially hear the people around her, the player is not only forced to use her eyes and to regard non-player characters as silent game pieces, like those on a chessboard, she is unable to fully immerse in the world around her. Such an aesthetic was taken to its logical conclusion in Hitman GO (2014), an acknowledged puzzle game wherein guards and civilians appear literally as pieces, silent, largely inanimate, all to be coolly removed from the board by the player. Here, 47, again, is a non-human. Humans, to him, are “others.” And in the incongruously quiet levels of Blood Money and the utterly silent boards of Hitman GO, he cannot hear their screams.

In this silent, strange world, constructed with a puzzle-like complexity, a sense of belonging—a sense of ownership, or agency—must be hard won. Hitman: Blood Money, though it casts the player as the world’s greatest assassin, reminds her constantly that she is disarmed, that she does not belong, that in its simulated human world she has no jurisdiction. Too often videogames pander to their players. They make them not just comfortable but confident. In what ought to be dire, disempowering scenarios—a soldier, fighting a war on foreign soil—players are allowed to feel superior, even brazen. Blood Money does not deliberately obfuscate the player.

Its subversion of typical videogame power transference, whereby game-makers bestow upon players as much agency as possible, is not overt. Blood Money is not a snarky game. But it deftly undercuts players’ expectations by placing them into a world in which they do not belong. The player does not merely inhabit 47 physically: unable to hear what the humans are saying, yet encouraged to regard them as they go about peculiar routines. She inhabits him mentally. And in doing so begins to feel less like a videogame player, in the cosseted, pandered to sense, and more like an interloper—a person who must use intelligence and perception, two virtues all too often ignored or even disparaged by videogames, in order to succeed.