In praise of the digital-era obscurity of the Mountain Goats

The Mountain Goats’ new album Beat the Champ came out this week, on CD, LP, and a “Deluxe” colored LP with two extra songs. This is fairly common: most albums come out in a variety of formats. Merge Records notes, however, that, “Deluxe LPs are now out of stock — please check with your favorite local record store on street date!” Maybe you’ll find one.

This scarcity is indicative of a larger quality of the Mountain Goats, among whose legion of devoted fans I count myself. Most people who know me can probably corroborate that. I dig upbeat songs about sad subjects, and there are enough Mountain Goats tracks that I feel like even though I’ve listened consistently for seven or eight years, there are still plenty I haven’t heard, couldn’t recognize, or don’t know every word to. I am, however, about as old as songwriter John Darnielle’s first cassette releases, which means that I’m way too young to have been around when you could still order limited-run cassettes from Shrimper Records catalogs.

Through the nineties, while getting an English degree at Pitzer, Darnielle (as the Mountain Goats), attached to various small labels, put out four studio albums on CD, six smaller-release cassettes, and eight vinyl singles, and music wasn’t even his “main thing for another eight to ten years.” There’s a chance there are still tapes and 45s in dusty second-hand record shops, and some pop up on eBay every so often, but if you really want to collect all five to seven hundred Mountain Goats tracks and keep them on your bookshelf, it’s likely to be enormously expensive, and there’s a good chance it borders on impossible. The band inspires devotion but also a Pokemon-like desire to collect every track, every version of every track, and every physical release.

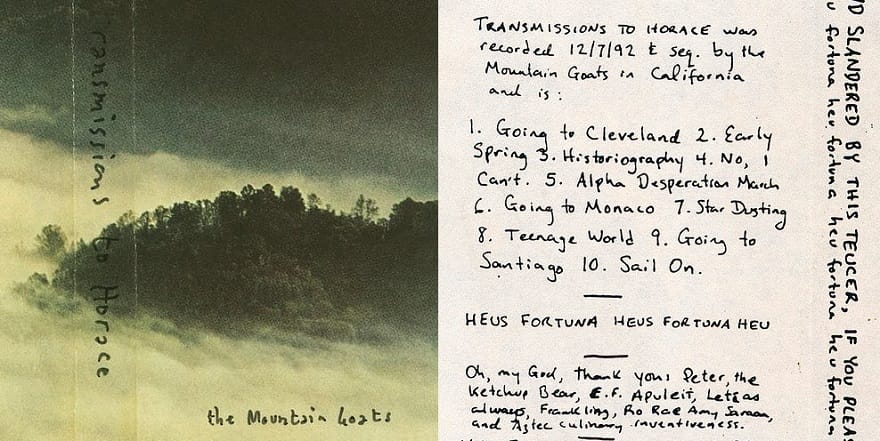

It’s not hard to believe there are 200 Mountain Goats fans out there who’ll never let go of their copies of 1993’s Transmissions to Horace, for example. The tracks from that particular album were collected and re-released on a CD, and this is true of a lot of the Mountain Goats’ stuff, but now the only place you can buy those albums is from other fans or on iTunes. The physical version of it is too precious to get your hands on.

Because of the sharing and collecting fan-culture of the internet, some of those songs that are out of print or that were never even released can be found on wikis or Youtube, or particularly Kyle Barbour’s exhaustive website, which catalogs releases, album art, lyrics, allusions, and so on. It seems sometimes like the varied cover art and pen-scrawled liner notes of early Mountain Goats tapes are a deliberate appeal to ephemera-lovers—one cover doesn’t look like another, they’re torn from atlases, or made with copy machines and crayons.

This digitization of ephemera preserves the work but destroys its transience

In 1995, John recorded an album called Hail and Farewell, Gothenburg. The album went unreleased until it was leaked to the internet nine years later. It became easy to find on filesharing websites, and it’s all over YouTube by now. In response, Darnielle has destroyed the masters to outtakes from other albums, worried that they could be leaked before he was ready to release them. At a concert in 2009 he played a song from Hail and Farewell, Gothenburg, and talked about its leak, and his dissatisfaction with what’s out there: “The more loudly I proclaim its badness, the more entrenched the opposition becomes,” he said, adding, “if you’re listening to that, open up Audacity and pitch-correct it.” The version that’s out there is faulty in some way, and the responsibility of the “true fan” is to do herself the service of fixing it, and of making it the best it could be. (This is putting aside the question of whether or not someone who ignores Darnielle’s wishes is in fact “the true fan.”)

If you type “mountain goats” into YouTube, one of the first suggestions that pops up is “mountain goats you were cool.” That’s the name of a particular track that has never been released on any album. It’s a song that only gets played live. Playing at Carnegie Hall in 2013, Darnielle said, “It’s one of those I’m perverse about, where it should be on a record, but I always like to keep some unreleased. I may buckle with this one eventually.” According to the Mountain Goats wiki, it’s been played at 94 shows since 2010.

A Tumblr user asked John if the band would ever do a live album. “Doubtful,” Darnielle said. “First off, there’s a whole ton of live shows at the Archive.org … [and] there’s also Mountain Goats fans who trade shows, which is rad, totally inspiring to me to know that people care enough to curate collections of our live shows. The sort of industry-standard ‘the band at their best live playing the songs that people like best,’ for us I don’t think that’s an album we want to make.” As I read it, Darnielle is rejecting the idea of a definitive live version and holding up the proliferation of fan versions, the uniqueness of the two times “Tribe of the Horned Heart” (for example) has ever been played, or the Paris version of “September 15 1983” that ends after the first verse, with a promise that the next time the band is in that venue, they’ll play the second verse.

There is so much Mountain Goats ephemera that it’s hard to imagine it would all end up on the web, and at the same time, so much of it has been digitized—the album art, the performances, the extra tracks on a handful of cassettes, all solidified into a canon of sorts. Otherwise fleeting moments become locked, able to be reexamined over and over. If you look for the album art for Transmissions to Horace, only about three images show up, even though as far as I know (not having seen any physical copies), all 200 cassettes have different art. This digitization of ephemera preserves the work but destroys its transience.

In 2002, the Mountain Goats released Tallahassee on 4AD, the biggest label they’d worked with yet. The album release was accompanied by a small website that eventually got taken down. When a fan on Tumblr offered to revive it, Darnielle said, “I’m often happy when things that have run their course are gone; it’s satisfying to me. Nothing is allowed to just go away any more; the archival nature of the web means if you make something, you’re consenting to its decontextualization and reuse forever. Things that exist for a season and are gone are some of the loveliest things in the world, in my opinion; few share that opinion now, but that’s ok, too.” He revisited the topic later, concluding, “May it rest in lost bits.”

///

Header image via SGV Filmworks.

Concert image via JMAWork.