What if there was a game with multiple playthroughs built into it…and each playthrough involved cycling through an entire life? Artist and game designer Prashast Thapan is working on it. Titled 1000 Deaths, and set to be released under his studio, Pariah Interactive, Prashast’s game is an “intertwined web of stories where you’re forced as a player to let go of this idea of the main hero. It forces the player to consider varied perspectives; to understand points of view that may be different from where they started.”

We speak with Prashast about what it means to ‘break’ immersion, how he came to make a game for his undergraduate thesis in graphic design, and why games these days are too long.

Could you talk about your upbringing and your childhood? Was there a moment growing up where you knew you wanted to do something creative in your life?

I’ve been drawing since I was an infant. There was always this inherent attraction to making stuff. It was a good way to channel my introvertedness. I grew up in India, New Delhi specifically. West Delhi, where I grew up, felt like an auxiliary part of Delhi; contrasting starkly with the uptight, sophisticated South Delhi part where I went to school. Looking back, having that perspective from West Delhi to South Delhi gave me the appreciation for contrast that makes me tick.

Our school was a civil services school, so many kids were traveling internationally all the time. I loved getting this gamut of people to be around at home and school. When I think about it, that’s been informing my work. Even until today, understanding the gamut of experiences available and having that perspective that’s just beyond one’s self.

As you know, India has 1,000 dialects, tons of languages—you cross a state border, there’s all sorts of different food, fashion, and culture. There’s stimulation and colors everywhere, so my creative process became more collage-based. I got into that, picking things from here and there and putting them together into something new.

You went to RISD for Graphic Design. I’m curious about what that program was like and how you ended up doing graphic design and making your way into interactive work.

I wanted to go to school for animation initially, but I took an animation class my freshman year. Although I liked the product, I just didn’t like the process. I respect the process, but it just wasn’t for me. I chose graphic design because it seemed like a discipline where you can combine a bunch of disciplines. You’re working on a computer, but you can mix photography with painting. To me, it felt like collage.

It was a little frustrating in the beginning because the program was geared towards formal considerations and nothing else. It was a lot about working with the grid, setting type, layouts, and things like that. Through this frustration with the program, I started to push myself beyond. I took classes in architecture, painting, animation, even music classes at Brown, just trying to absorb as much as possible.

I had friends working in more tangible majors like printmaking, glass, furniture. They would very generously let me use their facilities. I’m happy that I found a way to expand out of graphic design. I had my initial instinct that this discipline is a place to combine media started to become true. I started presenting work that was this amalgamation of other things, which led to really good discussions in the classroom.

I started experimenting with Unity. At the time, it was pretty new, and I was trying to make interactive experiences for my work as much as possible. Somewhere in the middle of the Graphic Design program, I realized we were being taught to communicate information clearly, but to me, that felt one-sided. Using game engines or making interactive experiences allowed an opportunity for your audience to give you feedback. There’s something magical that can happen there where the audience can feel a sense of agency. That’s how I branched off of the traditional graphic design path.

Static Lagoon, a VR game, was your undergraduate thesis. How did this project come about?

We had access to the very first Oculus headset. I was taking classes in the Digital+Media graduate program. I took as many opportunities as I could to use that equipment for various things, culminating in that thesis.

The project was driven by a question which was, “What do you want?” It was driven by this choice anxiety that aspiring graduates have of like, “We’re going to get out of school, get a job.” The possibilities for what we can do are limitless. Back in my parent’s generation, you could be a doctor, lawyer, or engineer…especially in India. Now, the gamut of jobs outside college is so vast.

I could feel this anxiety with my peers. I ended up thinking about simulations as this safe space to practice making decisions without real-life consequences. You can see your choices play out and see the consequences. That was the driving concept behind it. The RestBox was this cushion you could plug into your computer with a USB. The only choice you make in the game is whether, at a given moment, you’re sitting or you’re standing.

In the moments when you’re standing, you’re taking this action. When you’re sitting, you’re on this on-rails experience, but you have the opportunity to stand and branch out of it and go into something else. It seemed simple, but from a technical standpoint, for someone who didn’t know how to code it was quite a challenge—the physical computing and the software aspects. There was a hardware and a software component. I didn’t know much of either.

"Static Lagoon"

Static Lagoon was when I started to consider breaking immersion. The whole world has no walls. I love that idea because it lets you know that this is not supposed to be real. All my work now is driven by the surreal, which is inspired by breaking the fourth wall and providing critical distance. Surrealism does that inherently, because I was disenchanted with these hyper-realistic recreations of reality. They’re technically impressive but can be quite boring. I don’t think it uses the medium to its full potential because you can make anything happen in a simulation. Why would you want to make something that you can see anyway in real life?

The surreal helps to ground that for me. How can you remind the user that they are in a simulation at all times? This notion of questioning how immersed you are in any given moment drives all my work. It all has something to do with breaking immersion.

Are there multiple ways that one can ‘break’ immersion?

I don’t think it’s a tried and tested formula. There’s always an opportunity to break immersion with anything. Using physics that don’t make sense is a way to break immersion. Using audio that doesn’t quite make sense is breaking immersion. It’s a thin line because it could be perceived as unintentional, but the challenge with any of this stuff is how do you make it seem intentional, and for every different project, that’s its problem to solve. I try not to leave any piece untouched without a little bit of that sauce of breaking immersion.

How did you transition to freelancing full-time?

Post-grad, I couldn’t find a job for a long time. All that changed when I moved to New York and started couch-surfing with many friends—hopping around, living with different people. I got a small opportunity at PIN-UP Magazine, then at another small graphic design firm I found on Craigslist. After that, I moved to Interbrand on Fifth Avenue, then I was at OKFocus, now a retired web development company. I moved into MTV as an animator. I did print and digital, mostly focused on motion graphics work. I moved to Vice Media where I was working on their new TV channel, Viceland. Throughout these three years out of college working in television and all graphic design things, I was constantly pursuing game design and development, either in a freelance capacity or collaborating with people.

The place that kicked it off was Babycastles in 2014. It was the launch of Julian Assange’s, book When Google Met WikiLeaks. I remember M.I.A was on Livestream there. She was hanging out with Julian, and it was packed. I kept coming back to the space. They had these bespoke arcade cabinets with all these interesting games, and I loved it. I wrote to them saying, “I have a game, I’d like to show it, I’d like to have a launch party.” It was Static Lagoon. I had a launch there, which was fun.

One of the cofounders, Kunal Gupta, invited me to dinner. We walked up to 32nd in K-Town at a food mall. He suggested I start being part of the team volunteering, which led to this parallel career. I got the chance to collaborate with all sorts of artists—building interactions for the space, setting up physical computing experiences for the space, curating eventually, shows at Babycastles, booking music events.

All this was happening in parallel with my graphic design/television career. At Viceland, I realized my time in the U.S. was so limited, and eight hours of my day were spent in Vice’s basement making videos. That’s when I bit the bullet and quit with a few freelance gigs on my side and transitioned to being a full-time freelancer. I was collaborating with people after hours at MTV. I would sneak them in, we’d use their nice computers to do work on side projects. While I was at Vice, I had my studio. I would bike over there after work and stay there overnight.

Now, you run a game design studio, Pariah. How did that begin?

Pariah is a name that I could attach to the project because I knew this would be something beyond myself. There was a point in time where I realized that I’ve collaborated with so many people on this big game project. It wouldn’t make sense for me to put it out as a solo developer, so I wanted the company for that reason to have a name that my collaborators can get behind and feel proud to publish under.

Having a company in this American structure of capitalism is more beneficial to individuals under that company than being an individual. Those are the two reasons. When it started, it was me getting paid as the company. A few months in, I started to hire contractors as needed for the needs of various projects.

Last year, I started working with Movers & Shakers building AR experiences. Pariah built a few things for them, including Kinfolk, an AR app where you can place unsung heroes from Black history in your AR space and learn about them in a nutshell. Developing for Movers & Shakers gave us the boost we needed, and now we have a full-time team of four. The company has come a long way.

When I started Pariah, I thought it would be a label to put on 1000 Deaths, but it’s become more than that. It’s blurred the line between my practice as well. Right now, running the company is my practice because I’ve had to learn so much, all the different aspects of business.

Right now, my job is to find answers for my clients, my team, for myself, for the company. I’d like to have more time to explore and ask questions. There’s an ebb and flow to it. Some moments in your life you’re asking questions. For me right now, it’s the stage where I have to continuously find answers.

Forcing the means of production to be part of the work itself feels very important.

That’s the business model now. We make the client work, and whatever funds we get from that, we channel it towards the game, which is our investment and our product. In the future, I want to see the company making games. I love everybody I work with. I would love to see us being a game developer and making a mark in that way.

What can you tell us about Pariah’s ongoing and upcoming project, 1000 Deaths?

It started with this idea of, “What if we got rid of this notion of a main protagonist?” That’s so common to most games. You follow this one character throughout the narrative. What if we got rid of it, threw that out of the window. Instead, make it so that you have a cast of characters you care about equally, and you play all of them?

What we found happened was the beliefs and ideas of the character that you’re empathizing with or relating to, in the beginning, that may not matter by the end of the game because you switch characters along the way and grow. You go through these different life stages from baby, to teen, to adult, to elder. At the end of every playthrough, death is guaranteed. This happens in about 15 minutes, maybe half an hour if you take your time. Then you start again. You can make new choices, and that will take you to a different character, perhaps.

Imagine you start with a character with certain beliefs that you empathize with and then you switch to a character that has completely the opposite beliefs and you’re forced to reckon with those. That’s the conceptual framework of the game. It’s a culmination of all the thinking I’ve done in the realm of decision-making, and this notion of breaking immersion I’ve been talking about.

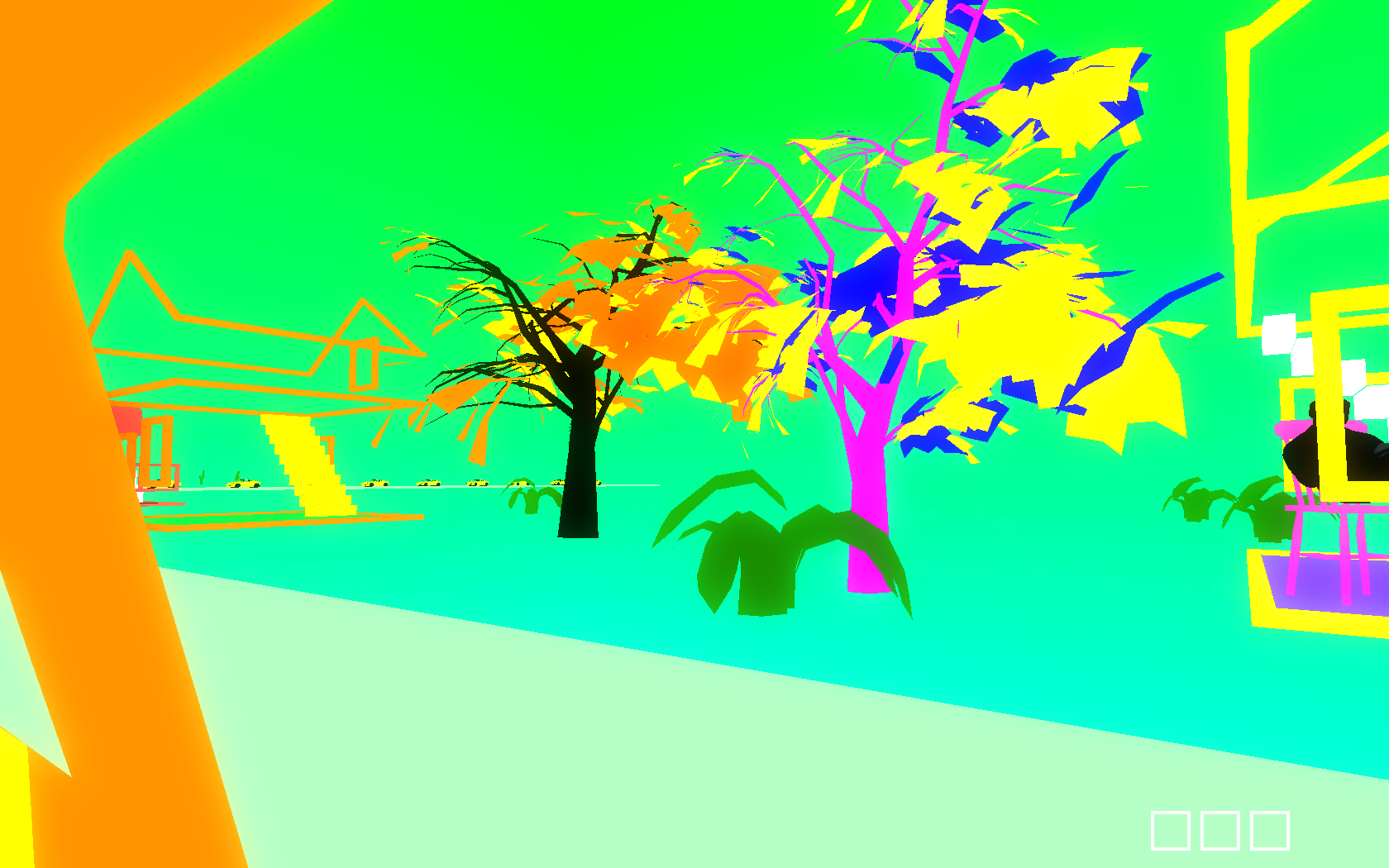

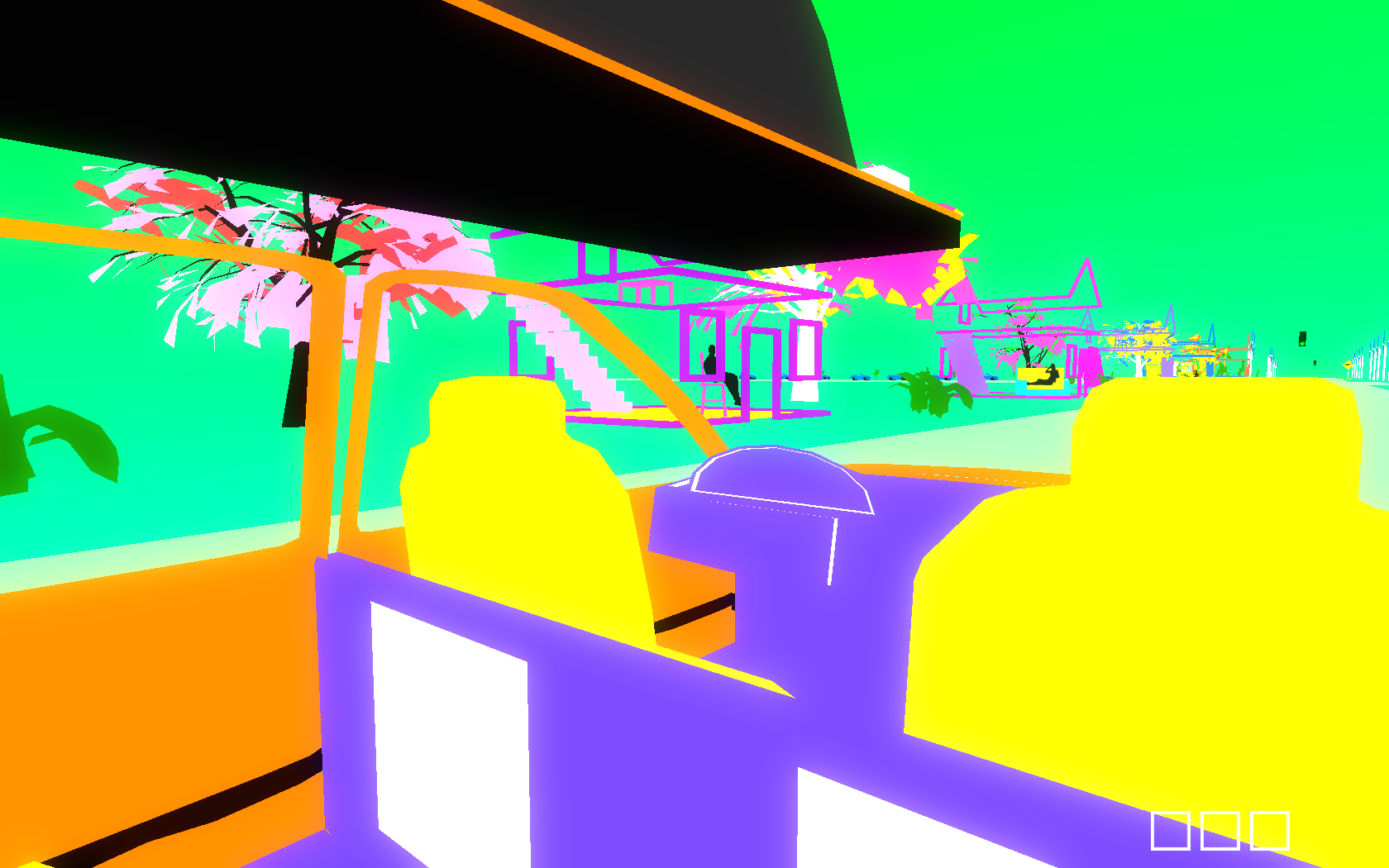

Process stills from "1000 Deaths."

I think games are way too long these days. I saw this opportunity to make a bite-size game that you can pick up, play through in a short amount of time. You can choose to keep doing it, but you can also sit with that one experience for a while to unpack it because it does give you so much to unpack, even in that 20 minutes. Also, many of these narrative games that have decision-making, the actual plot doesn’t change that much.

If you take something like Telltale Games’ Walking Dead, the general plot stays the same. In 1000 Deaths, when you decide, the whole world is radically different from the next branch of the story. That’s why you can take away a lot even in 15 or 20 minutes for a playthrough. It gives you a lot to think about after you put the game off. To me, the game may be escapist in the beginning when you’re playing it. Still, when you put it away because it points to reality so much throughout the game, players of all shapes and sizes will see takeaways that relate to the human experience after they put the game away.

Is there a political end to the game?

All of this is open to interpretation from the player. At the end of the day, whatever our intentions are as developers don’t matter. The players will take away whatever they need to take away. That said, perhaps the hope is players playing this game can remember that there is a wide gamut of beliefs and ideas that others have built over their life. People around us introspect for long periods to solidify their beliefs. It’s served to remind the player that just because someone disagrees with you doesn’t mean that to them, they’re not coming from a place of truth. The game has an outlook of counter-intuitively diving deeper into considering perspectives that may not align with our own, rather than dismissing them as invalid.

Credits

Edited and condensed for clarity. Interview conducted in April 2021.

Links

Follow Prashast on Instagram

Follow Prashast on Twitter