There was a study recently that determined that the manner in which struggle and education are framed to children affects how they learn. Let me explain. A kid does well on a test and her father comes up to her and says, “You did well because you’re smart.” Intelligence is framed as an inherent ability, something that is always present. When this child is confronted with something that is difficult, the researchers say, the kid gives up easily. This is not something they can figure out, something they click to immediately. The kid is discouraged because their natural ability has failed them. A child that is told that she did well because she studied for hours on end is taught a different lesson. It is not the answer that matters so much as the struggle to arrive at it.

868-HACK is a roguelike, which, if you know anything about roguelikes, might put you on edge. It is a genre built on failure. Its hallmarks—randomized elements with each play to keep the player destabilized, forced restarting upon death—are not meant to assure or coddle. You need to learn the game inside and out to cope with what it throws at you. It’s a genre less about mastery, than the attempts at mastery. It is a genre of practice and process.

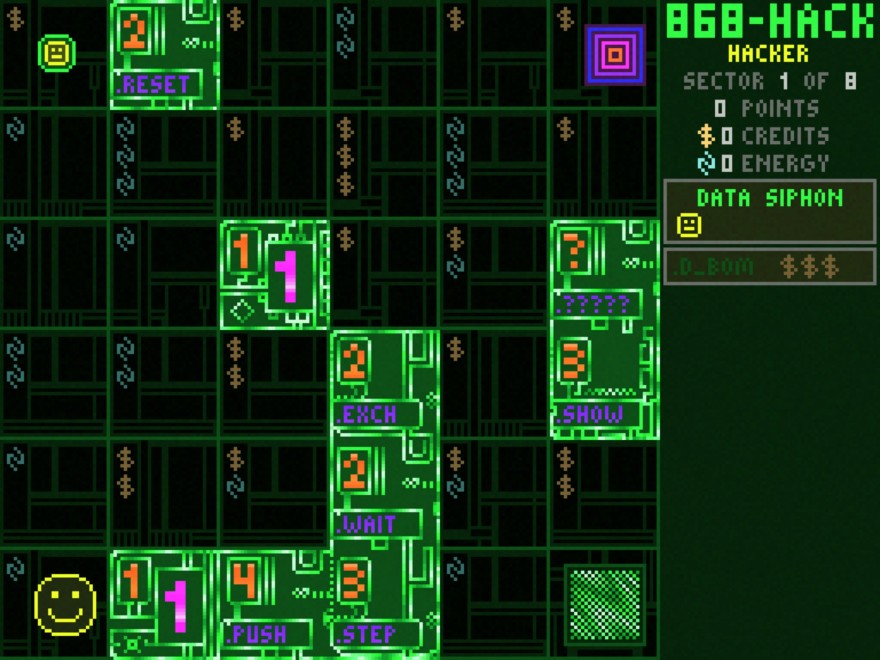

I’m bringing this up because 868-HACK will not immediately unspool in front of you. Load it up and there are hints of other genres and ideas, but it isn’t recognizable from the get-go. There’s a 6 by 6 grid with a smiley face avatar. The goal is to get as many points as possible. You do that by moving around the grid collecting finite tools called siphons that, when placed, capture resources in adjacent squares. Siphons can unlock programs, which are pretty much abilities, but unlocking them also unleash ugly bitmap creatures that try to get in your way. Every time you move or attack, the enemies get a chance to react. Infinity can pass while I try figuring out the next move.

868-HACK presents itself with a thin tutorial and questions pop up immediately: What do the various programs do? (Different things. Push pushes enemies away from you, Step gives you a free move without the enemy reacting, etc, etc.) What do the different enemies do? (The purple enemies move twice in one turn. Pink ones can go through walls. Orange ones take more damage, etc, etc.) What does that little number in the program mean? (The number of enemies that will appear when you siphon it). These are replaced with other questions, but, more importantly, with time and patience, some answers.

Each run of the game rearranges all the existing elements in different ways: new programs are available, the grid is mapped out differently, new enemies pop up. The rules always stay the same, but it’s about showing off how well you understand them. 868-HACK‘s smaller scale means that every decision feels tactical. You know the old Sid Meier maxim about great games being “a series of interesting choices” that so many designers cite and so few actually pull off? Roguelikes like to sprawl. Most pile layers on top of layers of rules, all interacting simultaneously, like a shambolic Rube Goldberg machine. At their worst, they will overwhelm and bewilder, collapse upon you before you have any idea what just happened. 868-HACK is less like genre granddaddy Nethack, a large machine with many moving gears that produces something unexpected, and, instead, like chess, a game that gets deeper because of the configuration of its small set of tactics.

868-HACK allows for high score runs, but also tracks scores along multiple consecutive runs, assuming you survive. This reveals something important about the game: 868-HACK isn’t about quick payoffs. Each run of the game rearranges all the existing elements in different ways: new programs are available, the grid is mapped out differently, new enemies pop up. And new things are learned every time it’s played, new effective combinations of programs, new enemy behaviours to exploit, new ways of using the geography of the grid. Each is learned from failing, and that’s the cycle: Start, bump my head against the game, and fall down. The rules always stay the same, but it’s about showing off how well you understand them.

Its cyberpunk kid-in-the-machine vibe suits the rigidity of these rules. Michael Brough could’ve dressed the game in a magic and elves aesthetic, but it’s been done. What better metaphor than the imagined world of circuit boards and lines of code, with its emphasis on cold logic?

But it’s not as simple as that. Michael Brough has made the cracks in technology a motif in his work. Whether it is making use of limited choices in the overlooked Glitch Tank, or the meticulous puzzles giving way to world-destroying powers in Corrypt, Brough makes games that are as much about the rigid rules as about undermining them. In 868-HACK it takes shape in finding ways to use the program behaviors in tandem to create unexpected results, or knowing how the enemies move and letting it lead them to their doom.

Pitting technology against itself is becoming increasingly common in our own lives. The word “hack” has escaped its subcultural cradle and has now become shorthand for anything that improves one’s quality of life. Who doesn’t know somebody who’s jailbreaked their phone? Various friends of mine have clever workarounds to get Hulu in Canada. The consequence of having more technology in our lives is learning to work around its limitations.

Every time I play 868-HACK I take it apart and try to reassemble it. I usually fail and that’s fine. That is after all, part of the process.