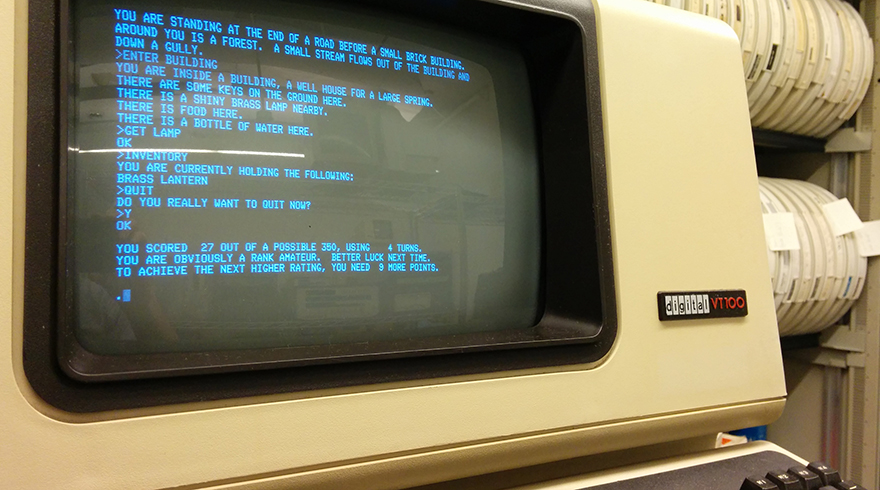

Colossal Cave Adventure (or, Adventure for short) isn’t exactly a familiar title today. Developed during the early 1970s, Adventure was written by programmer Will Crowther while working for Bolt, Beranek and Newman. Crowther was an advent cave explorer, and had vast experience surveying the Kentucky caves. So, combining his love for caverning with his passion for fantasy role-playing, Crowther wrote a short interactive story about exploring a fantastical cave for his daughters. With the help of programmer Don Woods, the game quickly spread across the fledgling internet, and became an instant phenomenon. By the late 1970s, Adventure had ushered in a brand new videogame genre: adventure games.

Up until the mid-1980s, adventure games were predominantly based around interactive fiction. But when Roberta and Ken Williams stumbled across Adventure in the late 1970s, they decided to take their own shot at the genre. By 1982, Sierra On-Line was born, and, unlike the original Adventure, Sierra’s adventure games featured color pictures for the player to look at while solving interactive puzzles. The graphical adventure game was born, and, by the end of 1984, Sierra solidified the genre with King’s Quest, an epic Medieval journey which cast the player in the role of the daring knight Sir Grahame. For the first time, players moved through the world using their keyboard’s arrow keys, and typing in text commands—such as “open the door” or “talk to the king”—to learn more about the Kingdom of Daventry. King’s Quest’s interactive world was a major hit on the Tandy 1000, and Sierra soon capitalized on the game’s success with games like Space Quest, Police Quest, and Leisure Suit Larry.

Since then, graphical adventure games have become a classic genre in videogaming. Today’s players may fondly remember their first time playing through Tim Schafer’s Day of the Tentacle, Robyn and Rand Miller’s Myst, LucasArts’s Grim Fandango, and Sierra On-Line’s horror classic Phantasmagoria. Granted, adventure games aren’t exactly a relic of the past, either. In recent years, there’s been an enormous resurgence in popularity for the classics of the 1980s and ‘90s, thanks in part to Telltale Games’ success and Strong Bad’s Cool Game for Attractive People, up through more recent efforts like Dropsy and Life is Strange. Over 40 years after its debut, adventure games continue to interest players new and old alike.

Playing a graphical adventure game is, for the most part, a fairly standardized experience. Players use the arrow keys to walk around the world, and interact with people and objects through a point-and-click interface. Sometimes players have to hold onto items in order to solve puzzles, or ask for help from important characters. Either way, most adventure games are built around resolving conflicts and unlocking more of the story. The experience is relatively laid-back, and most graphical adventure games rarely deviate from the point-and-click interface.

But alternative games developers love to play around with our traditional expectations of games, and developer Arielle “Slimekat” Grimes is no exception. As an altgames developer, most of Grimes’s work uses gaming as a sort of confessional interaction with the player. She pours herself into her games’ development, and builds her work around her experiences and feelings.

When I reached out to Grimes earlier this year, she emphasized how games let her communicate concepts to the player in a way that other mediums simply do not allow.

“I believe that the ‘engagement loop’ of players interfacing with a game, the series of inputs and outputs, can create a better understanding of ideas and concepts,” she told me. “It’s through the engagement that a player gets to connect with the content of a game—and when that content is emotional, [it] allows them to engage with what may be foreign to them.”

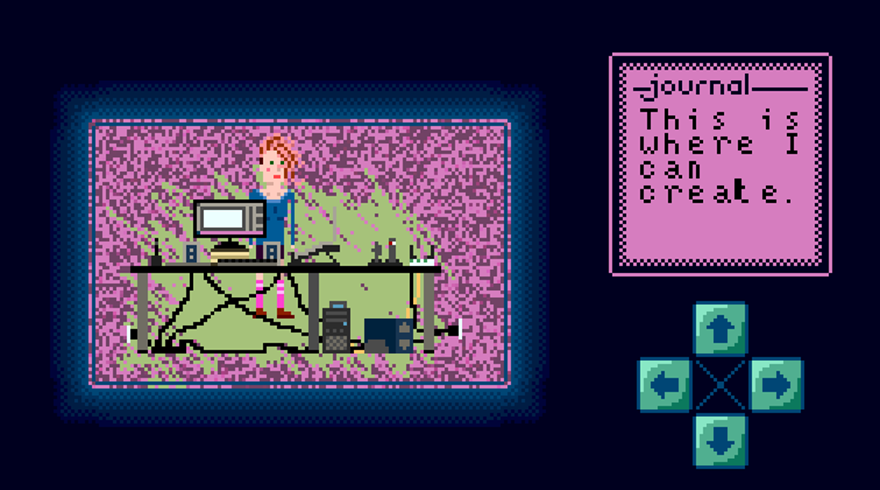

These ideas can be seen in practice in her expressionist videogame, What Now?. Described by Grimes as an “adventure in sensory overload and emotional breakdown,” players take on the role of an unnamed female protagonist, interacting with different objects found throughout her room, such as a bed, a computer desk, a bookshelf, and a mirror. Each of these items trigger a different journal entry about the player character’s thoughts and feelings while looking at the object.

However, Grimes isn’t very interested in the physical appearance of these objects. Unlike Adventure or King’s Quest, each piece of furniture has a deeply introspective meaning to the player character. She reflects on the conflicting emotions found inside her head, and each item builds a picture of her inner emptiness and despair.

Sounds simple enough, but Grimes adds a twist. If the player moves too quickly through the world, small blue and green pixels begin to cover the player character’s body. If the player keeps on moving, her character will become engulfed in an array of colors—first starting with the player character, then spreading throughout the room, until the entire world corrupts into a pixelated mess. The game begins to shut down, as the user interface fades into the player character, blocking out the bedroom world.

“You left me to rot IT NEVER ENDS WHY IS THIS,” the protagonist writes in her journal. Words flash in front of the player. “Screaming won’t make it stop,” she says. “It keeps happening.” And then the game fades, and restarts at the title screen.

“This game, it came from an emptiness in my life,” Grimes told me. “I wanted to convey to the player exactly where I was in my life at that point. Living in a space that is newly wholly your own space, dealing with the newfound emptiness, and the reminders of what was, everywhere around you.

According to Grimes, she began with the idea of “standing still,” and refusing to address emotional pain or anxiety. “We all know this isn’t healthy, or productive,” she explained, “and that we have to accomplish things—and even as we try we may still break down.”

Most players take movement for granted in adventure games. We assume that walking up, down, left, or right is always a safe choice. But Grimes breaks the rules in What Now?, and asks the player not to take freedom of movement as a given right. Instead, moving forward is dangerous. It overwhelms the player character and shuts down the game. So if the player wants to learn more about her character’s feelings, then they need to walk slowly, and in short steps. They need to play by Grimes’s rules. Otherwise, the world will start shaking back and forth, as the game fades away into the player character.

In the original version of What Now?, there was no end state to the game. Rather, if players moved too fast, the barrage of pixels mess would appear on screen and envelope the player character, but the game itself would never restart. However, when Grimes updated What Now? in 2015, she made the glitch mechanic a much more sudden experience. Instead, if the player moves too far while their character is glitching, the game will begin to shut down. Grimes refers to this as an “endpoint” that activates a “game loop.”

“I was preparing the game for its first proper public showing, and therefore needed an experience that could come to a defined end, and loop over so that I could generally not have to worry about the game needing to be reset,” she explained. “The original release was very ambiguous in its ‘meaning,’ and what the player was to take from it, after the experience is complete.”

But meaning is much more clear in the latest rendition of What Now? Seeing Grimes’s player character lament her loneliness as her room shakes uncontrollably is uncomfortable, to say the least. It replicates feeling overwhelmed quite well.

Granted, Arielle Grimes saw most of What Now?’s development as a deeply personal look at her own experiences with anxiety, rumination, and regret. But when she took the updated version of What Now? to Bit Bazar #5 in Toronto, she was amazed by her players’ responses.

“I was surprised to see kids drawn to my work, and to see even the antsiest of kids work through the whole demo,” she said. “By far the most stand-out reception was somebody who ended their playthrough smiling and crying. They thanked me, but were unable to talk to me directly about the experience. They were very overwhelmed.”

Colossal Cave Adventure and What Now? come from two radically different backgrounds. The former is an interactive journey through a Kentucky cave, developed by a computer programmer in the 1970s; the latter, a highly personal and introspective look at a young woman’s struggles with loneliness and anxiety. At first glance, it’s difficult to classify both titles as “adventure games.” Both works are dealing with different issues, and draw in different kinds of players.

But there’s something important that both games share in common—they tell a story. They share an adventure with the player. Whether it’s a journey through a fantasy cave, or a voyage through a young woman’s mind, both games are about exploration and understanding. We learn and grow from the game world, even amidst the challenges we are presented.

When Arielle Grimes sat down to develop What Now?, she certainly wasn’t thinking of the evolution of adventure gaming. It’s hard to say King’s Quest was directly on her mind. But, in some ways, she ended up contributing to the genre’s growth. She challenged our understanding of what it means to play an adventure game. And in 2015, thinking differently about what it means to develop a videogame is more important than ever—even if alternative games make us feel a little uncomfortable in the process.

///

Slimekat is an independent developer, 2D artist, and audio designer. Her work can be found on her official website, and she can be found on Twitter as @slimekat.

//

Photo of Colossal Cave Adventure by autopilot via Wikipedia Commons