What’s odd about Blade Runner is that it’s an artefact of the past about our present. And it is wrong. It’s set in a rendition of 2019—which isn’t far away now—which has android technology way more advanced than where we’re currently at, and also has flying cars for everybody, yet the denizens of its stark metropolis don’t even have HD screens. Oddly, these anachronisms, which are scattered throughout in bruising obviousness, only add to the dense sci-fi plumage of this slow-beat retro-future.

It’s a film that helms firmly from the early ’80s, during which the 21st century promise opened up imaginations to wild technological fantasy much more fascinating than the reality as we now know it. It’s a future that is without the sleekness of Apple products, instead branching off from the clunky hi-tech of the late ’70s: VHS tapes, Pong, super cars, and the microwave oven.

In one iconic scene from the film, replicant bounty hunter Rick Deckard sits down at a table inside rich guy Tyrell’s lavish pad, the latter having made his fortune by manufacturing the android slaves that the former hunts. Deckard and the LAPD’s method of discerning replicants from humans is to use the Voight-Kampff test—a type of empathy assessment—as it is nearly impossible to do so otherwise. Tyrell tries to trick Deckard’s test by asking him to perform it on his assistant Rachael who, it turns out, is a replicant, but she’s one of Tyrell’s new line that have memory implants, which makes it even more difficult to separate the machines from us.

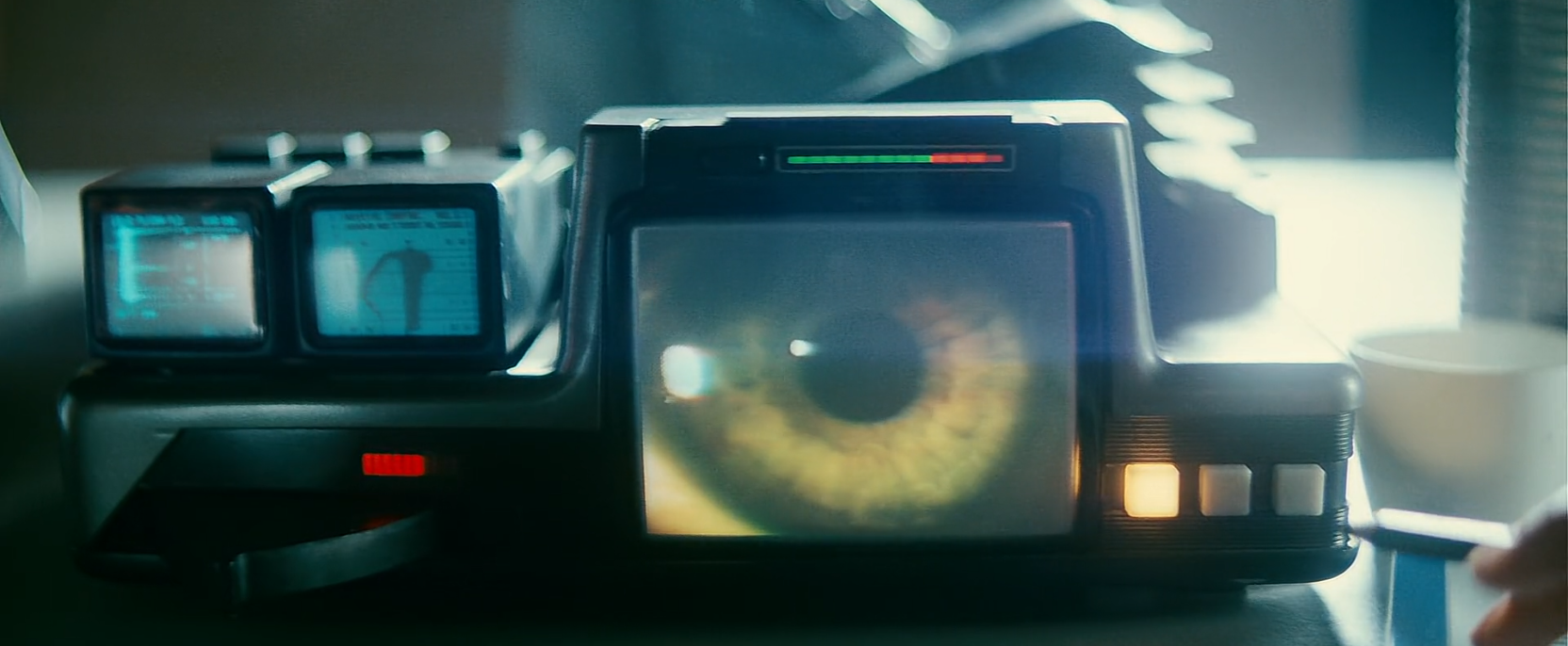

The Voight-Kampff test is proposed to us, the audience, as a test of futuristic proportions. Back in 1982, sure, but now it is so obviously not. We see Deckard flip out the apparatus from his briefcase, setting up tiny monitors with scientific-looking interfaces, connected by wires and providing large-scale feedback with a range of flashing lights and low hums. These analog-based polygraphic instruments will, supposedly, collect biodata by measuring capillary dilation to determine the levels of a subject’s empathy. Yeah right.

Deckard focuses the device on Rachael’s face, zooming in on her pupils, and then asks a series of questions that typically involve a person or animal being caused distress. A cat skin wallet. A collection of dead butterflies. A wasp crawling on the arm. A husband that hangs a poster of a nude woman on a bedroom wall. Rachael smokes a cigarette with heavy drags so as to hide behind a wispy wall while batting off Deckard’s questions, obviously perturbed by having them thrust at her.

It’s this scene that the micro-game Rachel recreates with supreme lo-fi crunch. It’s made to look as if it were produced using the technology that would have been available to game makers at the time of the film’s release, as if it were the official videogame adaptation. What it does right is include tracking lines and a grainy bass hum throughout. Deckard’s boxy machines are also rendered appropriately with garish pastels and indecipherable LED dances.

Rachael the replicant is also animated gloriously with her stern look, upturned eyes, and generally opposing demeanor. You’re tasked with answering the questions as her, choosing from three possible answers, all of which steadily defer to mocking the test itself as the questions go on. By the end it all feels a little pointless which, while not satisfying as a player, does sync up with the surge in the film’s themes towards questioning the reliabilty of the Voight-Kampff test as well as the politics in looking for differences between humans and replicants.

The greater point here is that, despite the obviously aged technology, this scene in the film still works with aplomb today, both as a piece of cinema and as a lo-fi videogame. It’s helped along by Blade Runner‘s suffusion of film noir: the dark smoky room, the shadows carving up faces, Deckard’s large-collared brown overcoat. All this gives the scene a classic cinematic feel, bringing in the prime cut of 1940s film style to a fiction about the future. It’s this collision of new and old between the cinematography and the script that makes the anachronistic tech not feel out-of-place.

It’s a film that draws from the past to inform its vision of the future, and it determinedly cares more for being true to that artistic projection of this fiction, than it does being accurate to what the reality might be. That’s why it feels right to recreate it as a piece of early electronic entertainment and not one with a more modern production.