Superbrothers: Sword & Sworcery EP was released on Steam two weeks ago. The game’s move to a new platform was met with all-around praise. But its change from iPad to PC, from tap to click, deserves more attention.

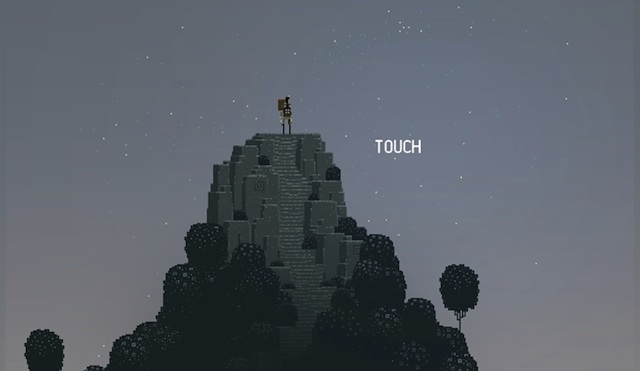

Unlike many other canyons, caves, and mountains in videogames, the game’s landscape is made beautiful through mellow colors and minimal visual details. The game feels like a folktale, rather than a realistic and meandering epic like Skyrim. The original version of Sworcery came together around its interface, which worked in harmony with sound, visuals, and text to create something magnificent. It’s the same as rocks forming together to create a mountain. This is where land art comes in.

Off the shore of the Great Salt Lake, near Rozel Point in Utah, exists a 1,500-foot-long, 15-foot-wide, counterclockwise coil made of mud, salt crystals, basalt rocks, and water. The coil, known as Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty (1970), is one of the best-known works of land art, also known as earth art and earthworks.

Land art is organic, raw, and inseparable from the earth. It can be indoors or outdoors. The purpose is to bring inside something from nature, or to leave behind the white walls of a gallery. Natural materials like metal, concrete, or trees are favored over artificial and synthetic ones. Scale, site, and change are important principles in earthworks.

Videogames are not land art, but neither are they anti-land art. Videogames can make a deeper connection between player and virtual landscape if they experiment with scale, site, and change. Too often do we explore generic glaciers, vapid volcanoes, or awkward panda-filled communities from the “mysterious” Far East without any pause or hesitation.

Superbrothers writes that the PC edition of Sworcery, “is intended to be a faithful representation of the original S&S: EP experience.” But its land and lore can’t be given respect on a PC. The touch interface of Sworcery is what makes its virtual world different and more intriguing than other game worlds. It does this through small scale.

Scale

As Smithson points out in a memorable quote, “A crack in the wall if viewed in terms of scale, not size, could be called the Grand Canyon.” Spiral Jetty might be massive in person, but there is a value in dirt, whether it is viewed from afar or grasped in the palm of your hand.

Like Spiral Jetty, Sworcery is focused, central, and minimal. The game is not laden with stats, world maps, or experience points. These aspects would only get in the way of the interface and virtual landscape. Revelation, discovery, and reaction are created from a pinch to zoom, or an unpinch to zoom out. The pinch becomes a tool for experience, exploration, and investigation.

But in many games, landscapes are transitional non-places. The generic glaciers only serve as a means to an end, as a stepping-stone. There is little point to the generic glaciers if the glacial goblins are not worth killing. In massively multiplayer online games like Final Fantasy XI or World of Warcraft, entire landscapes are devalued if the monsters drop worthless items or provide low experience points. An entire ecosystem is killed off because it does not fit some sort of gratification. A player might enter a certain area only once or twice, just to complete a quest. Once players reach level 99, entire locations are forgotten in favor of camping in one or two spots where particularly enticing monsters appear.

Why are there so many Grand Canyons in games, and not more cracks in the wall? The land gets tromped on, rather than strolled through. In Sworcery, the world might need saving, but that does not mean any traversed space is wasted. Immersion occurs without pointless enormity. Touch aids the experience. The first encounter with a ghost is frightening on a small screen. Quickly tapping and zooming out to escape is intense. It is the constraint of the screen size, and a relationship to touch, that makes the moment special. The familiar and unemotional click of a mouse can take that experience away.

Site

Smithson’s destination was chosen for several factors. The briny reddish hue in Salt Lake symbolizes blood and connects us to the primordial microorganisms floating in the water. The spiral is a symbolic shape of growth and reduction. This echoes the salt crystals in the lake, which grow in a spiral formation.

Site specificity for a videogame should not only refer to an in-game location, but also to the entire interface and platform. The touchscreen is the true site of Sworcery. An iPad and a tiny iPhone keep the game tactile. Intimacy is gained from the strum of a waterfall or the tap of a wiggly bush. Console-exclusive games may be site-specific, but the term “console-exclusive” can feel more corporate and gridlocked than instinctive and natural.

For a time, Sworcery was site-specific to the iPad and iPhone. The game’s interface and its virtual environment were deeply intertwined, through actions like shaking the iPhone to stir up a lightning bolt and rotating the device to open a book or enter into battle.

Site goes even deeper when considering where the game is played. Playing on a small screen, at night, and with headphones on becomes a mystic experience, especially in the dream world. Jamming with musician Jim Guthrie, tapping trees to make them glow, or swiping a cloud to make it hum—these all meld with the intimacy of Sworcery. The change from tap to click makes this a mechanical experience rather than an organic one. It adds an unnecessary third party to the intimacy.

Preserving intimacy all comes down to intentions. The point-and-click structure of Sworcery did originate with PC adventure games, and it does make sense to want the game to reach multiple audiences. However, maybe moving the game to the mouse is a step backward for the point-and-click genre. Point-and-touch can’t emerge until “click” is out of the picture.

A defining conclusion to our experience is lost because of how easy it is to transfer data. And plenty of ports don’t survive the transition. The newest memory and experience of Marvel vs. Capcom 2 is now a poorly ported iPhone version—the illustrious Dreamcast version fades further into the past.

Change

Change and transition was a natural event to Smithson. Entropy was a key factor. No two people see Spiral Jetty in the same way, whether by viewpoints or when they arrive. A flood or drought can submerge or raise the jetty. Aspects like global warming, oil drilling, and Mother Nature all affect the artwork with time.

Smithson embraced change and wanted it to happen. But all types of art face issues in longevity. Recently, even Keith Haring’s graffiti mural in Australia underwent debates on repainting. Spiral Jetty faces similar issues in ownership and preservation. Change, however, does not mean Smithson would have been okay with a Spiral Jetty gallery reconstruction, with the exact same rocks and dirt—or even an outdoor reconstruction of new rocks to make the artwork look exactly like it did back in 1970.

How then should videogames age? What is sacred and unchangeable about the landscapes we traverse? A port can extend play to all sorts of people, but it veers from original intentions; scale and site-specificity, as values, are diminished. Videogames, in their entry into museums and the realms of art history, now face these issues.

The move from platform to platform is an avoidance of death for a videogame. Nothing really dies off, nowadays—at least visually. But if a videogame’s interface is unique and special, it should not be left behind in the passage of time. The game’s move to Steam will fundamentally alter our long-term perception and understanding of Sworcery.

These issues are ultimately tied to memory. How many glaciers in MMOs have melted away from our minds, and what will Sworcery be like in five or 10 years? Nothing is set in stone, but in the end all you’re really left with are stories.

In this regard, Spiral Jetty and Sworcery cross paths once more. Smithson understood that not everyone could make it to Utah to witness Spiral Jetty, so he made a film. He spiraled around the artwork by helicopter—zooming and flying in, out, and all around. The perspective is impossible to experience from land. Once Spiral Jetty erodes to dust, the land will be remembered through the film. The tweet mechanic of Sworcery works in a similar way. Throughout the game you are given the option to record your experience by sending the character’s thoughts and opinions to Twitter. Not every piece of text requires a tweet, which allows for a bit of customization in detailing the quest. Your experience lives on in an archive of sorts. This online archive serves only as a reminder of the experience. In the video of Spiral Jetty you cannot feel the wind at your back, or the heat from the sun; and in the tweets of Sworcery all that’s left is lore.

This allows the work to live on in a special way. But if the interface defines the landscape, it too should be maintained. Mother Nature can whittle away Spiral Jetty, but this was part of Smithson’s intention in placing his work out in the real world. Sworcery can be ported and remade forever, but the experience will always change. In our consumption and reproduction, let’s not forget where the myth began.