1. Pooh Sticks – A single stick drifts toward the distant horizon on the surface of a moonlit lake as the person who threw it into the water watches from a small stone bridge.

2. A country road. A tree. Evening. – A grey evening provides a miserable backdrop to a forlorn scene in which one person waits for Godot beside a leafless tree.

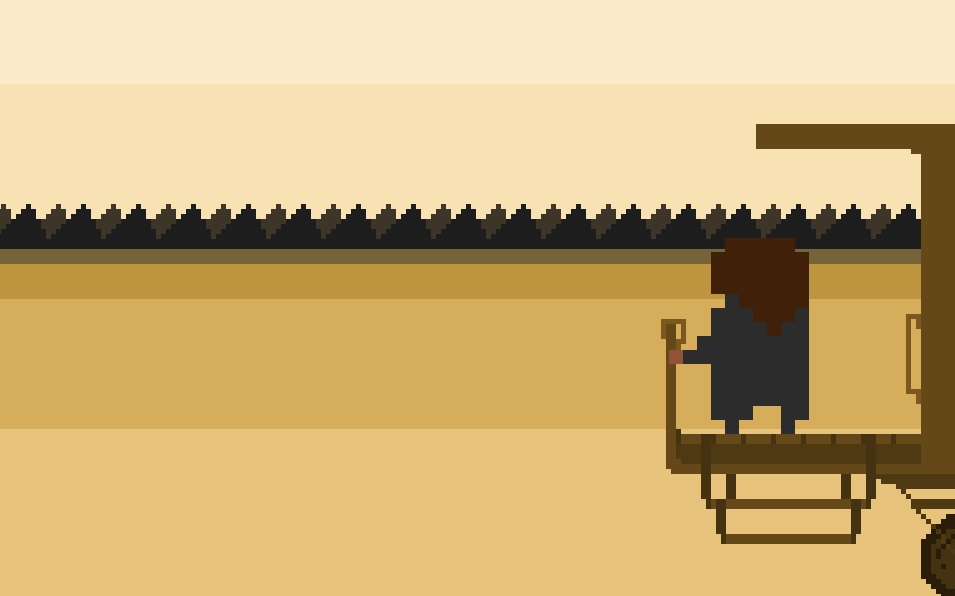

3. A Journey – A person looks out across the scrolling golden distance on the back of a vehicle; it feels like the start or the end of a long journey.

///

It’s possible to play André Blyth’s experimental narrative vignettes and to pass them off as unfinished and uninspired. They’re rapid prototypes that impress upon you evocative, trenchant moments. The typical purpose behind this form of speedy videogame development is part of what’s called “iterative design.”

The connotation with this is that these small videogames are used by artists and designers only to refine processes and ideas in preparation for larger projects. This isn’t the case with

Interpretation is almost unavoidable due to the importance that this single moment is given, which tells us it must be significant, as why else would it be highlighted in such a way? The result is a number of unanswered questions that we are bound to ask when playing these vignettes, such as “who is this character?” and “why are they doing this?”

Following Bradbury’s example,

Bradbury’s stories weren’t the only inspiration for

This method of transfer from mechanic to storytelling is what

What Blyth achieves is up for you to decide, but there is a quotation that he picks out himself from Liz Ryerson’s IndieCade 2014 talk “Embracing the New Flesh” that should provide food for thought….

“while most media tends to flatten and flop on the ground upon further analysis, films like Videodrome or The Shining continue to just unfold like an infinitely layered flower and have a life far after their making. and that’s because The Shining or Videodrome embrace their form. they embrace the plasticity of it. they love their images, and their symbols. they love every detail and shot composition.”

You can download André Blyth’s games over on itch.io for free.