Liyla and the Shadows of War is a game about a young girl living in Gaza during the 2014 Israel-Gaza conflict. Unfortunately, I can’t tell you much more than that because Apple has declared it too political to count as a game in its App Store.

On Tuesday afternoon, developer Rasheed Abueideh said Liyla had been rejected for not being appropriate for the “Game” category and shared a message from Apple that read:

As we discussed, please revise the app category for your app and remove it from Games, since we found that your app is not appropriate in the Games category. It would be more appropriate to categorize your app in News or reference for example. In addition, please revise the marketing text for your app to remove references to the app being a game.

A version of this story comes up every few months, and the same answers generally apply. Much of the silliness of declaring that Liyla is not a game is also true of banning all games with the confederate flag, even those that use it in an appropriately historic manner. It is nevertheless worth considering this latest absurdity because the gradual accretion of silly incidents allows us to gain a limited insight into the closed world that is Apple’s App Store.

Apple’s walled garden is… designed to ensure inconsistencies

Apple’s power over the app ecosystem is attributable, in part, to both its size and imprecision. According to research by Parks Associates, Apple represents 40 percent of the US smartphone market, which makes it hard for developers to simply ignore the Apple and its app ecosystem. For all but the most technical of users, the App Store is the only way of adding apps. Apple’s guidance to developers, however, is hardly helpful. The company’s guide is peppered with vague statements such as:

We will reject Apps for any content or behavior that we believe is over the line. What line, you ask? Well, as a Supreme Court Justice once said, “I’ll know it when I see it”. And we think that you will also know it when you cross it.

Really?

Potter Stewart’s description of pornography, it should be noted, has not held up as a rigorous system for discussing explicit content. Standards vary by community, and allowing one group to judge the material produced by another usually ends badly. The community standards approach also tends to work out especially poorly for underrepresented minorities. All of the flaws of the legal model Apple cites in its developers guide can be seen in the Liyla incident: the line is not apparent to everyone, and here it has been used to reject a story about a Palestinian girl.

The squishiness of these rules puts creators at a disadvantage. All they can do is guess what Apple thinks based on past decisions, and even that may not be enough. As with content guidelines on social networks, this sort of abstract regulation allows for capriciousness with little recourse. This structure encourages an anticipatory form of compliance, or what you might call risk aversion. Apple’s walled garden is, in a sense, designed to ensure inconsistencies.

We ask too much of the oppressed

It is therefore easy to point out the various contradictions in Apple’s rulings. When I played it in February, the emphatically political Peacemaker: Israeli Palestinian Conflict, was available from the App Store. Why did it make the initial cut, but Liyla did not? (Peacemaker was unavailable as of Wednesday night. UPDATE May 19, 2:36 pm: Peacemaker‘s developers have confirmed that there is “nothing interesting or political” behind the app’s disappearance from the App Store and that it will return shortly.) You can ask these questions for ages, and they’re all fair, but it might be simpler to conclude that this is how the App Store works: a series of poorly-worded policies that are usually used to steer games away from hot-button issues and that tend to overreact when the political climate gets heated.

Are games, as Abueideh suggests Apple sees them, inherently apolitical? No. Moving on.

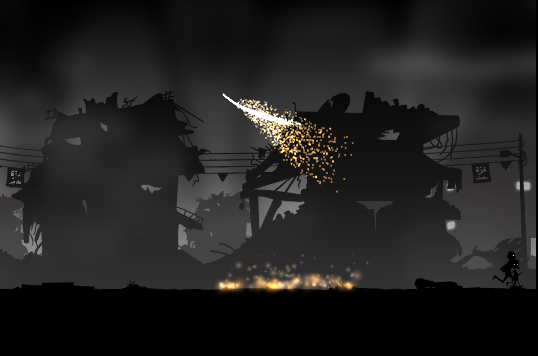

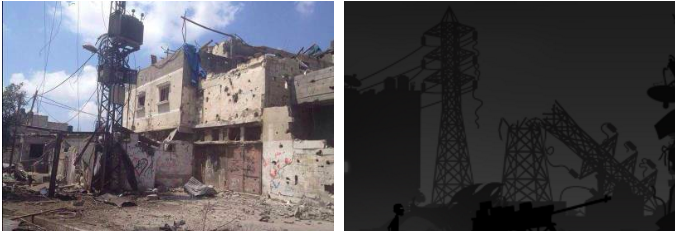

The more salient point regarding the Liyla debacle is that life is political, whether we like it or not. Plenty of people would love to lead largely apolitical lives, but that is luxury few can ever access. In a curious way, then, Apple, through its ham-fistedness, has upheld many of the thematic elements of Liyla that prevent it from being listed as a game. Liyla is the story of a 14-year-old girl stuck in the middle of the Israeli-Gaza war. The images released by the developer show shelled buildings, rockets, and military vehicles based on actual events. Abueideh has shown these images side-by-side with footage from the conflict and the resemblance is striking. Reality, whether Apple likes it or not, is political. If you lived in Gaza at this (or any) time—even as a 14-year-old girl—your existence, even the games you played, could not be divorced from politics. There are plenty of people who would like to escape politics and its consequences, but for those living outside Apple’s walled garden that is not a viable possibility.

We ask too much of the oppressed: We ask that they not resort to anger or violence; we ask for more and more proof; we ask for shows of patience. The demand to not be too political is just another entry in this series of asymmetrical requests: your existence is wrapped up in politics, but never say as much. These are all impossible demands, but they are made nonetheless and derogation has its consequences. To ask someone to be less political is, in many cases, to ask them to accept the status quo. Liyla, as best I can tell, is not a hugely radical work, but it is political because that is unavoidable. We ask for a lot, but we cannot ask humans who make games or the characters who figure in games, to be apolitical.

You can download Liyla and The Shadows of War on Google Play.