Dust off those MFAs. 19th century masters come to life in "artist simulation" game.

“Bonjour! I’m Édouard Manet,” a textured portrait of the pivotal French painter greets me when I start playing Avant-Garde. The painting is Manet’s Autoportrait à la palette, one of his best-known late works as an Impressionist, after he had made the gradual transition from Realism.

Behind Manet is a scene of Paris in the rain, at the Place de Dublin, near the Gare St-Lazare, where gadabouts in top hats stroll with lady-friends under black umbrellas. Though the scene has been animated with the drizzle of rain, students of art history will recognize it as Gustave Caillebotte’s photorealistic Paris Street; Rainy Day.

In Avant-Garde, an artist simulation game, you play as a no-name contemporary of 19th and early 20th century masters, rubbing shoulders with the likes of Cézanne, being sharply criticized by the snide Bouguereau, forming manifestos with Weingärtner over fizzes and slings. You can think of it as Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris as a videogame, but set a half of a century earlier, with more painters and no Fitzgerald or Hemingway. The player stands in as the silent protagonist, which, depending on your predisposition for Owen Wilson, could be a good thing.

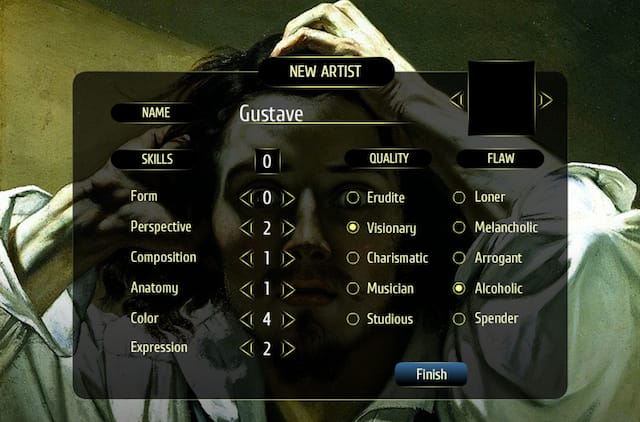

Are his hands clinched in madness because he’s an alcoholic, a visionary, melancholic, or…

Still in alpha, but already a lot of fun, this wistful jaunt to the Salon de Paris is the classy creation of Lucas Molina, a history student who is making the game for his master’s thesis, in order to illustrate the conflict between realism and modernism. As a work of the imagination, it also demonstrates a shift in ethos between the Victorian era and the internet age. As seen in the sample, the meme, the remake, and the reunion tour, there has been an uptick in the mooching of creativity.

But its not all bad. As Avant-Garde proves, repurposing creative works creatively can be a very good thing. Aside from the menus and the rain and the piano, little if any original assets make it into the game. The art is on loan from artists, care of the public domain. “All of the portraits are self-portraits,” Lucas says, “even Picasso’s, though such realism may not look like his style. It’s a portrait of when he was still young and not yet avant-garde.” Lucas’s girlfriend told him the realist one fit the setting more, probably because it’s a close copy.

The best support for copying is perhaps found at the character creation screen, where the backdrop is the unnerved countenance of Gustave Courbet, from his self-portrait The Desperate Man. This is where you invest skill points into attributes and choose your disposition. But it’s more than a simple numbers game, suggesting additional dimensions of interpretation about the painter’s source of torment. Are his hands clinched in madness because he’s an alcoholic, a visionary, melancholic, or is he struggling with his skills?

From there, on your way to becoming a modern master, you can specialize in pencil, ink, charcoal, watercolor, gouache, oil, plaster, marble, and bronze, but Lucas, who began seriously practicing as an artist five years ago, at the age of eighteen, prefers the convenience of painting with a Wacom digital tablet. (“There’s no Ctrl+Z in real life!” he tells me.) When I asked him how he would rate himself as a painter, using the character creation tool in his game, he broke it down:

Form: 3

Perspective: 1.

Composition: 2.

Anatomy: 1.

Color: 3.

Expression: 0

None too shabby. But in reference to the goose-egg next to the Expression stat, Lucas apologizes. “My paintings are usually copies of something. Those studies allow you to understand form and so on, but they also kill your creativity. I actually put that in the game: If all you do is make copies, you’ll never be a creative painter because you’ll lose in expression. You need to be imaginative.”

I’d disagree. If there’s anything Avant-Garde shows us, it’s that there are plenty of ways to be inventive while copying things.