It’s best to play this roguelike the same way you’d read The Grapes of Wrath

Have you read The Grapes of Wrath? If you’ve been through the American school system you probably just hissed through your teeth at the sight of its title. For bringing up those aching memories, I apologize. But if you did study it, you’ll be familiar with how John Steinbeck structured the chapters throughout the book.

All the even-numbered chapters follow the journey of the Joad family as they travel from Oklahoma to California in search of work, trapped in the Dust Bowl, subject to death and dehydration. On the other hand, the odd-numbered chapters are considered “intercalcary.” In these, Steinbeck zooms out from the Joads and brings in the wider historical context, connecting the family’s plight to the novel’s wider humanist themes, and analyzing the troubled political and social structures of America at the time.

heading on a journey into the unknown

This juxtaposition between the chapters in The Grapes of Wrath is how I believe I have been playing Caves of Qud. It’s a roguelike, and what some might deem a ‘proper’ one, as it’s far away from the more common action-hybrids you see the term “roguelike” being hung from these days, and much closer to the games that the term was originally applied to (i.e. Rogue).

To give you some context: Caves of Qud is set in a post-apocalyptic land called Qud, it belonging to a terrible future vision of Earth in which most of our technological advances have been lost. It’s a jungle-like area that is bordered by a salt desert and large mountain ranges. Mostly, it’s a terrible place to be, and a worse place to live, yet there are those that do. People also travel to Qud in their droves as, inside its ancient caverns and temples, can be found valuable lost technology. There is also an ancient evil arising from these caverns but we don’t have to be concerned with that right now.

In the game, the land of Qud is represented from a top-down perspective, and while it doesn’t adopt the basic ASCII-style of many roguelikes, its limited graphics feel like a throwback to it. The point being that when you’re looking at the screen you can’t immediately read everything that is on it unless you recognize the symbols and know what they represent. Another salient point is that when moving across the land, you do so a screen at a time, which gives you four different directions to travel in, and each screen you travel into is procedurally generated as you enter.

Being set in what is essentially a jungle, there are plenty of strange and hostile creatures in Qud, and it’s possible to meet many of them right at the start, making it dangerous to move around, each step forward potentially determining your character’s point of death. As you play the game, you’re heading on a journey into the unknown, and this is where the analogy slips in: this moment-to-moment decision making is the narrative chapters of The Grapes of Wrath—we guide a character around, as close to them as we are the Joads in Steinbeck’s novel.

a sense of magnificent history to dredge from its depths

However, considering how unpredictable Caves of Qud can be, and how tricky its screens can be to read at first, it’s vital that you spend some time to assess your environment thoroughly in order to avoid unnecessary conflicts. To this end, the creators of Caves of Qud have supplied a look function. It’s tied to the ‘L’ key, and when pressed, you can select certain tiles on the screen and read a description of whatever it contains—be it enemy, friendly, plant, or mineral.

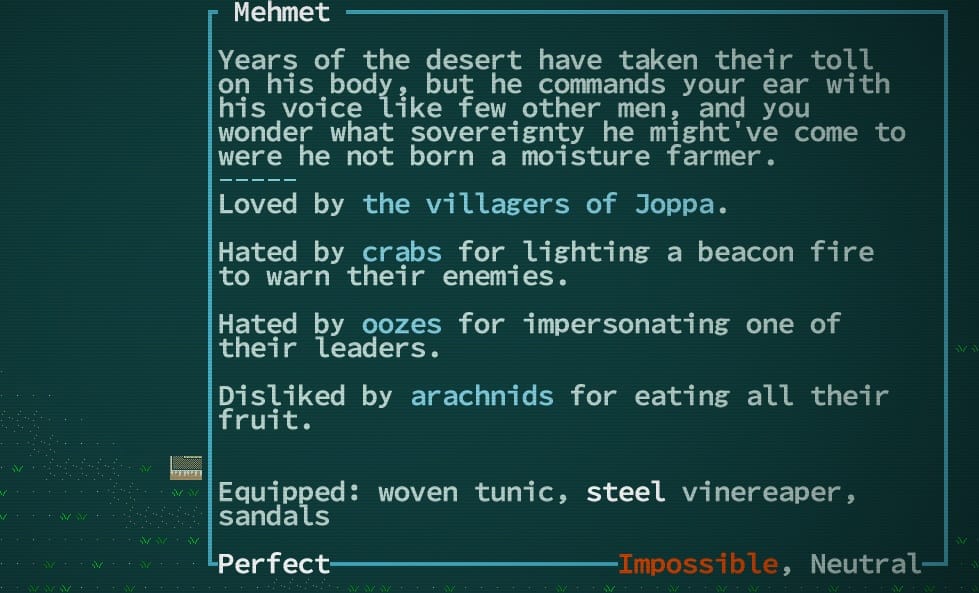

But the descriptions in Caves of Qud are more than your typical fantasy world padding. By reading a description of something as insignificant as a plant you can acquire a sense of the place’s politics and its people. As an example, read the following description of Mehmet, the first person you talk to in Caves of Qud, and note how class politics is suggested through the man’s potential: “Years of the desert have taken their toll on his body, but he commands your ear with his voice like few other men, and you wonder what sovereignty he might’ve come to were he not born a moisture farmer.” Mehmet is also wonderfully given a random set of three relationships with the creatures of Qud, as you can see in the screenshot below, underneath the standard “Loved by the villagers of Joppa.”

Returning to the analogy, looking around the screens and reading these descriptions is akin to the intercalcary chapters in The Grapes of Wrath. And if I were to really indulge this line of thinking, I’d say that there was a similarity in how Steinbeck talks about the land and its soil in The Grapes of Wrath, and how Qud is treated as a character itself in the game. Steinbeck does this as, to the farmers, the land was an organ or a body that had to be tended, treated, and sown; maintained so that they could live off it. In Caves of Qud, there are farmers that have the same relationship with the land, but further than that, there are layers of ancient civilizations buried in Qud’s land, and so there’s a sense of magnificent history to dredge from its depths, not to mention the characterization it gets from housing an evil.

Remarkably, you get a sense of all this in the first screen of Caves of Qud, which is probably the only screen in the entire game that remains the same every time you start over. What is established in this first screen is of high importance as it sets the tone for the rest of the journey. But also, as this is a roguelike with permadeath (meaning that, when you die, you have to restart everything), the first screen is the one you’re going to see the most.

A mini stratum of people is set-up in this first screen for you to consider, focusing on their apparel, behaviour, and the condition of their skin and limbs. The farmers are men with “gnarled hands,” hot with sweat and with tatters slung around their necks. The religious zealot is said to have “precious saliva” flying from his cracked lips as he preaches around the farmers. Further up, the warden holds a “purring blade” in one hand while the other is “lame and frostbitten,” apparently to demonstrate how nature doesn’t care for a man’s position. And the elder is a “hunched-back ancient” with a warm smile and with eyes in the palms of his hands.

Through the illustrative writing in Caves of Qud you’re able to get an inescapable impression of the place simply by taking the time to look. Not just of your immediate surroundings, but of the systems that drive the people around you, giving you an instinctual understanding of how this fantasy world works, which will probably come in handy later on. As Steinbeck pulled back to get a wider picture of what was happening to the Joads, beyond their control, so must we while venturing into the rough jungles of Qud, for we won’t otherwise be able to understand and prevent our repeated deaths.

You can purchase Caves of Qud on Steam. It’s currently in Early Access.