Bohemian Killing explores our muddy legal systems

I sat in court as a member of the jury this past summer and found it disappointing. I’d been spoiled by the dramatized murder trials and the heart-tugging sociopolitical conflicts in the fictional courtrooms of 12 Angry Men, To Kill A Mockingbird, and A Few Good Men. The verdicts were obvious, there was no shouting or revelatory speeches to be made, no drama; one of the defendants failed to turn up, and so was judged entirely on the prosecutor’s argument, sentenced in less than 10 minutes.

It wasn’t until I had spent those two weeks in and out of court myself that the rich theater of the courtroom drama became so obvious. Most trials are dull and petty in real life, concerning what would otherwise be an insignificant accident, or at most a short-lived inconvenience. You have to sit through the demeaning confessions of a middle-aged layabout who heard a bump on a Saturday night. You watch as he’s grilled by a trained lawyer on the precise time he got up from his sofa to empty his bladder during his otherwise uneventful evening.

“I also have a certificate in interrogating suspects and witnesses using FBI methods”

It is essential, then, for authors to spruce up the courtroom drama, to give it a frilly hat and a bad attitude in order to hold the attention of their audience. In fiction, lawyers must be alcoholics, witnesses traumatized or outright liars, and defendants have to snarl in silence with a murderous gaze. Plot twists and rivalries are the paprika and chipotle powder to the bland courtroom soup.

This extrapolation works in novels, films, and it also works in videogames, hence why Capcom’s Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney series is so overstated and camp. Accusations are made with huge pointing fingers, while objections are given a comic book’s flair with iconic onomatopoeic punchiness. It’s as far away as you can get from what sitting through an actual court case is like while working within its format. The lesson here is that what you shouldn’t do when attempting to turn courtroom drama into a videogame is try to make it true to real life. Unless, that is, you want your game to be utterly dull, in which case, go for it. But you try telling Marcin Makaj that; he’s of the thinking that his “realistic” courtroom drama game Bohemian Killing (currently on Indiegogo) is the exception to this rule.

Makaj is a Polish lawyer who passed his exams earlier this year, and will soon take his national exam to become a full-fledged legal practitioner. “I specialize in Polish criminal law, and in criminal profiling (I have a certificate in this), I also have a certificate in interrogating suspects and witnesses using FBI methods,” Makaj said. So Makaj is wise to the reality of courtrooms, certainly wiser than me, and aims to bring in his knowledge and experience to the game’s design. But he’s also taking from the 2000 film Under Suspicion, at least structurally, to avoid the insipid proceedings of non-fictional courtrooms in Bohemian Killing. In Under Suspicion, Gene Hackman’s character Henry Hearst finds a raped and murdered young girl, and when recounting the events surrounding this he constantly changes his story. In Makaj’s Bohemian Killing, you essentially play the Gene Hackman character, in this case named Alfred Ethon, and can also swap the details around when giving your side of the story in front of the wigs.

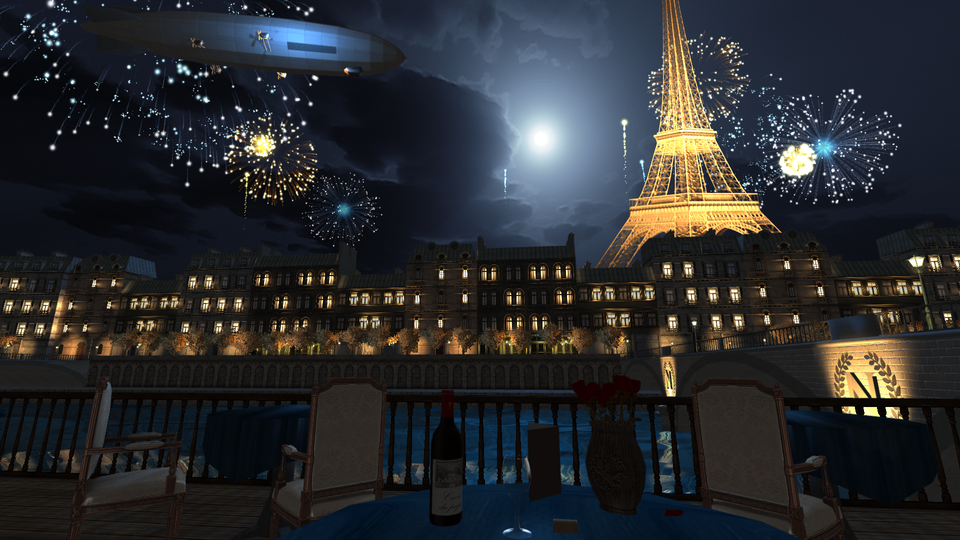

But you don’t do this by, say, selecting passages of texts; you do this during first-person flashback sequences by making decisions on the spot. Makaj’s trick is to take the (in)action out of the courtroom, and into the other scenes being referred to in the testimonies. When you stand for questioning, you’ll be prompted to tell your story by explaining to the court what you were doing on a certain day and time. In these moments, you’re whisked away to the riverside restaurants, hotels, and apartments of 19th century Paris. The decisions you make and actions you perform in these scenes affect your statements in the courtroom, operating in a similar way to how the Narrator reacts on-the-fly to the player’s movements and actions in Bastion.

the outcome of the polygraph will be based on your heart rate.

The judge may ask you, “What were you doing at 9 o’clock on the night of the murder?” At which point you will reply by stating that you had returned from your friend’s house and were going home. At this point, the flashback kicks in, and you find yourself in a first-person perspective in front of your house. Here, you’re free to do as you wish. If you walk down the street you will tell the court that you thought it was a pleasant enough evening for a walk. And if you enter your house then this will also be reflected in the narration.

Makaj walked me through a better example of how the interaction between the flashbacks and the proceedings in court goes:

“A neighbor testified that, at approximately 10pm, he passed you in the entrance of the tenement house, noticing that your clothes were covered in blood. You can try testifying that your neighbor is lying and prove to the court that he has a reason to do so. Or, maybe, you’ll get into a bar fight just a few minutes before 10pm so that you can testify that the blood the neighbor saw was yours, and not the victim’s. Another option would be to cut yourself while shaving, covering your clothes with blood when the neighbor sees you later. But what if the court finds your time of shaving conspicuous and torments you with even more questions? How will you get out of this? How does this work in practice?”

Adding more options, or perhaps restrictions in some cases, to how you testify in court is the fact that these flashback sequences run in real-time. If 10pm passes while you’re in the flashback in Makaj’s example and you don’t meet the neighbor in the entrance of the house, then Ethon will testify that they’re lying about the entire meeting. You can also meet the neighbor with no blood on your clothes at all to object to that specific detail in their story. Each flashback has a number of opportunities for you to twist how you testify, whether it’s in favor or against the charges placed upon you. Some of these involve getting Ethon drunk, or tired, or raising suspicion in those who happen to see him walking about that night. Makaj also has the idea of using chest straps and watches—specifically, the Wahoo BlueHR, and Mio Alpha watch—which support bluetooth, so that while you’re being interrogated the outcome of the polygraph will be based on your heart rate.

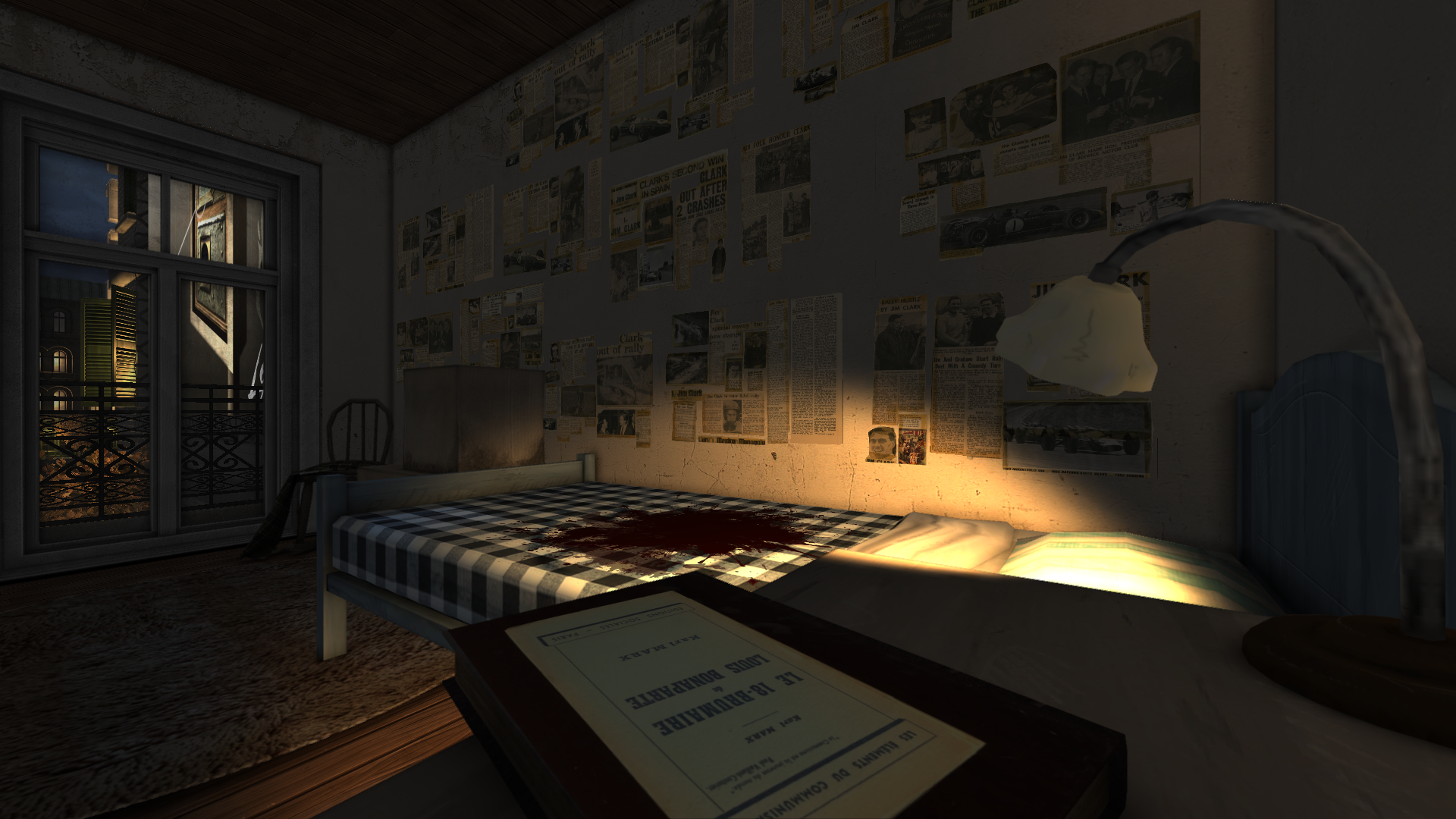

That’s about as far as the comparison to Under Suspicion goes, as what sets Bohemian Killing apart from the film, aside from the obvious, is that you know from the start that you committed the murder. In fact, the game’s tutorial involves you killing the victim. Alfred Ethon is guilty of what he’s being trialled for, no doubt about it. What you don’t know is why he killed this woman, who was “a maid working for an impoverished Lord, a relic of the old French regime”. This is where Makaj finds further intrigue in Bohemian Killing, as while trying to present yourself as either guilty or innocent, you’re still working out what your motivation was, which leaves you in a grey area: what if you had a good reason to kill her and get away with it? You research this motive through exploring the various possibilities in each flashback sequence. More information can be found in studying the witness statements, forensics, and profiles of those involved in the court case. Taking all of this into account may lead you to find the grander plot hidden away in the game. It’s one that Makaj teases contains many a reference to the myth of Prometheus, and has you mixing in among the racial tensions, political mishaps, and class wars of 19th century Paris.

The Dreyfus affair is an interesting line for Makaj to draw

To ensure that this background plot in Bohemian Killing is muted rather than obvious, but also not impossible to discover, Makaj is investing in environmental storytelling. He’s paying a great deal of attention to the finer details of his recreation of various Parisian locales. For this, he has been using his sister, Marta Makaj, as a consultant for she is a model currently based in Paris, and therefore able to mix in with the city’s current patricians. “I want to create this special, classy style of Paris—especially Paris at night. There are elegant people, very realistic French food (you can eat and drink in the flashbacks), French posters, ads, etc,” Makaj said.

Beyond putting in clues for the player to pick up, Makaj is also contextualizing the Paris setting and its time period by including sights that would be common at the time. “One of the biggest Paris companies introduced food vendors, where you can buy fresh food from your own house (and you can actually do this during the game). And outside you’ll be able to see a lot of local shops closed due to bankruptcy,” Makaj told me. There will also be strikes and protests in the factories, some of which belong to the character you embody, who I’m told has a gypsy origin but has found his fortune as an inventor. This wealth has allowed the main character to mix in with the same circles as old lords from rich houses that are “very rude to him” due to his family background. Discovering the personal history of Ethon and the relationships he juggles is all part of piecing together the full story.

Interestingly, Makaj is also working in references to the infamous Dreyfus affair; the political scandal that ran from about 1864 to 1906 as Captain Alfred Dreyfus, who was accused of leaking French military secrets to the German Embassy, was put on trial. The Dreyfus affair is an interesting line for Makaj to draw, as it not only divided the whole of France, but also brought into question the reliability of the courts. It being present in the game, if only in passing, means that the upholders of the law who sit in the court may have reason to be less hasty in their judgement—they’re being eagle-eyed watch by the media and public. Perhaps this is what gives you the opportunity to mess with your story so much in the first place.

Considering the enormous effort that’s going into working in historical context into Bohemian Killing, it may come as a surprise to find out that its recreation of Paris contains many steampunk designs. Makaj has been lured by Villemard’s 1910 postcards that famously envision life in the then-distant year of 2000. It’s a vision of the future from someone who witnessed the industrial revolution, and so it is dominated by primitive-looking machines used for every purpose. Firemen have wings strapped to their backs, negating the need of ladders to douse apartments with water; wooden planes are the main mode of transport; books are fed into a machine that transposes the knowledge within to students through cables and earphones.

Makaj trusts that as long as he keeps this tangential fantasy element as believable and consistent as the rest of the game then he can get away with it. But we’ll be the ones to judge that. In any case, I prefer it over having to do jury duty again.

You can support Marcin Makaj in creating Bohemian Killing over on Indiegogo.