I thought I was getting pretty good at Hokra—until the Brazilians showed up.

In what is not an altogether unlikely scenario around the Singapore-MIT GAMBIT Game Lab, a dozen or so 20-something Brazilian men showed up in our lounge. As it so happened that day, a few of us were playing what is my new sports videogame obsession, Ramiro Corbetta’s Hokra.

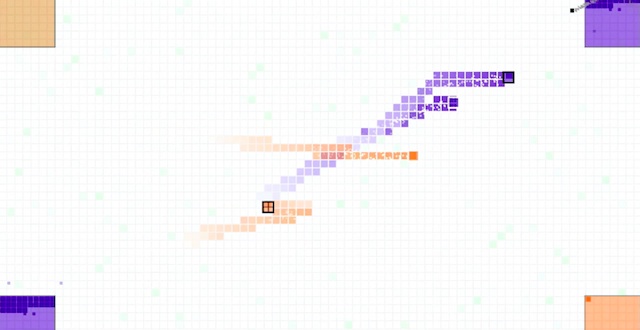

Hokra is something akin to FIFA or NHL, but different. Commissioned for and debuted at the 2011 No Quarter exhibition, it is a top-down, minimalist videogame inspired by soccer, in which two teams of two manipulate squares to try and move a ball into one of two scoring corners. While the puck is in a team’s scoring corner they rack up points, and when the appropriate number of points are scored a team wins. You can pass the puck from player to player by depressing the “A” button on an Xbox 360 controller (the game is developed using Microsoft’s XNA game studio). Naturally, the other team tries to tackle you, steal your passes, and score in its own corners. Games last approximately five minutes.

Hokra invokes the simple beauty of soccer. There is the minimalist aesthetic, on the one hand: the floating blue and orange squares, the glassy white pulsing field, and the simple black tailing “ball.” But it’s the simple minimal interaction of the game that underlies its beautiful design. Hokra is fundamentally a one-button game. You pass, shoot, dribble, and kick with the “A” button. A similar simplicity forms the foundation of soccer: all you do, with the exception of the goalkeeper, is kick. When you are not kicking, you are moving to prepare to kick, strategizing with positioning. Elite players kick very well, and in many different ways.

Around the lab you can tell when we’ve fired up Hokra because of the yelling. People grin like idiots, grimace while hammering on the controller, and scream ebullient victory or agonize in defeat. Everyone tends to congregate upon hearing the din, and the intensity of matchups tends to grow as the play session goes on.

The young Brazilian men were reluctant at first, being new acquaintances, but a couple of players decided to give the game a go. The drubbing that ensued was incredible. They played differently. They passed. They moved without the puck. They communicated with one another. I sat there, a loser, the cord of my controller like a tail between my legs. My pride bruised and my competitive spirit awakened, I determined then to be better—to get better.

The goals and mechanics are simple—move the puck to the corner before they do—but Hokra is deceptively complex. Its appearance belies a depth that emerges from the interplay of the teams, the layout of the play space, and the coordination of the sprint/tackle/pass mechanics all being mapped to one button. As Frank Lantz mentions in the game’s video trailer, Hokra demands “a lot of skill, and a lot of nuance.”

I have wondered what makes Hokra a “sports” game. It is different from the likes of NBA 2K or Maddenin not representing a known sport. Hokra is something new. It is hockey, soccer, and Mondrian. It invites strategic depth, and rewards technique and grace. It frustrates you with loss, and heartens you with victory. These are all excellent game-design qualities, and they are not exclusive to things we might deem “sports.” So why is Hokra a sports game?

It’s because of how I have seen Hokra played. It is not, in fact, the challenge, the skill, the technique, or the mechanics that make the game sporty—no, it is the screaming and the jeering, the physical and digital jostling, the wringing of hands and the gritting of teeth, the spectating and the communicating. Shout, jeer, jostle, grimace, chant, cheer, root; these are the verbs that make Hokra a sports game—not pass, shoot, or score. It’s worth invoking Stanley Fish here to ask, “How do you recognize a sports videogame when you see it?” I suppose I’m saying Fish is right. We see it because we are part of an interpretive community that looks for it, the boundaries of that community unknown. We frame our experience of a game like Hokra with the trappings of sport-like expectation.

I’m not sure what compels people to play the way they do. I suspect the factors are myriad, and messy. But I have no doubt that Corbetta’s stated intention as author—to design a “sports” game inspired by FIFA—affects how we players engage the game. Something ramps up our competitive spirit when we play Hokra at the lab. Our matches grow louder when our Austrian colleague joins in. I have played a lot of sports, and I have played many so-called sports videogames; and something in Hokra, in the entirety of the performance—from spectator, to player, to blog post, to magazine column—screams sports, as I sometimes scream in defeat.

I have been training. I don’t know when I will ever get to Rio, but when I get there, I’ll be bringing Hokra with me.

Boomshakalaka! explores the intersection of sports culture and videogame culture. Abe Stein is a researcher at the Singapore-MIT GAMBIT Game Lab and a graduate student in Comparative Media Studies at MIT. He studies sports videogames and their players, and blogs at A Simpler Creature.

[By the way, you can play Hokra at our San Francisco party! —Ed.]