In pursuit of videogames’ bottomless pits

There’s hidden treasure inside every videogame if you know how to look for it. It’s not mineral and it certainly isn’t economic. Yet, nearly every virtual world has it locked away, forbidden, never to be seen. What am I on about? It’s a comfortable freefall into nothingness. The serendipitous void at the edge of the world.

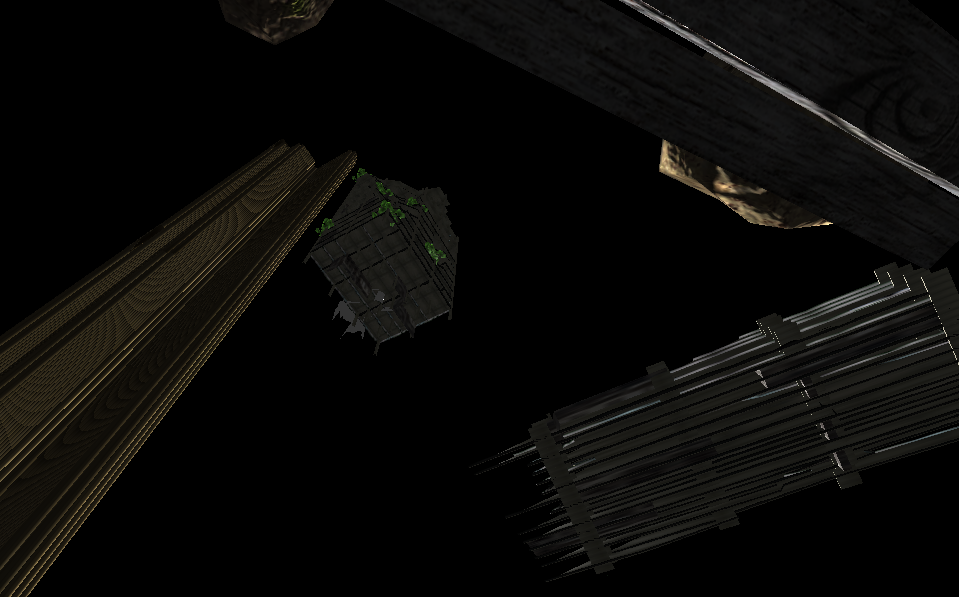

falling like angels from the virtual heavens.

As you probably know, it’s common practice to have a fail-safe to ensure that the contours of a game world are impenetrable. This is an effort to render the coveted void inaccessible. Usually, colliders disguised as buildings or giant walls that don’t let the player pass are enough. Other tricks include Mario Kart‘s Lakitu, who rides a cloud and hoists you up with a fishing rod, kart and all, to place you back on the track when you fall off it. More common in 2D platformers is using a death trigger around the edges of the screen. If the player falls or wanders too far in one direction, they’re killed outright, being reset to the last checkpoint they reached.

But there are exploits to bypass these obstacles. These are the keys to the treasure. Those that seek it have gathered around a Tumblr blog titled “Bottomless Pits in Games“. Here, they contribute screenshots of their time falling like angels from the virtual heavens. Usually, these shots are of frozen stares upwards at the artificial 3D structures they once stood upon. It’s a snapshot of a victory won by treating each virtual world as an apparatus to be broken.

Sergio Cornaga, a game creator and curator, is one of the regular contributors to the blog. “I view finding bottomless pits as a challenge,” he tells me. “After playing so many Unity games, I realized it’s often possible to slowly climb walls with repeated jumping. Often this leads to bottomless pits, or other areas the developer didn’t intend to be accessible.”

The thrill of this is a simple one that most of us would have felt when being disobedient for the first time. Through the game’s architectural structure you are told where you are allowed to go. Stepping beyond those limits is sticking up a middle finger to those rules. That feels exciting, perhaps a bit naughty, and we like that. We want to repeat that.

the mystical other places that are supposed to be unseen.

Cornaga is far from the only one who approaches games with these intentions. Neither is it only amateur productions that are vulnerable to these anarchic pursuits. As Cornaga points out to me, there are those that seek the “Far Lands” of Minecraft, which are strange multiple layers of pitch black soil found only at the edges of the supposedly infinite worlds of the pre-1.8 versions of the game. There are also those that have created guides to glitching through the walls in thatgamecompany’s Journey; toward the mystical other places that are supposed to be unseen. And then there’s the troupe of forum gossipers still trying to unearth the secrets contained within Shadow of the Colossus, held painfully just out of reach.

So it’s more than a rebellious sport, all this overstepping, there are discoveries to be made that reveal processes into a game’s creation, abandoned ideas stuffed away to be forgotten, and empty stretches of land from where you can admire the sky box. It’s this pursuit that Cornaga coined “glitchhiking” in his own fan page devoted to exploring the glitches in the game lisa.

Another regular contributor to Bottomless Pits in Games, Clyde, attests to the same appeal. “The first time I saw Bottomless Pits In Games it was one of those moments when I realized that a default decision of best practices that I never questioned, is actually removing an exploratory method of appreciating the work.”

“certain inclines become invisible and everything floats away.”

What Clyde goes on to describe is an esoteric beauty found only in moments when falling away from the world altogether. He recalls being able to pinpoint the edge of a game’s world and turning around to the consider the angle from which he will view his descent. Clyde considers it a technique that he’s developing to both gain access to the bottomless pit and to take pertinent photos when in freefall inside of it.

“Just by collecting photos and animated gifs of these moments in games, Bottomless Pits In Games changes it from this crazy thing that happened once or twice into a treasure-hunting hobby. A couple of times I’ve seen something pop up on there and it made me go back to the game to see if I can find the exit. Once I see that someone else has done it, I want to see it for myself,” he says.

Mapping out this uncharted territory and sharing it with each other is what seems to have drawn the contributors of Bottomless Pits in Games together. And it’s in this that their unusual passion is not so dissimilar to that of an explorer, or a wildlife photographer, or those who hunt for UFOs in the night sky. Indeed, Cornaga says that he finds bottomless pits “visually rewarding due to the way certain inclines become invisible and everything floats away.”

The founder of the Bottomless Pits blog, Noyb, agrees with this notion. He told me that the reason he felt compelled to document his times endlessly falling through the infinite expanses of videogames is due to the uniqueness of the experience. “Seeing the world from below and finding appealing geometric structures, a better understanding of the level’s topography, intentional secrets placed by the developer or vestigial forms they assumed no one would ever see,” Noyb says, outlining his fascination.

“a better understanding of the level’s topography”

Noyb’s interest in bottomless pits in games can be traced to thecatamites’s farcical edutainment game Pleasuredomes of Kubla Khan. In it, you are rewarded for jumping off the level with hidden dialog from the narrator, who becomes furious at your attempt to subvert their teachings. “I never would have thought to perform that action myself, so both the suggestion from another player to jump off the level, and thecatamites’ recognition and legitimization of this behavior stuck in my mind every time I played a small Unity game set in a 3D space,” Noyb told me.

Further cultivation came a year later when playing Rylie James Thomas’s 100 Free Assets, which is an infinite void in which 100 free assets from the Unity Store are placed, floating in nothingness without order. Another is Juliette Porée’s Cyborg Mountain, which is a first-person exploration game in which one of the cyborgs you seek is hidden underneath the mountain, visible only to those who fall beneath the game world.

After playing these games and tracing similarities between them, Noyb started the blog. The fascination, he says, is in how these games “embrace the idea that nothing exists beyond the game’s borders—something most games try their best to hide—and the repeated image of the world from below.”

None of what the contributors to Bottomless Pits in Games invalidates, harms, or otherwise discredits the videogames that they slip through. It’s an innocuous pursuit, a kind of cultish enthusiasm: a different way to approach virtual worlds, to look at them, admire them, to make sense of them. Willingly falling into the void like this is a daring enactment; a dive into the “what if?” without a safety cord. Sometimes, those who take the plunge have their curiosity spoken to, a rare treat traced in the infinite. Most the time they only fall, fall and fall, carefree of death, danger, and responsibility. They tilt their heads back and happily watch everything disappear from view, at ease at last.