The brilliant clumsiness of Grow Up

There’s a blinking emoticon of a robot waving its arms around. It has the kind of joy that should be reserved for kids at a birthday party, not a loading screen.

Once the bar is filled the robot appears again—now in full 3D, a red shell like a Lego brick—but this time it’s animated like a drunk who’s too inebriated to stand. When I push forward on the analog stick it’s as if my small motion has turned the entire planet under its feet. The robot’s arms flail as if reaching for a pole or an edge to cling to. When it walks, it leads with its wobbly head, the rest of its body trying to keep up as if awaiting the tug of a puppet string, each foot a threat to each other as they blindly scramble for the floor. The giant ladybugs nearby quiver in concern.

The robot’s name is BUD. Every movement of BUD’s is an effort of visible labor. Even turning around on the spot seems to require the force of a tornado—it’s as unpredictable as one, too. Given how clumsy BUD is it seems right that he refuses to face me. I’d be embarrassed, too. I try to turn his head towards the camera but it appears to be sat on the neck of an owl. Probably for the best; you’re a total wally, BUD, and I’d only make that known.

BUD is the inglorious winner here

BUD might be the daftest character left to your control in a videogame. Other contenders include Octodad, but his slipperiness made sense; he wasn’t daft, he was an octopus trying his best to fit into human society. There’s also Mario in those moments when he’s running atop a bumper ball—the momentum just within the bounds of your control—but again, any foolishness isn’t characteristic of Mario as it is the situation he’s in. No, BUD is the inglorious winner here—he’s got no excuse for his failure.

In truth, he doesn’t belong in a videogame. He’s better suited to a Looney Tunes animation. When Bugs Bunny or Elmer Fudd are running at speed but need to halt or change direction, they kick both heels into the ground, clouds fuming from the floor due to the friction. BUD applies a similar logic to overcome any given velocity you fling at him. But he hasn’t mastered the technique that Chuck Jones gave his characters, so when he flies across a surface and you suddenly pull back on the stick, his legs turn into ferris wheels and his whole body slants uncontrollably. Sometimes this fails, and he crashes into the stalk of an enormous mushroom—that’s when BUD performs his tribute to the Transformers, going from a robot to a car wreck in a second flat.

The goal in Grow Up is to climb to the moon. That is … ambitious. Have you seen how BUD stumbles? He doesn’t need to be on the edge of a thousand-foot drop to teeter—he does that with every step. If anyone is fit to make like Jack and clamber up a beanstalk it is not BUD. Don’t put his name down. Don’t bother. Yet it is precisely this ineptitude that makes the game work. Compare BUD to Lara Croft or Nathan Drake and it makes sense. Those two heroes of the vertical ascent are graced with too much skill. It means that, when you cling with them to a cliff edge, their capable one-handed leaps between grips might as well be automated. You point them in the right direction and let them go. No matter how many times Drake slips, or the number of falling boulders Lara evades, the peril of the climb is glaringly artificial. You feel safe in their bodies at any height, any angle.

It is a very different experience with BUD. When climbing, you have to use the left and right triggers to control each respective metal hand. A synthesis between you and this clumsy robot is created as you both clamp down with your fingers; you to a controller, him to a sturdy plant. As he thrusts his little claws in whatever direction you’re pointing the camera, and the stalks he climbs curve and spiral, it is entirely possible to fail to find purchase. And when he falls you both fall. It then becomes a desperate scrabble to get hold of some lower point, frantically pulling on the triggers, his hands pinching at the open air. There are more reasons these moments feel so dangerous. One of them is the spontaneity of the game’s world: at any point during your fall you could accidentally grab a loose rock, suddenly plummeting again. But bigger than that is the possibility of free falling all the way from the highest point in the game to the lowest—compare that to Uncharted, in which Nathan Drake simply expires in mid-air after falling a certain distance. That, paired with the fact that the game won’t reset you after a safe landing, no matter the height, means any significant drop needs to be followed by a duplicate climb, unless you managed to activate a teleporter before you fell. Grow Up may may have a childish demeanor but, unlike other modern platformers, it’s not playing pretend.

the hang glider is simultaneously the best and the worst

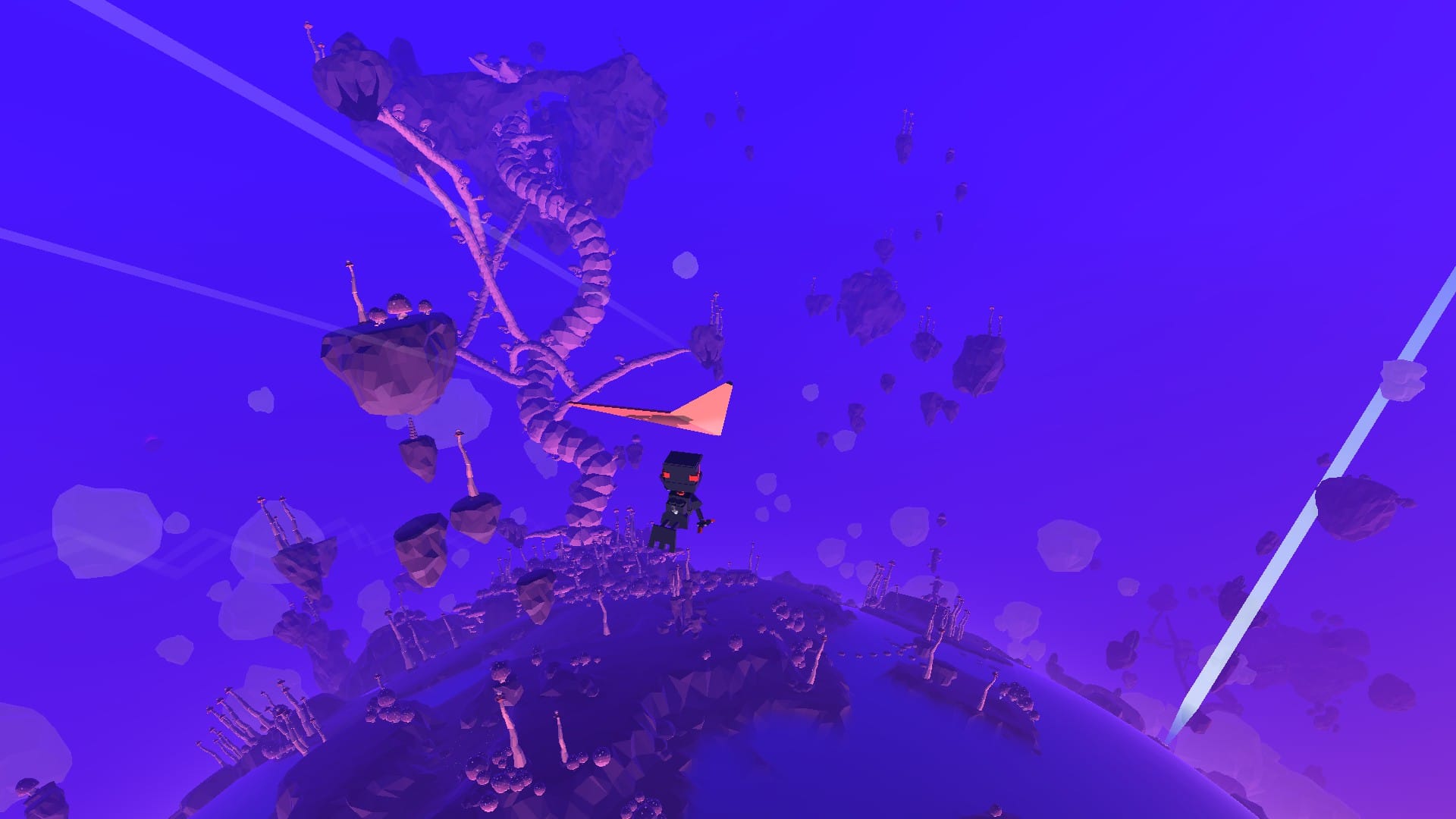

What Grow Up achieves is to put the manual labor back into climbing to a height. And in doing that it allows room for expression. Legendary Polish rock climber Wojciech Kurtyka once remarked that mountaineering interweaves “elements of sport, art, and mysticism,” and that what determines one’s success in it “depends on the ebb and flow of immense inspiration.” Grow Up, at its best, follows these words as if a guide to making a game about climbing. This is partly achieved by expanding the game’s playground to the size of an entire planet, whereas BUD’s previous outing in Grow Home (2014) was confined to a series of floating islands. Crucially, you are given little direction as to how to negotiate this planet. The most you get is POD (Planetary Observation Droid), a satellite that gives you a bird’s-eye-view of the globe, showing you areas of interest: the ship parts BUD needs to recover, challenge areas, collectable crystals, and new abilities. With that, you are left to find your own moments of “immense inspiration.”

You might see a large island floating near the top of the planet’s hemisphere and decide that, no matter what, you will climb up to it. BUD’s unsure footing be damned. Not only is such a directive possible, Grow Up lets you determine your own path upwards: that manifests in the hand-to-surface actions, but also in where you throw seeds to grow springy plants that thrust BUD towards the sky, and how you can steer the shoots of Starflowers—the biggest bioforms in the game—as they grow rapidly like green limbs, BUD holding on as if it were a rodeo. It leads to moments of genuine beauty as you climb a steep rock face, driven solely by your own determination, and see small bug families scuttle past you, the distant sun kissing your view from up high with a glorious tangerine zest. Grow Up’s dedication to scalable verticality is all part of the thrill.

Its mistake is in adhering to the ostensible demands of making a videogame sequel. Grow Home had a simple purity to it—you were a robot, it could climb, and so it did, all the way up to space. Grow Up repeats this journey but steadily turns BUD into Inspector Gadget as you complete its trials. Of all the new abilities, the hang glider is simultaneously the best and the worst. Once unlocked, it allows you to swoop across the biomes with ease, jumping from massive heights to go on an orbiting safari. After all the rigid tension of handling BUD limb by limb, the hang glider makes him a perfect vehicle, rushing you with a sudden liberation as you course through the sky, unhindered. But no, no, no. This isn’t what Grow Up excels at! It’s a game about overcoming the pull of gravity, about forcing a body beyond its limits, about pushing when everything else is pulling. Giving BUD the ability to fly (as becomes the case) is equivalent to Wile E. Coyote catching The Road Runner—it misses the point, the gag forced to expire before its time.

Once you’ve acquired the hang glider it’s hard to go back, to force yourself into the grind. But there will be a point when you miss it. As you hurtle through the air, realizing that the challenges that faced you at the bottom of the world—when you were eager to take them on—have disappeared. The hang glider might as well be a helicopter that picks you up and places you at the summit—in this case, the moon. As with the initial, tireless comedy of BUD’s imperfections, those moments of immense inspiration slip away with these new inventions. As a mountaineer with no peak left to climb, you turn your head away from the architecture of the skies, and look instead to return home.

For more about Kill Screen’s ratings system and review policy, click here.