Californium brings Philip K. Dick’s vision of the world to life

“Life in Anaheim, California, was a commercial for itself, endlessly replayed. Nothing changed; it just spread out farther and farther in the form of neon ooze. What there was always more of had been congealed into permanence long ago, as if the automatic factory that cranked out these objects had jammed in the on position.”

—Philip K. Dick, A Scanner Darkly, 1977.

///

Dimensions merge in Californium like pools of spilled ink on paper. Each one is given a predominant color so that they easily contrast—it makes the strange effect lucid if not any easier to get your head around. A cold, austere blue world leaks through in small spheres, its bathroom sinks and rigid cabinets consuming 3D pockets of the tangerine-orange version of 1967 California that Elvin Green inhabits. He may have a “brain corroded by mind-bending drugs and dime-store alcohol” but it doesn’t explain the intra-dimensional phenomena before him. Does it?

Upon playing an early version of Californium, it’s clear to see for any acolyte of the man, that it takes its ideas from (and is also a tribute to) noted sci-fi author Philip K. Dick. His oeuvre of fiction is the obvious source but the more prominent one is his spiraling thoughts post-1974. It was at this point that Dick was feeling the combined effects of schizophrenia and long-term recreational drug use. He had visions that revealed to him a supposed truth hidden from us all: there are multiple realities. Dick even went so far as believing that he could pick up signals from these other realities as they were beamed across the planet. Those who have read it will know that this is what protagonist Horselover Fat in Dick’s 1981 novel VALIS experiences.

Dick’s final years leading to his death resemble a fraying computer

We know that VALIS is a semi-autobiographical fiction as it mirrors the thoughts and confessions that Dick wrote down in his sprawling collection of notes. These were published as The Exegesis of Philip K. Dick in 2011. “That I am in direct mind-to-mind touch with extraterrestrial intelligence systems has been obvious to me for some time,” Dick wrote, “but what this means is not in any way obvious.” A year after VALIS was published, Dick had a stroke, his brain ceasing any and all activity, before the machines keeping him alive were switched off. Dick’s final years leading to his death resemble a fraying computer; color and images tearing across the screen before the final thrash of data dissolves completely. He was at his creative best when paranoid, delirious from drugs yet highly aware of the world, reaching inanely into inhuman curiosities. More and more he came to resemble the characters he had written: Bob Arctor in A Scanner Darkly, Rick Deckard in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, Joe Chip in Ubik.

Elvin Green in Californium is the archetypal Philip K. Dick protagonist. That is to say, he’s another version of the author himself, projected into yet another imagined reality. Typically, Green’s life has gone to the shitter. Daughter gone. Wife departed. A writer with writer’s block and an apartment cluttered with pills and papers; there is nothing of worth left in this man. This is when the television speaks to him. “I guess it’s the end of the road for you, Mr. Green,” it says through the static. No shit.

This talking, surveying machine (a common element in many of Dick’s novels) begins Green’s multi-dimensional journey either into a newfound clarity or a determined madness. You are tasked with hunting down more of these televisions, strewn as they are across the game’s small slice of Orange County; found in apartments, behind restaurant counters, one of them sits in a dumpster. Their location in back alleys and among the garbage is significant. It’s canon to Dick’s unstable fictions. Not only did he write of a perceived visual language seen in the formations of windswept trash in his 1976 novel Radio Free Albemuth, but in his personal notes, he also scrawled: “I do seem attracted to trash, as if the clue—the clue—lies there. I’m always ferreting out elliptical points, odd angles.”

Further, upon discovery, each of these televisions display a number—as a Roman numeral, perhaps in reference to Dick’s delusion that his second personality was a Christian in hiding from “hateful Rome”—that tells you how many symbols are in hiding in the local area. Many of these somewhat tedious-to-find symbols are among detritus, either of the streets or of rotting apartments, in toilet blocks, or behind fidgeting furniture and street signs, glitchy and corrupted by the scientific disturbance. You seek out these symbols to unlock the spheres of that penetrating alter-reality, letting its cerulean theme absorb pockets of Green’s reality. This becomes a repeated activity, at least in the game’s first chapter (and world), that leads to the method by which Green is able to travel to a new dimension.

But that second reality (of a total of four, it seems) is only glanced at in this preview—a towering blue metropolis in which Abe Lincoln is worshiped as a despot—and so our focus has to be on that starting location: the shiny orange-yellow version of California. The place is a reflection of where Dick himself spent the last years of his life, Orange County itself, estranged and cynical. It’s stylized to his vision of California as a commercial wasteland of repeated images and lookalikes. In a 1994 BBC documentary on Dick, fellow sci-fi author Kim Stanley Robinson describes Dick’s vision: “Everything that I see is plastic and glass and gaudy colours, and strangely made. Human beings begin to take on an odd look. Our clothes are the same sort of plastic oddness, and therefore our eyeballs begin to take on kind of a glassy look. The entire world begins to take on a kind of a fake, artificial ‘made’ quality.”

It gives them that immediate plastic look

All of this can be seen vividly in Californium. The painted colors of its high-rises are so bright and ubiquitous as to be almost unbearably fake-looking. There’s an indisputable commercial glow about the place that is struggling to keep its shape. The slanted fonts of shop signs flicker in their neon disguise. The same model of luxurious car cruises the asphalt to resemble a production line. Rooftop palm trees and billboards hold up the skyline. This street hides the same artifice that the sunglasses in John Carpenter’s 1988 movie They Live reveal. There’s also something to be said of Californium artist Olivier Bonhomme’s work in comparison to that of celebrated French cartoonist Jean Giraud. For the sci-fi detective novel The Long Tomorrow, Giraud created an illustrated interpretation of its urban sprawl: a tall labyrinth of mercantile architecture, criss-crossed with the tangle of downtown traffic at every level, all of it washed in bright yellow. Whether Bonhomme meant to recall Giraud’s work with his own sun-kissed city isn’t certain, but it’d be an appropriate gesture to make, as it was that particular cartoon metropolis of Giraud’s that would go on to inspire Ridley Scott for the designs of Blade Runner (of course being the film adaptation of Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?).

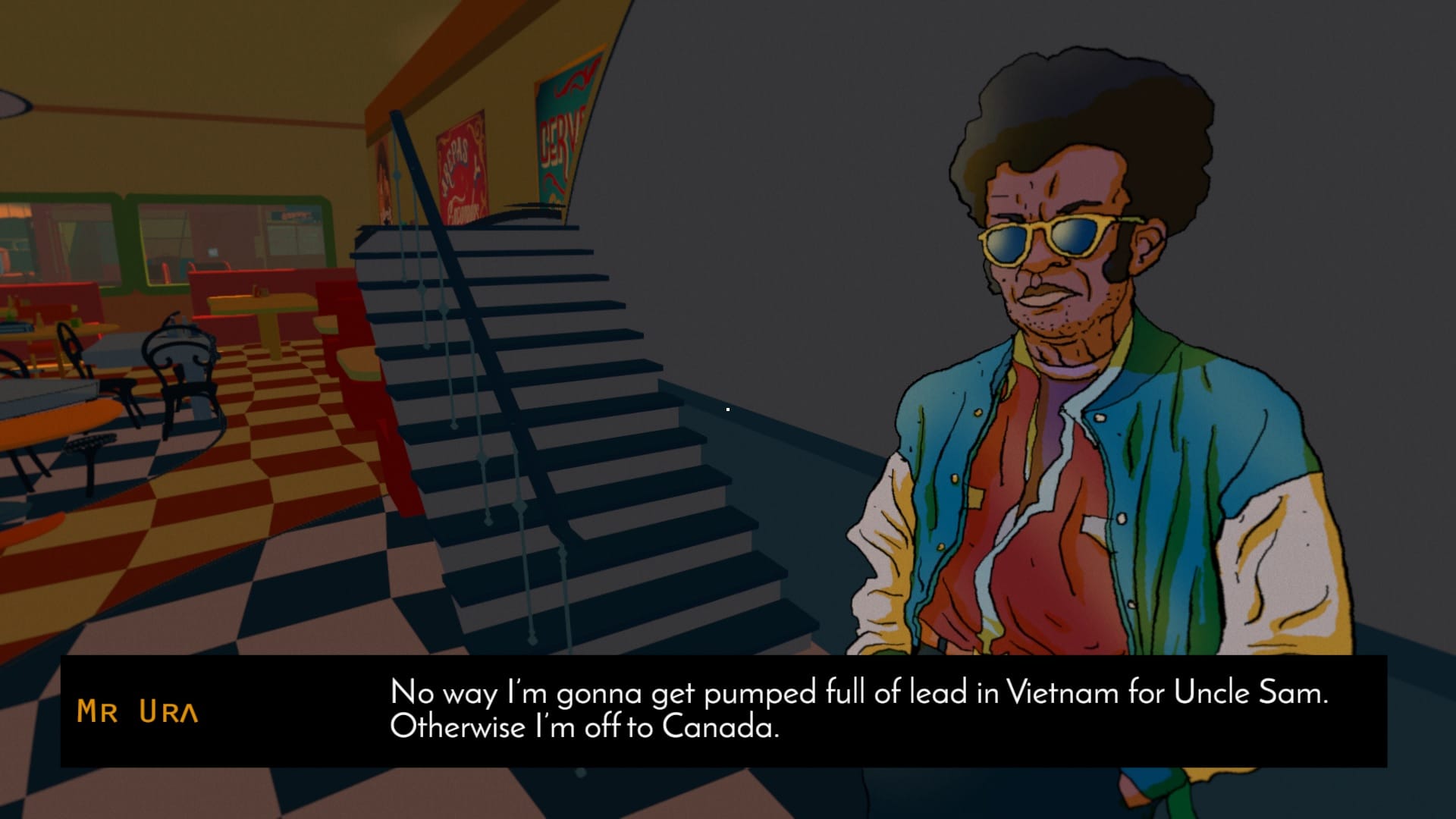

Beyond the inanimate are the people in Californium to consider, though, perhaps there isn’t much difference between the two. In conversation, the residents you meet seem fine if a little displeased with Green; the government agent, the editor, the landlady, the policeman. But they look anything apart from fine. In this 3D world, they are realized as obtrusive 2D sprites, the kind that pivots to face you from whatever angle you stand from them, unable to forgo their perpetually frozen expressions. Flat shadows and cut-out features. It gives them that immediate plastic look that Robinson described. (Perhaps they are androids…) While this sprite technique is nothing new to videogames, when you’re looking through Dick’s eyes, it takes on new meaning—an effective tool in realizing Dick’s world as he saw it.

As dense as it already is with glossy simulacra, it seems that Californium will only spread out from this starting point, across the length of Dick’s work. We will see through the glassy eyes of the man in his penultimate years, light and shape steered towards our brain as they were to his, California a rich text for the theater of meshugaas. Except it doesn’t throw away the author’s theories as delightful madness, instead giving them another chance as plausible fiction, for us to realize what Dick had come to terms with when he famously said, “It is sometimes an appropriate response to reality to go insane.”

You can find out more about Californium on its website. It should be out for PC later in 2016. It’s being made possible by ARTE, Darjeeling, and Nova Production.