Can the beautiful, beleaguered isometric perspective make a comeback?

Back in the late 80s and early 90s, before dedicated graphics cards and our modern processors, there was always a question of power. Games needed it and computers couldn’t provide it. In order to model something in 3D you needed a fair amount of this juice. Nowadays, most computers come with that and more, but what did developers do if they wanted to do 3D before that power was readily available? Well, they sort of faked it: They used isometric projection.

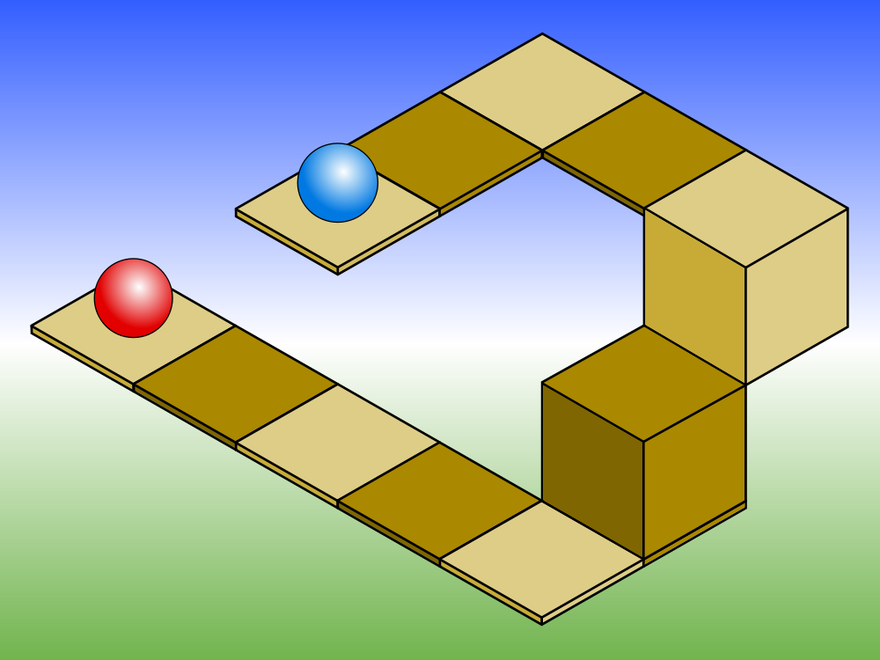

One of the arts of making videogames is finding creative solutions to difficult problems. If you can’t make something actually 3D how can you represent it in 2D so that it feels 3D? Isometric projection does exactly that. It tricks the human eye into reading depth when in fact there really isn’t any. The three quarter view angles, the shading, and the construction of the physical objects all work together to create a rather elaborate illusion.

Isometric projection is something that is fairly ubiquitous now, found in everything from Farmville to Diablo. But just because isometric was born of needier times does not mean that it’s seen its last days. Chris England of Goldhawk Interactive is currently working on a game born, bred, and steep in isometric: that is, the forthcoming Xenonauts.

Xenonauts (he pronounces it in the Queen’s English, as zen-oh-nots) is a faithful adaptation of a game that is very near and dear to my heart: X-COM. That’s right, the one with the hyphen, the hardcore 1994 PC version of the game that was remade, with much aplomb and grace, as 1994’s XCOM. England’s game promises to be more than an adaptation, as Firaxis’s 2012 version was. Xenonauts aims to be a hyper-real successor to the look and feel of the original by going with an art and architectural style that improves on the original without completely changing it, an art and architecture that is deeply entwined with isometric projection.

Over the last few years England and his team have been painstakingly building a game that straddles two very different design paradigms. Xenonauts must be true to the 1994 X-COM but it must also make the justifiable improvements on a game that is 20 years old now. Building that particular world has proven difficult, something that has given England new perspective on isometric and the challenges presented by building a 3D game in a 2D engine.

Doing so requires several “contrivances” as he calls them; making a game like Xenonauts requires workarounds in order to make its workarounds work. Which is to say that using isometric projection to make a 3D world in a 2D world creates its own set of problems. Unlike fully three-dimensional games, England tells me one of their biggest challenges has been their inability to use ray tracing, the technical term for determining the path a bullet takes. England used Valkyria Chronicles as an example. In Valkryia, a unit can fire at another unit and the game will then model how that bullet moves through the gamespace and either strikes the target or doesn’t. In Xenonauts, that simply isn’t possible. Instead of being able to trace bullets using physics and vectors, isometric tiles force England to use math in order to determine whether a bullet hits an alien or not. At first glance that might seem really odd, but it’s essentially what tabletop games have been doing for years with dice rolls. However, when Xenonauts does it, it takes in a much higher order of variables and does the calculation without the need for a die.

Isometric tiles force Xenonauts to use math to determine whether a bullet hits an alien or not.

Something that a layman might consider as simple as a tree presents multiple problems in isometric tiles. In the original X-COM, in-game objects had layers of varying size which constituted “obstruction” in order to account for the fact that trees were not uniform in shape but still needed to fill an entire space. A soldier shooting at an alien past a tree wouldn’t shoot up at the widest part but the tree still needed to have a widest part. Firaxis sort of fudged the design so things either had a high or low chance of blocking. While aesthetically pleasing, this leads to many of the bullet clipping issues and objects of dubious proportions. In order to streamline this process, England’s team has instead imbued objects with the “obstruction chance.” No method is perfect but neither is isometric, and that’s kind of the point.

However, these contrivances can only carry you so far. England told me that there is a fairly simple reason that his game does not have a rotatable camera: it’s more work. In order to rotate the camera every object in the game must be painted from every possible angle, something that’s hard enough without taking into account the beautiful hand-painted realistic aesthetic Xenonauts is going for. Isometric also has a built-in flaw in the way that it tricks the eye: it’s sometimes technically impossible for the human eye to discern when an object is on a different elevation than another object without visual clues.

Making a game with aliens also is fairly difficult in a tile-based isometric game for another simple reason. Aliens like to pilot things like flying saucers, which are round, and round things are hard to do when they must fit in a little square or “tile”. Each of the little rounded edges of the ship must fill an entire tile so without some ninja artwork and programming skills it presents a challenge where players will see a space that seems as though it could be occupied but is actually filled with a sliver of spaceship.

But for its difficulties England and I agreed that there are a few key advantages of a tile-based, fixed camera, isometric set-up, like in Xenonauts. The perspective allows the developer a massive amount of control over their environment and, in particular, how that environment looks. Being able to control the perspective enables the developer to ensure that the perspective in question is beautiful, something easily seen in a game like Bastion. However, the tiles also allow England and his team a level of randomization that hand-drawn isometric games cannot have. Xenonauts has over 30,000 different hand painted tiles, the vast majority of which are ground tiles, which come together in different ways to create unique settings. England explained to me that it takes thousands of unique tiles in order to make a field of grass or a backyard look believable. Though the game is never truly random (the levels themselves are each handcrafted, another feat) there are elements of randomization which are only possible with such a vast library. Though a map may always contain the same buildings their contents might be wildly different.

It’s a fair argument that tile based isometric games may soon be heading the way of the point-and-click adventure, a sort of “legacy genre” that only a select few developers keep using. England himself admits that the reality of isometric tile-based games is that they do not mesh well with modern aesthetic sensibilities and desires. People really liked the new aesthetic of Firaxis’s XCOM, but those who didn’t will soon have Goldhawk’s Xenonauts. Though I doubt iso will see the modern renaissance that rougelikes are getting, here’s to hoping that someone will carry the torch ever on, and maybe, someday, find a way to get curved objects to fit nicely in square tiles.