Towards the end of the first season of Telltale’s The Walking Dead, the player is asked to smear the decaying remains of a corpse over a small child. At the tail-end of a narrative that has already seen the girl, Clementine, separated from her home and her parents, it acts as something of a thematic coup de grace, parting her, at long last, from the innocence that hangs fraught over her shoulders for so long.

It is, at once, a step forward and backwards for videogaming, representative of a move towards more diverse characters and situations, but also, in their ruination, an unease therein.

There’s a long-standing assumption that videogames are childish. Perhaps owing to their humble beginnings in the domain of gadgets and toys, not to mention their relatively new status in the grander scheme of artistic media (we still talk about the medium as “in its infancy”), videogames have consistently struggled with the question of maturity. Clementine’s continuing story is just the latest means by which it has been asked.

Are videogames childish? It’s a hard question to answer, although one thing’s for sure: if they are, they’re doing a poor job of representing their own.

Child characters like Clementine are a rarity in videogames; rarer still ones that have defining characteristics beyond their youth. As an abstract idea, children are a blank slate, largely untainted by the politics of the past or the fears of the future, and are consistently exploited in this capacity, used as canvases on which to paint a larger ideology. In many videogames, they exist solely to be killed or saved, as symbols or props in larger, adult-centric narratives.

In both literature and cinema, youth as a concept is often used as shorthand for a wider reflection on society or the self. 1976’s Carrie is a classic example of this approach; the titular antagonist’s prom-night blood shower—and ensuing rampage—a clear remark on the abusive world in which she was raised, and which we are also implied to inhabit. Similarly, a whole industry of fiction is predicated on the idea of the downtrodden child, both as a point of voyeuristic interest and inspiration.

In videogames, however, this seems to be the dominant way in which children are represented. At the very least, Carrie was granted the lead role in her film, not to mention some degree of agency over her narrative, and there are vast swathes of films and books: Harry Potter, Little Miss Sunshine, Boyhood, and The Goonies, to name just a few, that treat children and adolescents as something more than their age. These works connect with the touchstones of youth—like innocence, purity, or discovery—without making them a defining feature of their younger characters.

Videogames are slightly more limited in this respect. When it comes to representing children as people, they trip over themselves time and time again. In videogames, children are consistently silenced or ruined, seemingly because they have no better roles to play.

For characters like Clementine, the days of the innocent bildungsroman are gone, lessons learned replaced with things lost, to the point at which any given coming-of-age is shown to have an explicit price; a turning point when childhood is rendered irretrievable. In The Walking Dead, with no other option, the player is forced to participate in Clementine’s own coming-of-age, a single prompt on the screen encouraging them to initiate their own prom-night blood shower over the young girl’s innocence.

It’s the final indication that she is, for narrative purposes, a dummy; a facsimile of a person, better representative of the people around her rather than a personality in her own right. She is a cipher for the player’s lasting effect on the world, the game’s persistent reminders that “Clementine will remember” your actions clearly situating her as an object to be acted upon, rather than one acting in her own right.

For better or worse, Clementine is one of the medium’s better examples. Many videogames don’t even afford their child characters dialogue. 2011’s Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3, for example, is far more brazen in its messaging: in an interlude titled “Davis Family Vacation,” the player is made witness to a chemical attack on London, in which a young girl is explicitly highlighted as the first casualty. Her death ultimately suggests two things: that the bad guys are, in fact, bad, and that chemical weapons are bad, too. The inclusion of the child says nothing, at its worst appearing as a crass gimmick for a series increasingly running out of ways to shock its player through sheer spectacle. This approach is unfortunately all-too common across videogaming.

There’s no question as to why children are consistently used in this way. The idea of childhood is powerful. It’s something that advertising companies and campaign trails have acknowledged for the longest time: children are a valuable cultural currency. The turn-of-the-century ideal of childhood—of purity and innocence—is a potent symbol, one promoted daily on billboards, in papers, and in our collective psyche.

That videogames would want to remove this innocence isn’t surprising. On paper, it’s deceptively readable shorthand. What better way to strike at an ideal than through the death or ruination of its biggest proponent?

In practice, however, it’s indicative of a larger problem with videogame narrative. It would be a staid moral argument to suggest that videogaming’s current use of child characters is wrong, especially when so many cases are contingent on the artistic context of a work. Rather, the issue is one of representation. The experiences unique to childhood are being ignored in favour of heavy-handed moralising and woefully exploitative attempts at engendering sympathy. In adult-oriented videogames, children are being granted no meaningful roles other than as narrative objects, and it’s narrowing the scope of stories told.

The first BioShock game is a particularly notable culprit in this respect. While it may have been “a curiosity for a mainstream press that often writes videogames off as childish or thoughtless pursuits,” it’s often easy to forget that BioShock framed its narrative around a particularly simplistic depiction of its younger characters.

As the player traverses BioShock, she is given the option to either save or kill “Little Sisters”: a collection of genetically-altered children who, in spite of an apparent evil, can be redeemed at a button’s press. At the game’s conclusion, the player can achieve one of two endings, both of which are contingent on how she treated the Little Sisters she encountered. If the children have been saved, the player dies happy, and surrounded by friends; if the children have been killed, the player is seen single-handedly helming a war-machine and enacting unspeakable violence on the world around them.

Needless to say, it’s an extreme split, and one that was met with an appropriate degree of criticism. For all of the game’s loftier flirtations with ideas of selfhood and choice, BioShock’s core argument is grounded within the relatively trite framework of children as a symbol of good; without any explicit consideration paid to how these children interact with the system in which they are situated. The grand finish of BioShock’s narrative is based around the moral non-quandary as to whether to save or kill children, and suffers for its simplicity.

It’s this idea of simplicity that hinders videogaming’s attempts at children characters. In reducing children to a few simple ideas, videogames have only surfaced an unwillingness to engage with non-violent, human issues; instead including them as sideshows within larger, conflict-driven narratives. As a result, children characters have a tendency to feel out of place, or at worst, unwelcome, as was the case with BioShock’s endings.

This becomes particularly prominent in horror genres. Ever since Henry James’ The Turning of the Screw first brought the disaffected, ghostly child to the mass-market, horror fiction has become increasingly tied with ideas of youth. Horror classic The Exorcist traces a concern with a growing generation of secular teens, all of whom—in their own symbolic way—were at risk of succumbing to sin without the moral strictures of old to guide them through life. Similarly, the oft-imitated children of Japanese horror films like Ringu and Ju-On paint a distinct strand of guilt amongst the boomer generation, in which the consequences of their own lifestyles come back to haunt them in the form of the ghostly, impoverished child.

By this point, the bite has largely been lost. The child as a horror trope has been exploited time and time again, to the point at which discordant nursery rhymes and diminutive apparitions are more likely to instill a sense of embarrassment than dread.

That hasn’t stopped it from proliferating, however. Within videogames, the “horror” child is seen in abundance. From F.E.A.R.’s Alma to Dead Space’s day-care monstrosities, disfigured and discontented children run rampant, often with direct reference to their cinematic counterparts. There’s often little narrative rhyme or reason to the child’s inclusion;, in many cases, it’s merely trading on another creator’s years-old concerns.

There’s a tendency to accept the child’s presupposed status a symbol, rather than engaging with it in any new or meaningful way. Just consider the number of videogames that utilise children’s chants as a horror motif, the recent surge of games like Amy and The Last of Us that have modelled themselves on the post-apocalyptic parent-child dynamic of Cormac McCarthy’s The Road, or even the prevalence of visual tropes like the Empathy Doll Shot.

Videogames have become overly reliant on linear methods of storytelling when it comes to children characters. Due to obvious ethical concerns, children have to be constrained to areas or scenarios where violent interaction is made significantly less likely, yet the extent to which videogames tend towards conflict means these areas are few and far between. Either they are set along a number of prescribed paths, like in The Walking Dead, or they are simply held away from the action, as in something like Fallout 3 or any given open- world sandbox,; their tales dictated solely through text or cut scenes.

The social context of childhood has forced them out of the stage of play, something which—when combined with videogaming’s tendencies towards violence not only as an aesthetic, but as a means of interaction—severely limits children’s capacity to interact back with the player in any meaningful way. As long as this is the case, children will remain imitative, simple, and out-of-place, if present at all.

There is a great potential in videogames to address the question of what it means to be young head-on, rather than as a supplement to a narrative that already has its thematic concerns set in place. Similarly, there’s a space out there for young characters that don’t serve some greater purpose; that can provide more diverse voices to videogames: voices that don’t belong to adult white males in tank-tops and tac-vests. Yet it’s reliant on our ability to put down the gun and confront children on their own terms.

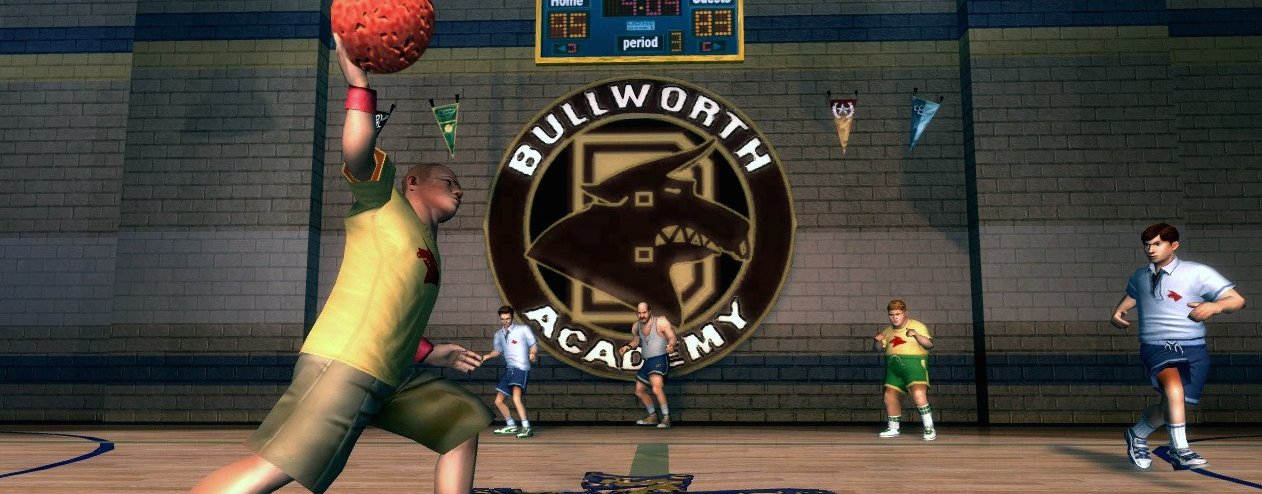

A few breakthrough games have got it right. Rockstar’s Bully, in adapting life in a boarding school into a sandbox videogame, did a great job of representing the trials and tribulations of youth on their own terms. Similarly, The Walking Dead’s second season is giving Clementine a story of her own, while Ubisoft’s recent Child of Light opts not to suppress and violate its child’s imagination and hopes, but rather twist them into an aesthetic of their own. Clearly, children aren’t unwelcome—merely underrepresented.

In his acclaimed documentary A Story of Children and Film, Mark Cousins traces an image of the child in cinema that is fundamentally unique to children. In a “realist portrait of real children” Cousins identifies a nostalgic, alien potential in child characters: one wholly absent from their adult counterparts. Children’s stories, the documentary posits, glimmer because there’s universality to them. You would think that this universality would bleed through into videogames.

For now, it hasn’t, and this, funnily enough, is the most demonstrably childish thing about modern videogaming. By silencing diverse voices in favour of violent assertions of maturity, videogaming has found itself in such a child-like rush to grow up, to get as hyper-violent and cosmically meaningful as possible, that it has neglected to look back, at the expense of stories like those of children—stories that still want, and perhaps need, to be told.