When Microsoft’s Kinect launched in 2010, heralded by the crash of broken sales records, it must have seemed like a new dawn, the emergence of a fresh, revitalised form of gaming made achievable by the advance of technology. Yet by the time the Xbox One was announced with Kinect at its core, consumer interest had waned. While support for Kinect’s functionality was widespread, it was difficult to claim that its technological potential had been matched by equally revolutionary software: beyond Dance Central and its imitators, few titles could be argued to be more than traditional games with optional—and often temperamental—motion controls tacked on.

It’s a cautionary tale which the new wave of virtual reality would do well to heed: since the launch of the original Oculus Rift development kits, the first wave of big-name titles announced to support the Rift—from EVE: Valkyrie to Hawken to Elite: Dangerous, from Doom 3 to mods for Team Fortress and Half-Life—are predominantly first-person shooters and cockpit-centred flight simulators, common archetypes enhanced by the all-encompassing involvement promised by VR.

These experiences are well-positioned to be a vital touchstone at VR’s rebirth, something familiar for players—and developers—to grasp on to while exploring this new medium, one which initially seems very familiar yet brings its own nuances to interactive entertainment. Yet these are also designs heavily inspired by traditional gaming, fast action games for a medium which may not be especially well-suited to fast action. If VR as a fully-immersive medium is to achieve its potential, what key strengths can it offer? In what aspects might it potentially surpass gaming as we know it?

VR’s most potent strength is in placing the user into an environment, portraying a convincing sense of place, and mapping the most primal human interaction—looking around—to the muscles used for that motion in daily life. In a similar fashion, traditional videogames are often associated with a voluntary loss of self-awareness, the player’s direct control over their avatar enabling them to identify with the character at a very instinctual level. This sense of being a character—of claiming direct ownership of their actions and successes—is a major contributor to the pleasurable escapism of gaming, and the enhanced sense of place and exclusion of external stimuli granted by a VR headset intensifies this effect. It’s this identification which may hold the greatest potential for VR as a distinct medium from traditional videogames. So what might a gaming experience conceived with this in mind be like?

Remy Karns, lead designer and writer of Classroom Aquatic, might have an idea: “A lot of people, when they finally get their hands on a Rift, think: ‘Okay, now I’m going to translate a proven concept onto it’,” says Karns. “We looked at the Rift and said ‘This is what we’re going to be designing around; let’s create ideas of what the Rift can do’, and that opened up a lot of new possibilities.”

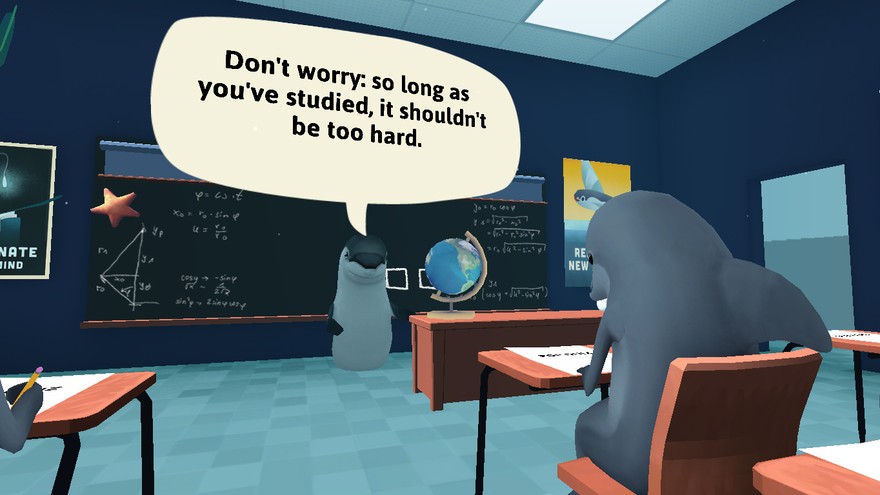

Originally conceived by developer Sunken Places as part of Oculus VR’s 2013 game jam, Classroom Aquatic casts you as the lone human exchange student at a school for hyper-intelligent dolphins. When faced with a pop quiz on such eclectic topics as Neoplasticism, Proust and ancient Egyptian statuary, cheating is your only recourse, but you’ll have to evade, distract and manipulate your teacher and classmates to get away with it.

As pitches go it’s intriguing, a collision of absurdities likely to generate a smile on all but the most stoic of faces. Yet beneath the surrealism it’s remarkably easy to slip inside your avatar’s head and accept the illusion as reality, evoking the uncertainty of facing an impossible test with discomforting familiarity. Classroom Aquatic seeks to offer an emotional experience, merely informed by the mechanics of the stealth genre; the exchange student in the diving suit is an empty cipher, a space for you to fill with your own presence, your own emotions and memories. Your surroundings call back to an archetypal school environment, neatly-arrayed desks in front of a towering blackboard, jangling anatomical skeletons and walls lined with maps and trivia. With so many familiar elements in place, it’s easy to rationalize the fish swimming outside the window and the dolphins glancing suspiciously at you, covering their test papers with their flippers.

Their distrust is not without good reason. It’s critical to the experience, Karns explains, that the questions seem fair and that it’s not inconceivable that someone might know the answers, but the careful balance between highly specific knowledge and widely disparate topics conspires to force you to rely on underhanded tactics. “It’s strange that everyone seems to realize what they need to do in order to cheat,” he says.

We’ve all been in situations where cheating is a choice—one with considerable associated risk—and where both failure and being caught are equally unthinkable. The patrolling teacher, the classmates jealously guarding their answers, the carefully lined-up erasers on your desk all evoking memories of when test results meant everything, recalling the queasiness in your stomach when you last opened a test and realized you knew none of the answers. “It’s always fun seeing people play the game employing real-world cheating strategies. You know, the slow lean over just to get an edge out of the side of their eyes peek, or waiting for people to switch the page.”

It has been suggested that a major aspect of the appeal of fiction is that in the process of identifying with a character, of empathising with their predicaments and emotional states, you can experience situations which would be undesirable or have negative repercussions in reality, but are interesting to explore emotionally or cognitively in a controlled manner. While this is true of other media, from literature and movies to traditional videogames, the reduced cognitive distance between you and your avatar in VR could make it easier to achieve the desired heightened emotional state.

For Karns, “othering” the player is a crucial part of Classroom Aquatic‘s atmosphere, of making you feel unprepared for the test to come. “You’re the new kid … the fish-out-of-water. Everyone else is a dolphin, and you’re different.” Worse, everyone else makes it look easy, while you’re stuck staring at a paper covered in impossible questions. Even without a headset, Sunken Places’ proof-of-concept demo portrays a convincing illusion, but within VR it becomes a surreal pseudo-nightmare, your cetacean teacher screeching instructions and accusations at you in a language you don’t understand as you desperately try to cobble together answers from the snatched glimpses of your classmates’ papers.

The tipping point, where a VR situation deteriorates from enjoyably intense to distinctly unpleasant, is something that game developers will have to figure out as they go along. The emergence of a new medium means reassessing many of the established rules about what can and can’t be done, and it’s an unfortunate truth of VR that many elements of traditional game design which work reliably at a distance are a source of considerable discomfort when only inches from your eyes. Oculus VR’s extensive best practices recommend a comfortable walking speed of 1.4 m/s to minimize motion sickness—less than a third of the standard movement rate in Minecraft, for example—and commonly used conveniences such as temporarily suspending player control for cutscenes are strongly discouraged.

These are familiar considerations to Karns. “It feels kinda weird to walk around when you’re sitting down in your living room,” he explains. “When films came out, we treated it like theatre—it took us a while to figure out we can cut scenes and have different angles and stuff like that—and when we took certain games and translated them to different play styles, we had to change those too.” In the same way that videogame design philosophies have developed over the past thirty years to create the highly polished experiences we’re accustomed to, so VR will grow through experimentation and iteration, and in turn inform other media. “Just as videogames made us better novel-writers and filmmakers, the Rift will make us better at making games.”

Hopefully, as developers become more comfortable with the constraints and strengths of VR they’ll reach further, creating more nuanced emotional experiences to identify with and allowing players to explore a wider variety of situations, both positive and negative. Karns espouses VR’s potential to escape the traditional goal structure of first-person gaming, where your primary impetus is the avoidance of bodily harm. “We wanted to give you a motivation that was not violent, not physically confrontational, and it created this new place where you can go. “Instead of dodging gunfire and hoping you don’t have to respawn two minutes away, you’re trying to avoid social ostracism. Somehow that’s a scarier prospect than a bullet to the head.

“It’s something that’s very close to home,” says Karns. “I imagine the majority of people who play shooters have never been in a situation where someone is firing a gun at them, so we can only take the game’s—or the media’s—portrayal of that as the cause for fear, whereas we have been in situations where we’re cheating on tests, and it’s completely nerve-wracking.”

If the Oculus Rift and Sony’s Project Morpheus are successful enough to evolve beyond expensive novelties, VR has the potential to offer a new form of entertainment, one more suited to exploration and introspection, and perhaps simulated cheating is only the beginning. In the process, perhaps some childhood psychoses can finally be put to rest: “It’s the healing element of games. When you’re in a nightmare, you’re never faster than the monster, and you can never say ‘You know what, I can beat this test even if I didn’t study for it. And once I put my teeth back in and remember to put on pants, I’ll just do that!'”