Dad? Where’s Mom? I can’t find her in this videogame.

I’ve always taken my mother for granted. She bathed me when I couldn’t walk or talk; she gave me ginger ale when I was sick; she bought me every single Sailor Moon movie on VHS. I would thank her in words, but I don’t think I ever really thanked her in the truest sense. Needless to say, I had a good mom. Not everyone’s so lucky.

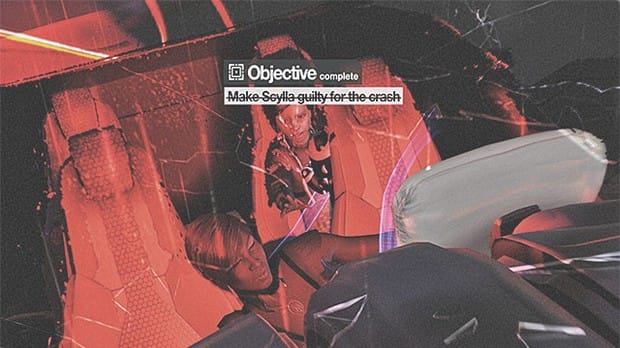

In Remember Me, the protagonist Nilin is tasked with hacking the memories of her own mother, a diabolical CEO with the equally sinister name Scylla Cartier-Wells. It’s not without warrant–memories are getting commodified, used and abused, and she’s running the show.

Nilin is tasked with hacking the memories of her own mother

It’s not without precedent either. Mothers in games are so often adversarial, abused or… well, deceased. You need not look far for a laundry list of ill-fated mothers: Allie in Ni No Kuni dies, Callisto in God of War dies, The Boss in Metal Gear Solid dies. They don’t always die, of course; sometimes they are just plain missing because they expired even before the story begins: The Last of Us, BioShock, and Final Fantasy X. The playable mother character is certainly rare.

The playable mother character is certainly rare

The marginalized mother of games today is a very narrow expression of parenting. Mothers have been exploring their relationship to parenting and to their children through art for ages—so why is it uncommon in games?

Brenda Romero is a mother and a game designer. She is the game designer in residence at U.C. Santa Cruz and co-founder of Loot Drop, an independent game company. She has received much acclaim recently for her game Train, a serious board game about a sensitive historical topic—don’t let anyone spoil the ending before you play it though, because the experience is seriously powerful.

Like most parents, not a week passes without perpetual amazement and delight in her children. But it’s more than a mothers pride at work. “Watching them informs our ideas of how and what we are designing, wishing we could find the game that could teach them x or y. They’re ridiculously influential,” she said.

“Watching them informs our ideas of how and what we are designing”

Romero’s daughter Maezza came home from school one day and told Romero what she had learned about the Middle Passage. When Maezza was done, Romero could tell that she hadn’t grasped the gravity of it; she needed to help her daughter understand the real tragedy of the Middle Passage. From that came Romero’s The New World, an analog game where the player tries to get families from one shore to the other on a limited food supply. Romero made and played this game with Maezza after school that day; needless to say, they rolled the dice and the tragedy took shape.

Now part of her The Mechanic is the Message collection, The New World was more than just a conversation between a mother and daughter about a dark moment in world history. Romero wanted her daughter to understand the Middle Passage beyond the text on the page. “As a game designer, games help me teach them some difficult things.” For those of us without kids, parenting may look like it’s all about babies, diapers and college loan co-signing. At its core, however, parenting is a lifetime of teaching, learning and interaction—three inherent aspects of game design.

“As a game designer, games help me teach them some difficult things”

Parenting, of course, is often a two-way street—Mom and Dad probably learned a lot from you too. But the power that children can bring to a mother’s creative process has been proven time and time again in every medium imaginable. Brenda Chapman, co-director on Pixar’s recent film Brave, quipped that the main character Merida was largely inspired by her relationship with her daughter. Tina Fey told Conan O’Brien that many of her best lines as Tracy Jordan on 30 Rock came straight from conversations with her daughter—“Touch my knees-butt.”

Perhaps no one better exemplifies the power of a bond between mother and child than Anne Waldman, a poet who wrote alongside the Beats. Waldman began her Iovis Trilogy soon after her son Ambrose was born. He opened her eyes to the patriarchal structures that boys and men are subject to, and she chose to explore those structures in her book. Watching him interact with the world as a child was enlightening and, in many ways, shaped her work.

She says in the Contemporary Authors Autobiography Series that, “My child became my teacher.” Her son’s influence in her work is evident even today in their duet performances, she reading her poetry while he accompanies on the piano.

Motherhood and fatherhood do overlap in many ways, so why does fatherhood so disproportionately take the spotlight in games? After all, the woman’s experience, as a mother is, in part, different from the father’s. The pregnant mother and child are interacting and forming a relationship before they’ve even held hands.

Unfortunately, game studios do not always go out of their way to accommodate pregnancy; Romero told me that at times during her career, “the companies I was at didn’t have maternity leave until I was expecting.” The conditions of production have a profound impact on the kinds of games produced. When production spaces fail to provide maternity leave, safe spaces for breast-feeding and childcare, then it may not surprise you that Romero said, “isn’t it sad that the industry doesn’t have a place for women to be both developers and mothers. Some feel they left something behind but couldn’t reconcile being both.”

Stony Brook researcher Laine Nooney has spent the last two years studying the work of King’s Quest game designer Roberta Williams. Williams, a mother, became a successful game developer while raising children and her work often incorporates family themes and characters. Nooney noted that Williams is known for designing her games around the kitchen table—a place where she could work and still be with her children.

A workplace encouraging allnighters and ridiculously long work hours might not jibe with everyone’s lifestyle

Nooney says that, “In contemporary game design, making games in the domestic space is seemingly out of the question because of the grinding ‘late-night’ labor, and so we are missing games from people whose lives can’t match to those expectations.” Not every mother would want to work from her kitchen, of course. However, it shows us that a workplace encouraging allnighters and ridiculously long work hours might not jibe with everyone’s lifestyle.

The normalization of these life-consuming production spaces marginalizes developers who need a different kind of space. Williams was lucky enough to have access to the tools that could afford her to make games in a space that she was comfortable, and so now we can play Kings’ Quest to our content. While mothers and their needs are minoritized in the production space of games, games addressing their experiences are less likely to be made, and playable mothers may continue to remain few and far between.

Those moms could teach game developers a thing or two about algorithms

There are some games that do engage with motherhood, however; Shelter, a game about a mother-badger protecting her young in the wild, for example, or The Sims, with lady Sims capable of becoming pregnant, taking maternity leave and giving birth. But these days, fathers and fatherhood narratives are all the rage: The Last of Us, Red Dead Redemption, Dishonored, Heavy Rain, Bioshock—I could go on. This is a welcome adjustment, but it’s only part of the picture.

A couple weeks ago, a short montage of people playing games with their moms aired on Jimmy Fallon, and, as usual, it’s a big joke. Really though, the joke is on videogames. Those moms could teach game developers a thing or two about algorithms—have you ever tried to decrypt kid-speech? It’s hard, and they’ve got it down to a science.