What’s unusual about Leo Castaneda’s current project is that he has inverted one of videogame development’s immemorial systems. An established procedure in development houses is to employ illustrators to produce concept art. This is then used to draw together a united vision: “this, people of the development team, is how we want this game to end up,” someone probably said once in a board meeting, presenting a gallery of inspiring landscapes and portraiture.

Castaneda, an artist that says he is “working in the intersection of painting and virtual reality” (and who has written about the parallels between art history and videogame graphics) hasn’t been producing a videogame based on concept art. What he’s been doing since 2009 is working on a series of paintings derived from videogame structures. That’s the inversion.

It started out as a solution to a problem that Castaneda says many face in the world of painting: “how to gain image freedom and work between abstraction and representation.” Castaneda wanted to paint whatever he wished and to play within limitations across a series of paintings and drawings. Yet, how to do that without it all becoming a mess of random ideas that wouldn’t engage an audience? The answer lay in the 1991 Sega Genesis platformer Sonic the Hedgehog.

“Level Two” and “Level Three,” 2009, Leo Castaneda

What Castaneda saw in Sonic, and other early sidescrolling videogames, were structures that allowed them to logically proceed from one random location to another. Taking Sonic as the example, we see the blue hedgehog travel from a fire temple, to an oil rig, and eventually to outer space. And at no point do these huge skips in the journey come across as lunacy. Castaneda attributes this to the structures that are in place to transition you from one location to the next. These structures in this case are “Levels” or “Stages;” simple labels that define the boundaries in what would otherwise be a confusing adventure from place-to-place. They provide a pattern you can understand: the first location is Level 1, the next location is Level 2, and so on.

In retrospect, this level-based labelling system in videogames is, as Castaneda described it, “arbitrary.” However, without these basic structures there, as Castaneda also reasoned, “the continuity of things would be too chaotic to understand.” These days we have cutscenes giving us a narrative transition between two areas in a videogame, or in open world games we may have our avatar run the distance to connect the two separate spaces. But in games such as Sonic the Hedgehog, it’s only in referring to each location as a “Level” that fills the gap between them. We don’t need to see Sonic travelling between each Level, nor do we question it, we simply accept the progression through each numbered Level. It’s in seeing the strength of this system to connect two random ideas or places, that Castaneda recognized these videogame structures as the glue he sought, and so he adopted them for his series of paintings. He translated the terminology directly, referring to his paintings as a “Level” or a “Boss.”

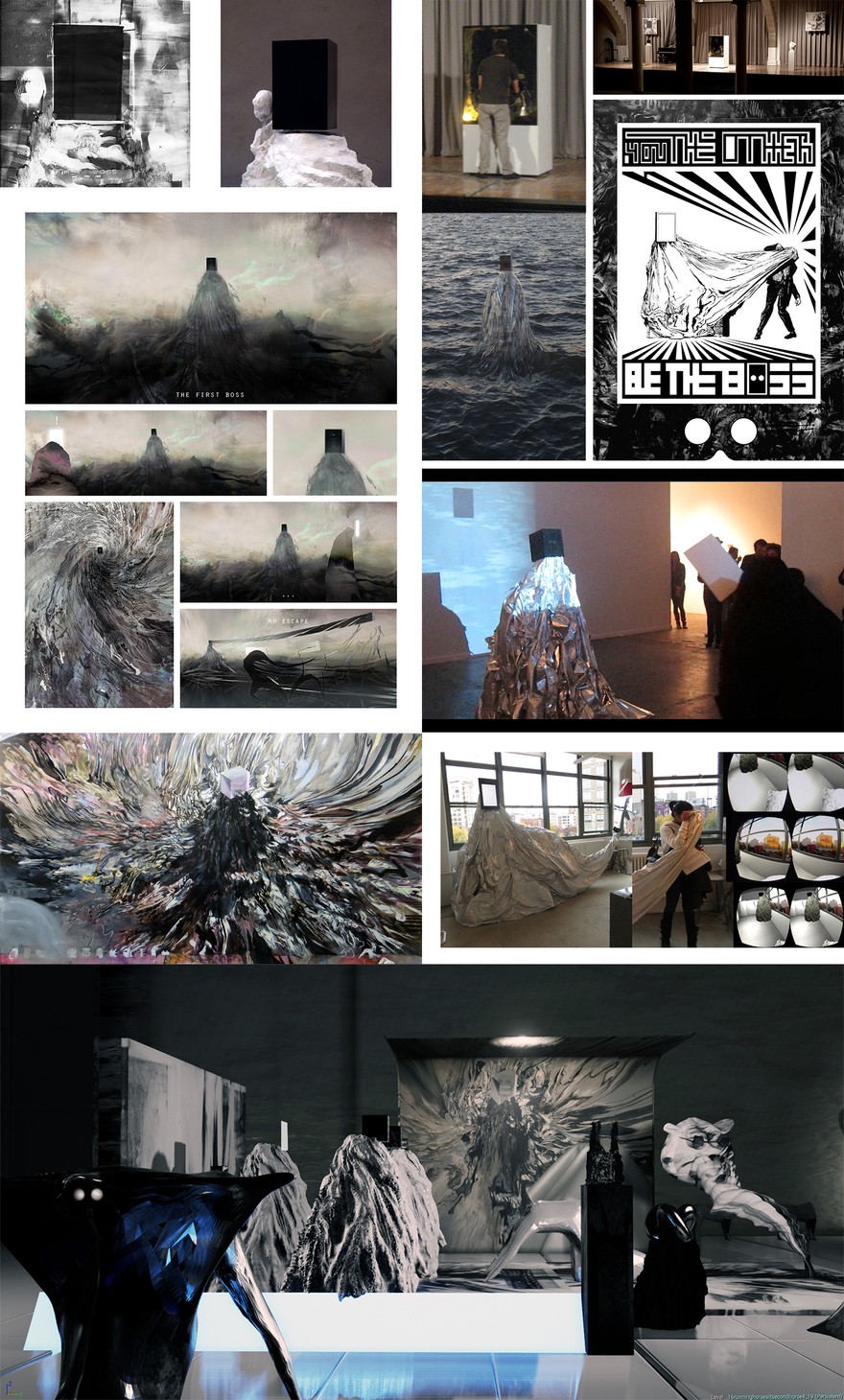

With this in place, Castaneda was able to put bristle to paper and explore his whimsy. He filled in the “Levels” and “Bosses” (as well as sub-levels such as 1-2, 1-3) with images that suggest rather than describe: forest maps made of triangles, mountainous swirls of dark paint, symbols etched as architecture or depicted as gods. Whatever took Castaneda’s fancy on that particular day became the representation of that Level or Boss. And such range it has resulted in, as best sampled by a quick overview of his bosses: “from one resembling the monolith of 2001: A Space Odyssey, to a sandwich shaped building, to a cathedral/factory hybrid, to a ‘Boss’ that is one of my undergrad professors,” Castaneda said.

What Castaneda perhaps didn’t expect, at least not at first, is that his project would lead him toward a deconstruction of these videogame structures. He recognized that the hierarchies and layouts of these labelling systems aren’t specific to videogames. In fact, Castaneda traces it back to the mythology found in most cultures, in which a pantheon of heroes and gods are usually arranged in terms of power and lineage. “One finds these structures of a parallel reality where beings rule over locations and each other,” he said. He found it in Hinduism, Christianity, and Buddhism, and also in Greek and aboriginal mythologies. Comic books and anime have also replicated these systems into their imagined societies. While in our modern day realities we’re familiar with corporations arranging people by their rank, from president to CEO.

Making this observation is perhaps why Castaneda was compelled to branch out from the boundaries of painting and take his project to multiple disciplines. Still sticking with those videogame structures as his glue, Castaneda has since dipped into sculptures, performance, virtual reality, and conceptual art. His implied landscapes and terrifyingly abstract “Bosses” have emerged from the flat environments that they rule over on paper, and have been made 3D and interactive over the years. Often it’s the case, particularly in his virtual reality projects, that Castaneda has the viewer experience the perspective of a Boss in order to “to challenge the treatment of the Boss in more inclusive ways.” This is born out of noticing that videogames place the boss strictly as an antagonist in their narratives. He wanted to confront that tradition in order to have the viewer connect at a closer level with his work.

Now, with this catalog behind him, Castaneda seems to be looping back on himself: “since the structure is based on that of the videogame, all works that I’ve made in the last 6 years of working on the series can become a blueprint to an actual game.” And that might be what it eventually leads to. For the past couple of years, Castaneda has been learning how to use game design programs in order to bring his paintings into the virtual world. This has led to something. “I hope to make a videogame-only/virtual reality experience based on all the ‘fine art’ works that preceded it where the structure of games is broken down and thrown back out towards greater possibilities,” Castaneda said.

At the moment, Castaneda is pre-occupied with translating the panels of a comic book he made for “Level One” into Unreal Engine 4 in order to see what the consequent game world would look like. Once that’s over, he reckons all he’ll need is a lot more training or a small experienced team to get the first chapter up and running, completing the cycle of inspiration from videogame to painting and back into videogames once again.

See all of Leo Castaneda’s work at his website. Also check out his Levels and Bosses blog.

///

Header image: Level One Panorama, 2011, Leo Castaneda

Lower right image: Prototyping Level One, 2015, Leo Castaneda

Below: Lineage of the “First Boss”, 2009-2015, Monoprint, sculpture, comic, photography, performance, virtual reality, painting, Leo Castaneda