Depths of Fear: Knossos is an interactive B-movie

Labyrinths are an enduring preoccupation. They’ve inspired the literature of Jorge Luis Borges and the art of M.C. Escher. They’ve provided Plato, W.H. Auden, and Stanley Kubrick with potent rhetorical symbols. They’re even responsible for a collaboration between Jim Henson and David Bowie. Just the same, the foundation of the labyrinth myth can be boiled down to something without any grand artistic connotations: a warrior setting out through a twisting maze and, upon reaching its heart, fighting a monstrous bull-man to the death.

Depths of Fear: Knossos is a videogame that embraces the latter understanding of the labyrinth. Developed by one-man studio Dirigio Games, Knossos is a send-up of the action movie interpretation of Theseus’ triumph over maze and monster. It doesn’t waste time intellectualizing or using the myth as a starting point for some greater discussion of unfathomable mysteries. Instead it filters the labyrinth story through the dual lenses of infinitely replayable “roguelike” videogames and no-budget B-movies. It’s a playable version of those dusty VHS tapes at the back of the video store with cool monsters on the covers. Knossos boots up to the sound of analogue crackle and pop, a thunderous drum roll, and then a hammy Carpenter-era synthesizer swell. Moments later the player, looking through the eyes of Theseus, surfaces from a pool of water, gripping a torch and preparing to delve into the dimly lit passages of a Hellenistic nightmare.

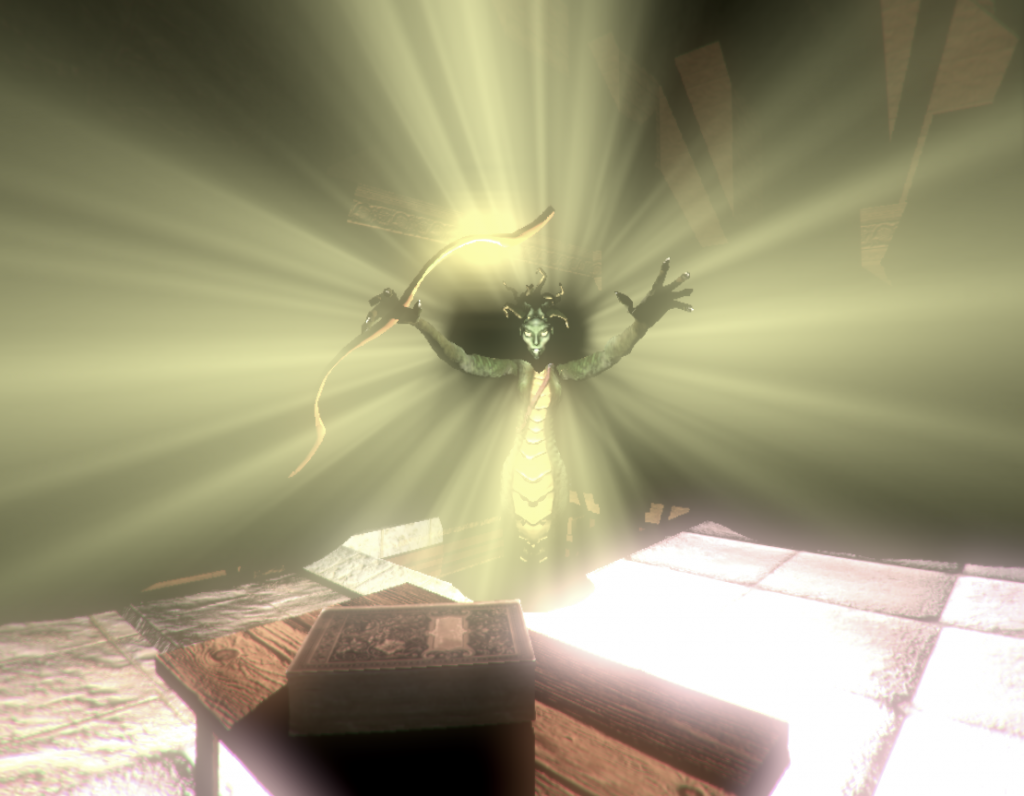

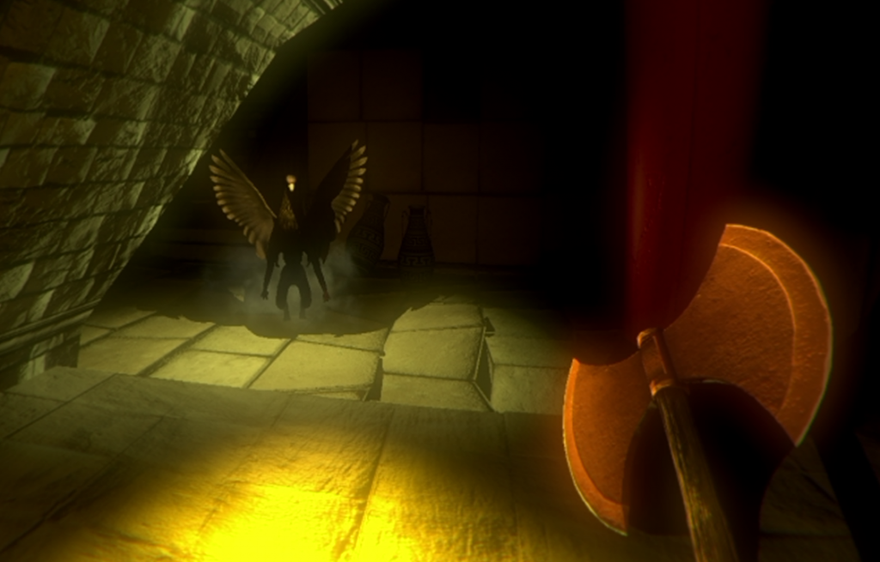

The objective is clear: kill the various monsters—Hydra, Cerberus, Medusa, and so on—lurking in eight different mini-labyrinths in order to unlock the only sword capable of striking down the dread Minotaur. Collect gold coins to buy ancient weaponry. Navigate the darkness of the maze, alternately hiding from and murdering Grecian beasties, and end the story the way it’s always been written: heroically. Survive and thrive, Theseus. Dirigio Games’ death-laden, respawn-centric take on the heroic myth is an appropriate one since the roguelike genre itself, with its reliance on unpredictable geometry and imminent danger, owes a lot to the concept of the labyrinth. The only way to win is to explore the ever-changing landscape as fully as possible and to always prepare for whatever threat must be looming around the next corner.

Dirigio Games has made the most of its lack of resources by embracing its limitations.

This emphasis on repetition and constant peril isn’t Knossos‘ defining trait, though. It’s campy, sometimes even a bit scary, but mostly kind of funny. Its lo-fi visuals—a stiffly animated throwback to the early days of polygonal videogames—are endearingly silly. The monsters may not be all too frightening up close, but coming across one of them, growling and repeatedly butting its head against a barrel in a dark passage due to a programming hiccup, has the same kind of charm as the stop-motion skeleton legions of the 1963 Jason and the Argonauts. This aesthetic is reinforced through Dirigio’s score, a collection of minimalist synth tunes that set a wonderfully offbeat tone. The music is deliberately dated, conjuring exactly the era of unconvincing special effects and VCR tracking lines it looks to evoke. The sound design, together with the PlayStation One-style graphics, give Knossos a surprisingly confident look and feel. The game’s presentation may be shoddy by virtue of solo development, sure, but, even if that’s the case, Dirigio Games has made the most of its lack of resources by embracing its limitations.

It’s hard to be too enthusiastic in celebrating the virtues of a game that is so difficult to actually operate on a moment-by-moment basis, though. Theseus’ first-person movement is far too imprecise for what Knossos wants to accomplish. Swinging a spiked club or throwing a spear at an enemy has all the impact of a zero-gravity pillow fight; climbing a simple ladder is a game of chance where one result is a predictable dismount and the other is a quick fall back to its base; even the act of picking up a key, potion, or coin can take several button presses to perform. In a game where brushing up against a monster so often results in instant death, inconsistent controls are hard to forgive. Crummy visuals and a schlocky tone can be fun but, much like a B-movie with lighting so poor that the viewer can’t discern what’s happening on screen, botching the fundamentals of a medium makes it tough to eke much enjoyment out of the experience.

When Knossos is getting things right, it is a game so confidently peculiar that it’s hard not to find endearing. More often than not, though, the actual act of engaging with its design obscures its best features. The game’s recurring monster encounters offer perhaps the best encapsulation of this problem. Theseus sneaks through the darkness, carefully picking his way through trap-filled rooms by the meagre light of a torch. In the distance the sound of goat hooves clap across cobblestones. The player’s heart hammers as the beast catches sight of her and the scuzzy chase synths kick in. Then Theseus is running through the labyrinth, the player steering a body that moves like a sailboat. The monster closes in, but the exit to the level is within reach. Theseus tries to jump down the exit staircase and clips into the opening. The player maneuvers him back out by hammering on the keyboard and wiggling her mouse around frantically. But it’s too late. The monster wiggles into frame, Theseus swishes his sword around ineffectually, and any hope that the enjoyment of the last few moments can maintain coherence is swallowed up by the realization that the game is simply functional. Knossos loses itself, ultimately, in a labyrinth of disjointed failures.