In a fort I find a bell and hang it up. Ringing it sounds a sudden death knell and plunges the world into darkness. It continues its eerie ring, and the world whispers around me. I quickly mute it. As my eyes adjust to the light, a hooded lady in red suddenly appears in front of me; I turn and flee. I notice a pile of loose dirt from my hiding place. Buried is a single, disembodied ear. I’m confused, lost, and scared.

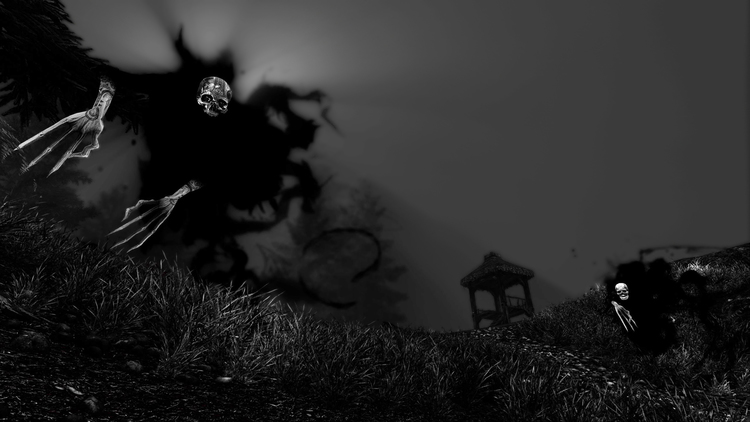

This point, the very beginning of the game, was when Betrayer felt at its strongest. I was in awe of the beautiful monochromatic world, with its raw, violent splashes of red. Exploring the forts of an abandoned 17th century colony felt novel, felt exciting! Spanish Conquistadors barked, totems moaned, and I had an errant tongue in my inventory: Betrayer spoke to me in a beautiful, dead language.

But then I started to parse its meanings.

Ostensibly, the game is about reconstructing the tragedies that befell a deserted English colony in Virginia. Each forested area contains buried clues that piece together a complete picture of events. You’ve got your ghosts, your Conquistadors, and a mysterious archer with a heavy dose of amnesia. In other words: Whodunnit?

Tantalizing as that question may be, Betrayer doesn’t actually progress this core mystery until the very last hour or two of the game. Each fort and settlement house their own disparate stories, usually with little layover. These tales are worth a grimace, gruesome as they are, but they don’t do much to provide a throughline for the whole shebang.

Betrayer’s ceaseless clue fetching is, on the surface level, no different than a game like Gone Home. Both involve picking up objects in the environment and using them to learn about the characters they belonged to, but Betrayer fails to cushion its storytelling mechanic within a persistent context. Storylines begin and end in one area. I, as the backstory-less main character, have no stake in the fate of the colony. The sole constant character (aside from a merchant) doesn’t see any kind of development until the core mystery is already wrapping up. After the first two levels the feeling of being some kind of bow-and-musket wielding PI dissipated. Instead, I started to feel like a squirrel who forgot where my acorns were buried, so scattered were my attentions and so routine my tasks.

The combat end of things follow a similar trajectory, from expansiveness to routine. Initially the game revealed some intriguing tactics, like using gusts of wind to cover my footsteps as I ran. I bought into the stealth mechanics and stalked the forests cautiously, crouching low and taking pot shots whenever I heard the telltale growl of a Conquistador. But then I realized that there’s no reason not to be blasé with Betrayer’s combat. Its nuances faded as I gained more powerful weapons, got a handle on the floaty mechanics, and figured out that most enemies drop after taking two arrows. I made those acquisitions early on, and Betrayer doesn’t attempt to mix up the experience much: weapons operate roughly the same; there are a handful of different enemy types, most of which I could dispatch in a casual drive-by as I headed to my next objective. Combat became negligible.

The one aspect of Betrayer that didn’t eventually leave me out in the cold were those stark aesthetics. This game’s audiovisual experience is like a bottomless pint of ice cream, that, accordingly enough, got me sick when I couldn’t stop gorging. Developers Blackpowder Games include a slider in the settings so you can add as much or as little color as you want to the environments, specifically to stop people getting the spins. I never switched over, though, even to address whatever part of me was being thrown off by the monochrome. Sprinting across a sun-drenched empty field, listening to the wind brush through the greyscale grass underfoot, felt downright transportive.

But Betrayer doesn’t take full advantage of its beauty. Think of climbing a tower in Assassin’s Creed or even walking up to a house on a hill in Alan Wake: the camera pans out a touch (or a lot in the case of AC), framing the moment just so as you move through it. These are points where you savor your surroundings. You relish it as a complement, as a change of pace from the inherently fast paced nature of doing something with which you are deeply engrossed, whether shooting dudes or listening to an audio diary. A videogame’s aesthetics are best enjoyed when intertwined with engaging content.

This is not the case in Betrayer, as its mechanics and narrative grew routine. I appreciated those aesthetics only from a distance it wouldn’t give me. It’s hard to criticize a game for being good-looking, but it’s hard not to when its ambitions so clearly lay beyond that.