Ever obsessively played Doom? This is probably what it looks like in your dreams

Doomdream is more of a description than a title. It’s an attempt by its creator, Ian MacLarty, to conjure up an “impression of [his] dreams after [he’s] been playing Doom all day.” That’s Doom, the 1993 hell-romping shooter, which mostly everyone is familiar with. If you’re not, all you need to know right now is that its levels are typified by asymmetrical labyrinths with low ceilings and forking pathways that often loop back on each other.

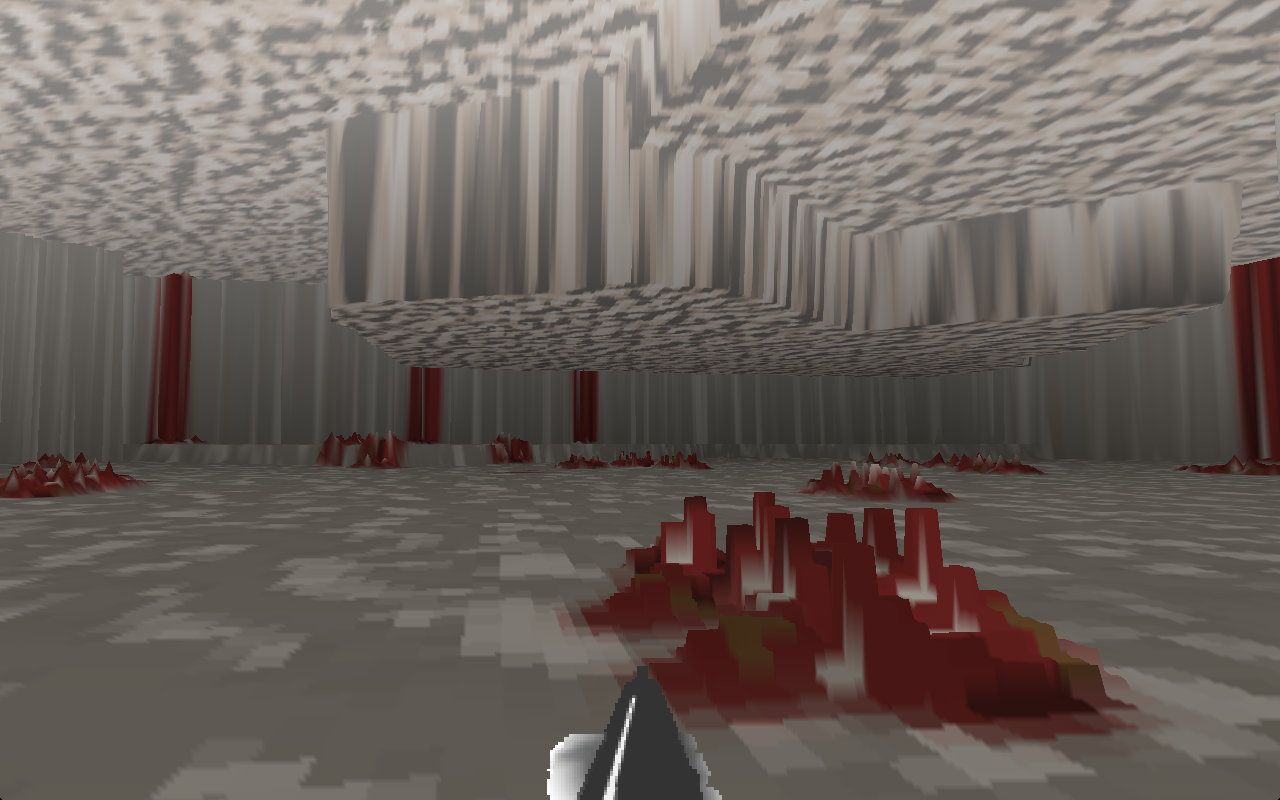

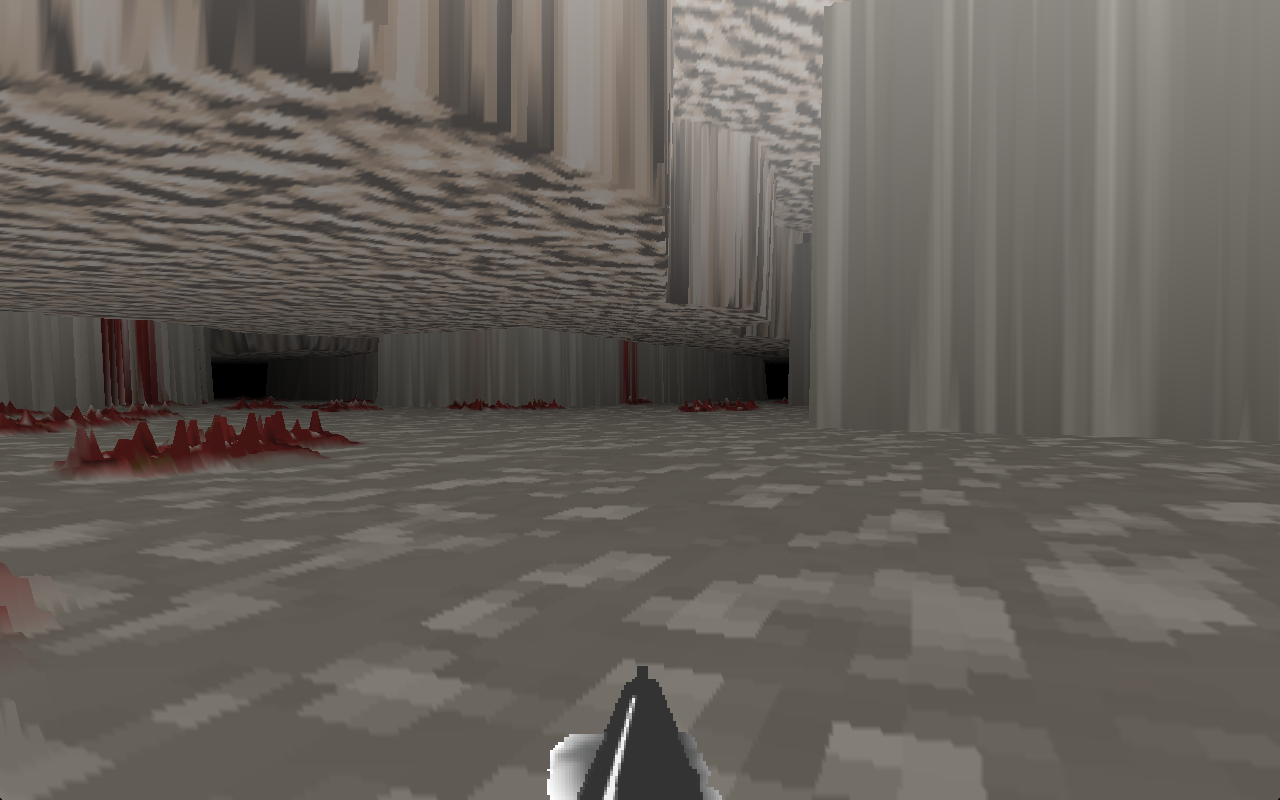

It’s this architectural theme that Doomdream replicates, sans the spike-skinned imps, and biomechanical texturing. It’s entirely white, grey, and red: the colors patterned as grainy pixels, or stretched vertically to form walls that appear to have seen carnage thrown against them (the red in particular looks like smeared gore). As per Doom‘s twisted sci-fi facilities, the ceilings and floors are staggered at different heights, the separate pieces of geometry obvious to the eye with sharp drops and steps up.

eager to get out of that repeating terrorspace

Doom had this jagged appearance due to the limitations of 3D level design at the time; lots of slopes and smooth edges just wasn’t viable. Here, abstracted as it is in Doomdream, it highlights the immediate violence of Doom‘s unfriendly labyrinths, the empty volumes being cut into by saw-tooth structures.

But that’s not even the focus of Doomdream. MacLarty tells me he “based Doomdream on being lost after killing all monsters, unable to find the exit—just a maze of abstract architecture.” Indeed, it’s part of Doom that isn’t often discussed despite it more than likely being universally experienced. That’s on account of it being the more frustrating part of Doom‘s labyrinthine level design, at least from a player perspective, as you circle the same tunnels looking for the coveted “EXIT” sign.

Even so, it’s an essential part of its horror. After all the monsters are slain, pocking the ground with exposed ribs and pools of blood, you’ve only the maze for company. It’s then that the imposing architecture and its ability to to confuse and lose you gets to shine. You’re eager to get out of that repeating terrorspace, and the fast movement speed should make that a quick goal to achieve. But it isn’t, and in fact, the blistering movement speed only adds to the muddled panic. You travel Doom‘s tunnels as they curl round to unseen rooms, or to nowhere at all, meeting at dead ends. It’s like you’re trapped inside a bronchial tree. Its spatial complexity and interconnected corridors causing you to pace the same territory accidentally.

MacLarty theorizes that, due to the growing fear and frustration of these moments, your brain makes an effort to absorb the forms you rush through into its mental capacity so as to easier navigate them. Perhaps this is why MacLarty revisited these spaces in his dreams; “I think it’s the brain’s way of making a mental map of the game world,” he says. The tumultuous act itself has a particular dreamlike quality too: I’ve had countless nightmares of feeling lost, stuck in a place that loops itself until it feels unending, as if a sinner’s punishment in Inferno.

It’s not just Doom that has this effect on our minds either. As we found out before, videogames and especially abstractions of them have a way of staying with us into our dreams. Bob Stickgold, an associate professor of psychiatry at Harvard University, researched this and previously told Game Informer that it seems the high emotions that videogames draw from us could cause our brains to repeat scenes from them during sleep. There’s no concrete evidence to be able to say that this is exactly what happens. But it does mean that we can lock Doomdream firmly away into the evidence locker that suggests it is.

You can download Doomdream from itch.io.