Rumors from the forlorn: An Eidolon Review

After dedicating 1845 to 1847 to “simple living” in the woods, avoiding all human contact, Henry David Thoreau explained himself with a classic line of transcendentalist reasoning: “Not until we are lost do we begin to understand ourselves.” Thoreau was the kind of deep thinker that claimed to get drunk on breathing the air around him; a vegetarian, abolitionist, and in a constant love affair with nature, he was said to reside in a pastoral realm that straddled wilderness and civilization. It was this middle ground that granted him, or so he thought, the ability to perceive the essential facts of life that allowed him to find “eternity in each moment”—eternity, here, being a rare didactic timelessness.

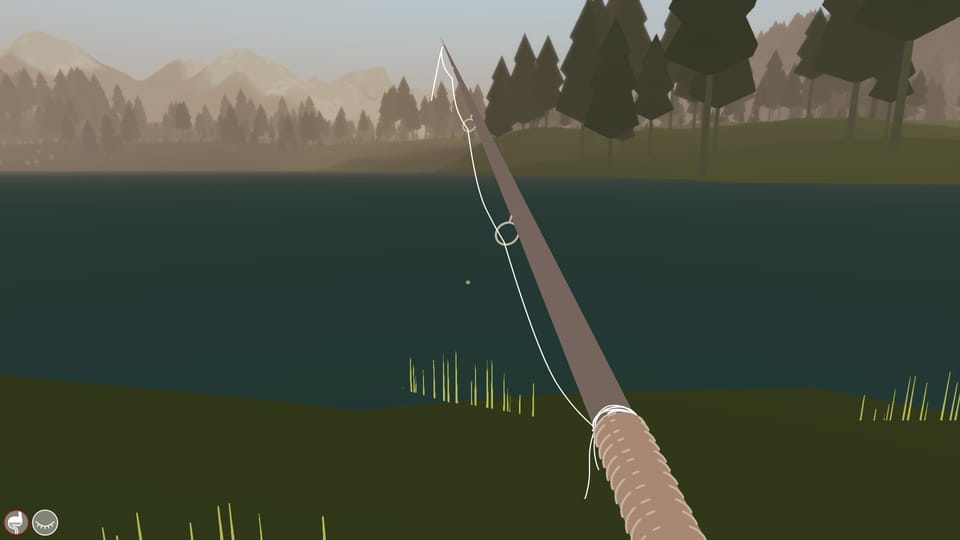

Thoreau’s hermit paradise is what balloons out from my first steps into the wild expanses of Eidolon. Around me is a love letter to the wilds. The game has an appetite for momentary vistas: morning mists hang gloomily over lakes like a warning; through the binoculars, a view of foxes playing at a mountain’s foot; a gold-dust night sky gnawed at the edges by ghastly silhouettes of cenotaphs and crooked branches. I aimlessly march across this routinely poetic expanse, guided by the uncertainty of compass navigation and a question: “Where am I?”

my immediate ascension to emperor of this gross necropolis.

The way the title screen fades away from menu to first-person view has the subtlety of Eidolon‘s day falling to dusk. It draws me into the world as easily as if it were part of my breathing process. This peace of mind is only mildly let-up by the anxiety of wilderness survival, moreso by the occasional glowing diamonds that hover along my eye-line. They distract from the fidelity of Eidolon’s beauty with the overt lexicon of a videogame. I only put up with them as they steadily fill my journal with arduous tales of the land’s long-deceased passengers, adding to the forlorn mystery of the triangular debris and unnamed gravestones I come across.

Enthused by the sights, I compulsively snap screenshots when the trees and lakes align, and I celebrate my findings into the journal I’ve been supplied. Living this Boy Scout’s existence has me feel entirely human at times. When settling down next to a bonfire after tucking into a dead fish I caught, staring up at the star-punched holes in the night sky, the joie de vivre comes to tuck me in. But then I commit the ultimate betrayal against this solitary lifestyle.

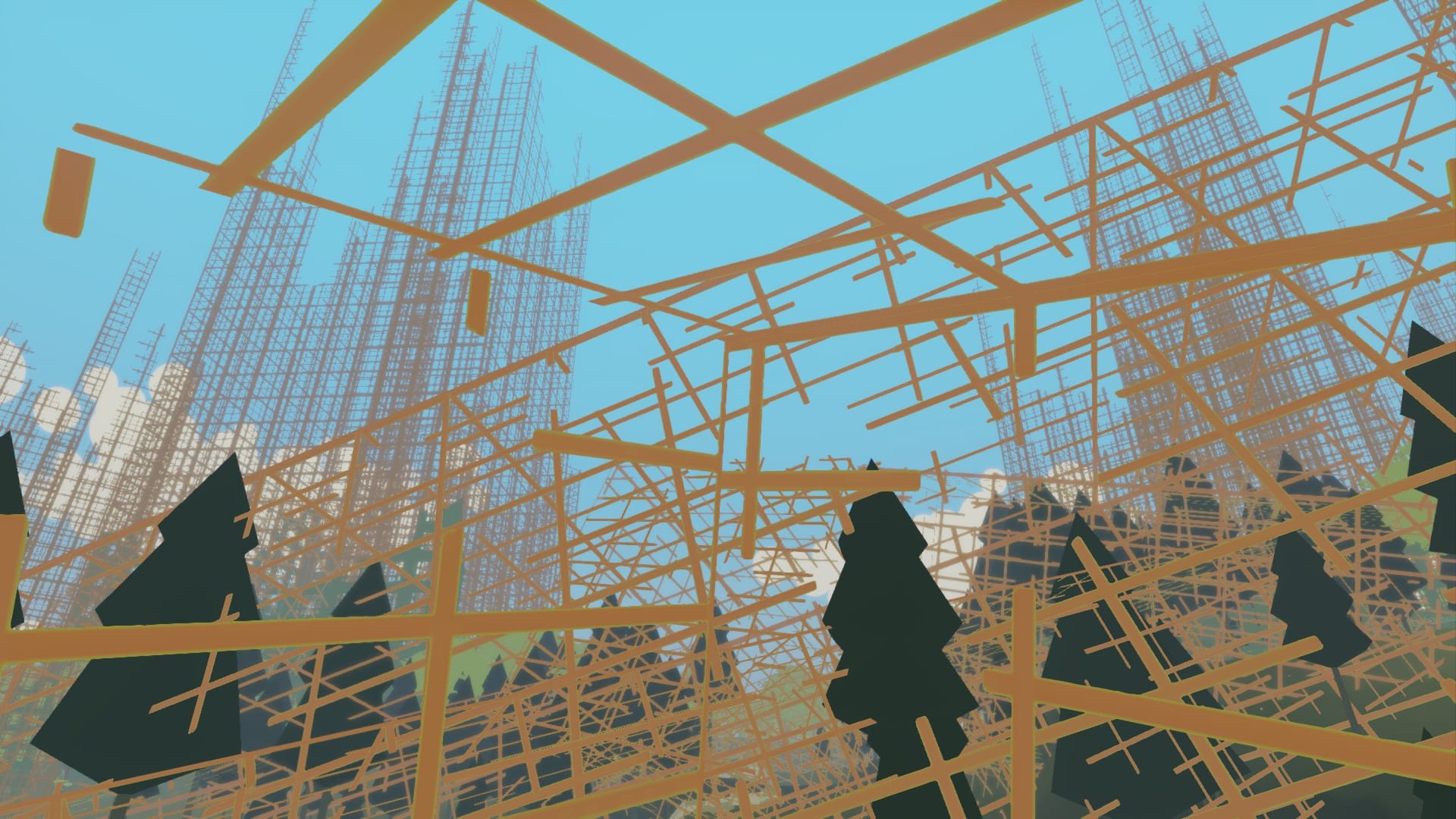

Proud of my screenshots, I chose a couple of the best to share on Twitter for reciprocation’s sake. What’s the use of all this beauty if I can’t share it with someone? But that’s entirely the point: Eidolon‘s post-human Washington becomes your personal Garden of Eden—you pay for it in loneliness. Perhaps I had gone stir crazy, but it seemed to me that a tremendous karmic force had swept through the forests of Eidolon when I returned to it after my break with social media. I noticed that the trees suddenly started repeating their formations as if to dullen the magic that had previously entranced me. “Move on, nothing to see here,” it seemed to be saying. I stay, but the trees then stack on top of one another as if to intimidate me with sheer size. This glitch finally prompts me to leave; I fear the forest further spoiling itself.

My departure was timely. Upon exiting, I look back from the fringe of the forest to see a deer with its whole head swallowed by a tree trunk, its legs stuck in a back-pedalling animation. This must have been what Thoreau saw when heading into the “real wilderness” of Maine. In “Wilderness and the American Mind,” Roderick Nash describes Thoreau’s 1846 trip to Maine as affecting him “far differently than had the idea of wilderness in Concord. Instead of coming out of the woods with a deepened appreciation of the wilds, Thoreau felt a greater respect for civilization and realized the necessity of balance.” I, too, craved civil surroundings, and found myself curious of what had become of the cities marked on my map.

Be it no surprise, then, that I head north-west into Bellevue after emerging from those peculiar woods, pursuing a deceased industrialist I read about in a decaying newspaper. It was here that I found the grimness of Eidolon‘s Washington, particularly in the fossil-cars that dotted its drooping highways. “Welcome to Bellevue,” a sign should have read, “the ultimate in shopping, dining and cultural attractions.” Further in, I found only the chaotic meshing of collapsed scaffolding that once stood tall as buildings, but is now a huge rusted ribcage for the mass piles of skeletons that rest without ceremony. Not even the ghosts are left to haunt me. The rule of default granted my immediate ascension to emperor of this gross necropolis. Tears For Fears sang “Everybody Wants To Rule The World,” but I’m sure that they didn’t envision this depressing scene. If the game allowed it, I would have dropped to my knees and re-enacted the painful scream of denial in the twist ending of Planet of the Apes.

the ghostly implications of a vampire that has no reflection.

With no one around and nature seemingly eating itself, I resolved to the only thing left: death. That’s what prior exploration games have always taught. Proteus had us float heavenwards as our eyelids shut tight; TRIHAYWBFRFYH crushed us with the falling of the sky; Miasmata had us die from illness or miraculously escape from it to die another day. Some form of a release from life, a closure, always snatches us away from these virtual worlds, whether we want it to or not. Exploration games divulge the knowledge that humans are unique creatures in that we can reason that we are going to die, but can also imagine life going on forever. Our time in them is cut short so that our appreciation of them lasts forever. They’re blissful vacations rather than life-long marriages that turn sour and end in angry divorce. It’s this that Eidolon completely inverts.

Its fundamental systems suggest the needs of the body: to eat, to rest, to be warm, to resist illness. There are small icons that flash red with skulls and stomachs if any one of these is neglected. I hunt, fish, and forage, collect tinder, and avoid large falls as well as swimming for any great length in the cold lakes. Every notion of my being in Eidolon is crowned by an intimate fear of death, yet it needn’t be. The need to survive is a phantom limb. Die in Eidolon and you reappear nearby in a grotto surrounded by playful nymphs, as if waking from a drunken slumber. Unlike the rest of humanity, I can only dream of death as I live perennially.

Eidolon begins to shift from sensual spiritualism to the crueller realm of sci-fi forewarning and philosophical experiment. Thoreau’s “eternity in each moment” is no longer just a celebration of rare beauty. I now realize that I virtually embody it: I am eternal. Ice Water Games always intended for this subtext to emerge over time. Eidolon means “an idealized person or thing,” but it also can be used in reference to “a specter or phantom.” Perhaps I am both. It rings true in how I am forced to live forever on the fringes of humanity, and the way the map never states “You are here” has the ghostly implications of a vampire that has no reflection. Thoreau would have us believe that this state of being lost between two dimensions leads us down a path of introspective understanding—after all, I am lost and now seek to understand myself. At least in the case of Eidolon, he’s right: I found myself trying to unravel an immortality I never asked for.

Perusing the only materials I had at hand, a moment’s thought gives me pause while reading a letter sent to Father Jerome in 2021. It’s begging the Father to consider a new technology that prolongs the years of human life, “not as the temptation of the apple, of Satan himself, but instead as the donning of the mantle of Methuselah and the Patriarchs.” The letter suggests that it’s about time that God rewarded humankind with the gifts it bestowed upon the Prophets of old, such as Enoch (who lived 365 years) and Methuselah (who died after 969 years). Am I a prophet?

Nature becomes a backdrop to a laborious treasure hunt.

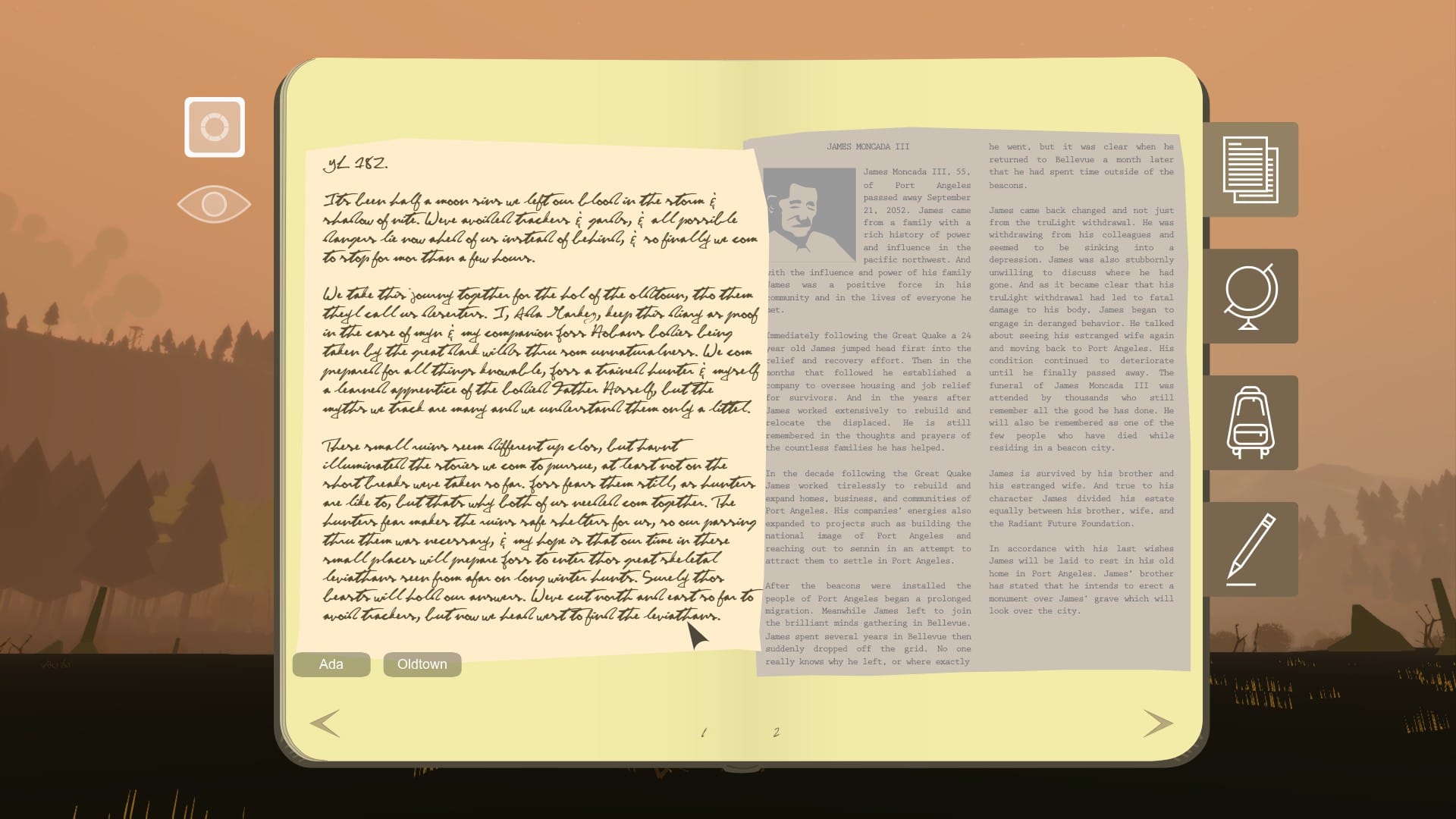

Struck by the idea of my eternal life having a higher function, a relationship between myself and the papers scattered around Eidolon‘s world takes over. Occupying the thoughts of the many lives that I read about are questions that purvey every religion and philosophy—the big ones: the meaning of life, what comes after death, what it would be like to live forever—and they’re all looming toward me. Rifling through these historical journals and electronic diaries I find the final utterances of regretful world-destroying industrialists, families fleeing earthquakes on packed highways, heads of churches arguing for a traditionalist regression. Many of them strike me as the same hopeless narrative of a species stuck on a loop: God-fearing Ada Markez writes in angular shorthand to detail her desertion from Old Town to find the answers she seeks from the leviathans—she never found them.

Others aren’t stories as much as they are evidence of humanity’s entrenched necessity to go for each other’s throats in the name of manufactured immortality systems: Anath Nair’s essay dated November 15th 2063 discusses his will to find Svarga on Earth despite a growing conflict between Hindus and the “Beacon Project,” which was a science program that aimed to achieve eternal life. Chasing and consuming these bits and pieces that have survived the burn of time gradually forms a patchwork timeline that falls through my fingers as I sift through it. More questions about me and of humanity’s impermanence are raised but no answers are even vaguely entertained.

Despite the insight into humanity’s downfall that these piece-by-piece narratives offer, they also override Eidolon‘s greatest strength: the compass and map are thrown out for deadly accurate waypoints. Names of places and people underscore each document I find in the form of buttons which, when pressed, send out a flurry of green shards that lead directly to the next residual piece of each story. Nature becomes a backdrop to a laborious treasure hunt. This paper trail has the sense of purpose that I’ve been craving, but it’s grossly unfulfilling once the novelty has worn off, like getting a dream-job after years of pining for it. The activity’s drawn-out repetitiveness—journeys that take in-game days to complete—leads to ennui if not managed in short doses. It’s the same experience I had when engaging in a streak of relentless completion of hundreds of side quests in Batman: Arkham City (and most other open world games). The intrinsic pleasure of exploration on my own terms has been spoiled by the empty incentivization of collecting these documents—an “overjustification effect.”

It was better when I acted oblivious to these waypoints and explored because a certain distant light caught my fancy, or a landmark beckoned, or I heard the distant footsteps of the dead. What’s left just makes me anxious. What are these people’s stories but the attempts of old souls trying to live forever through memorial? Humanity and its greed—its warring nations, its endless pursuit of technological perfection, and not forgetting its insatiable thirst for immortality—has devised its downfall. Stephen Hawking said, “It is not clear that human intelligence has any long-term survival value.” We went after it all and lost everything. As far as Eidolon is concerned, only nature in its unquestioning tranquility is worthy of immortality. All I’ve been doing is chasing questions without answers, allowing humanity to leach a prolonged existence through my living memory. The only question I might possibly answer now is whether or not an existential boredom settles in if you live an endless life for long enough. Eidolon suggests that the answer is yes.

The prospect of fresh exploration still holds a spell over me

The only thing left for me is to retire to the wild hammocks of the woods. But before I do, like the old fool I am, I grant humanity a last chance at redemption. From noon through night I’m led ever closer to the edge of the sea by the journal of a pilgrim called Triya. She’s travelling with an older companion, Elden, who hopes to find a rumored cure to Beacon addiction. Her words are affectionate to her reader; she shares her most vulnerable thoughts.

Arriving at the brow of the ocean, I discover that Elden found a sailing boat that’ll get the pair to a peninsula I cannot reach. Before they head off, Triya says her goodbyes, adding that she’ll still write letters when she reaches the other side, and urges me to look out for them. “I hope you find whatever it is you’re looking for,” she says. Putting her last letter away, I’m surprised to find that the next set of guiding shards I send off into the sky prompts me to head out towards the watery horizon, as if to top myself once and for all. The old thought comes back: “If only I could.” But that these shards were able to point me towards anything at all has another suggestion for me to ponder for one last time.

I wonder if the world is still out there, if there is anything else left at all. The prospect of fresh exploration still holds a spell over me, but it is not to be found on these lands any more.