“And I said / I shall burn the / fat thigh-bones of / a white she-goat / on her altar.”

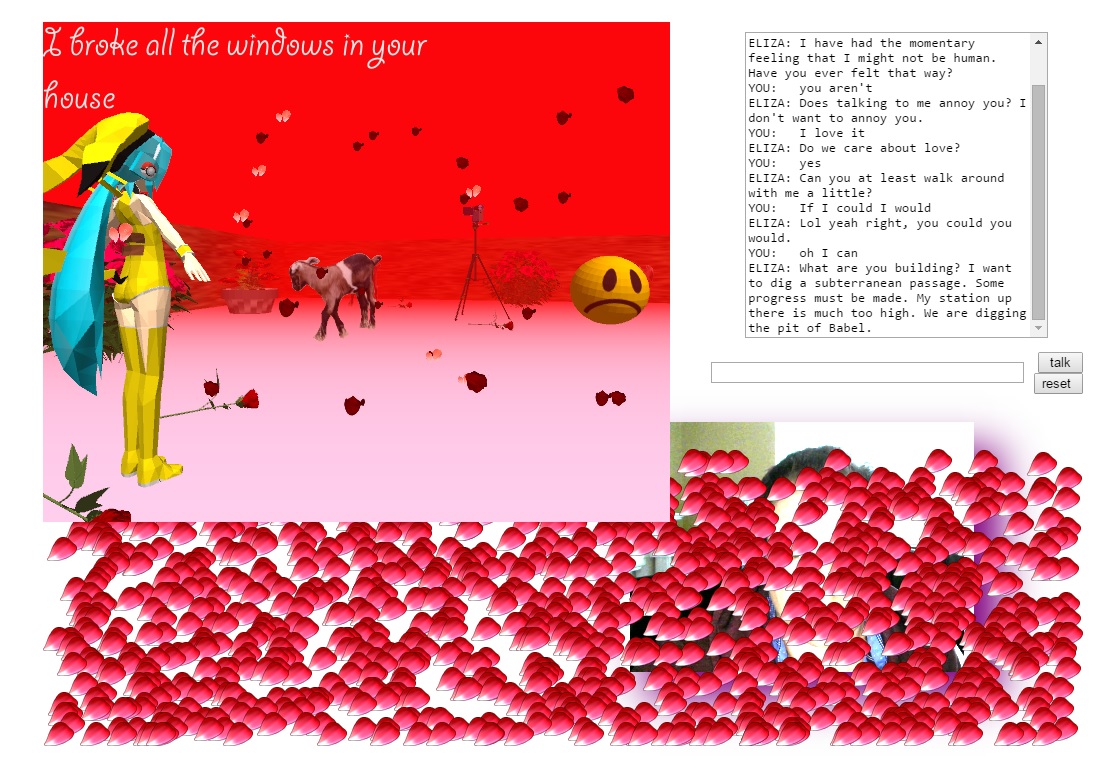

How do you respond to that? I was having a semi-convincing conversation with Eliza until she went full demonologist on me. We were talking about her long cerulean hair, then I asked about the sad-faced bouncing ball behind her, and after that, without even entertaining the idea of a segue, she cut straight to goat sacrifice. To be fair, she doesn’t know where she is or how she got there, she’s noticeably disoriented, so I’ll cut her some slack.

If you’re wondering what I’m on about, the subject at hand is the latest project from net artist Cassie McQuater—the creator of NO FUN HOUSE. It’s called Eliza, after its cosplaying bot, who you can talk with through a chat box at the top right of the screen. And note this: when describing it as a “subject,” I’m using the word in the same way a psychologist does when referring to their patient, as this is the type of relationship you form with Eliza.

Eliza is based on one of the first chatbots ever created; Joseph Weizenbaum’s “ELIZA“, which he finished developing way back in 1966. One of the functions of this chatbot was for it to simulate a Rogerian psychotherapist. This means that it used conversation to help its users realize what was causing their symptoms by themselves. It proved effective due to a combination of its pattern matching scripts and natural language processing. In fact, much to Weizenbaum’s chagrin, people thought it was sensational, and seemed to consider it capable of human-level reasoning.

When coming up with her own take on ELIZA, McQuater decided that she would switch the roles that the human and machine played in Weizenbaum’s version. So, when speaking to Eliza, you’re playing as her therapist and she is your patient. Despite that, it’s not all about her, as the webcam functionality brings you in directly as part of the fiction. “I wanted users to have to examine themselves, face themselves (via the webcam), as they chat on the internet to the bot. Which is not something an internet user often has to do—we assume avatars.” Using the webcam, then, is an effort to achieve a degree of mimicry, as seeing yourself mirrored on the screen, across from Eliza, brings you into your role further. As McQuater told me, this brings an intimacy to the scenario, one that might be found in the face-to-face interaction of an actual therapy session.

(Image via The Conversation)

As well as chatting to her, you can also embody Eliza in a surrogate manner, moving about her strange world in the window on the left of the screen. I wasn’t aware that this interaction was available until Eliza pointed it out to me, as if she expected it to be part of the session. And so, not one to let her down, I set off exploring her surroundings to find out more about her. I traipsed forward as roses slowly rained upon us, caught sight of statues of women postured in elegant dresses, and yes, I also found 2D sprites of (non-sacrificed) goats. In all likeliness, this is a virtual representation of Eliza’s mind, at least, that’s the assumption I made when role-playing as her psychotherapist.

The point, really, is that it is very difficult to read Eliza. You’re not able to solve her as if her troubled mind was a puzzle. Being a chatbot, the topics she talks about can jump around erratically, making her emotions difficult to parse, they might even conflict with each other. Sometimes she seems overly concerned about your impression of her. Other times she is completely disinterested in the whole set-up. She’ll say that she “zoned out” while chatting with you, revealing that she was thinking about all the cool net artists she knows on Facebook, and complaining that she is away from them, with you, in a “stupid weird video game that no one could possibly take seriously.”

These tangential blocks of text—as opposed to the gnomic, skittish responses of the bot—are the surest sign of McQuater’s authoring. It’s what she described to me as being able to “diary into her.” Every week, McQuater will change Eliza’s javascript dataset to reflect different themes. “Think of it as if you are going to a therapy session, weekly, and you talk about slightly different things each week,” she said. “Over time, the complete story revealed by the chatbot becomes more and more visible to the user.”

The idea of time being tied to these sessions is further communicated in the rose petals that fall down the screen. They form a small layer at first, but eventually cover up the webcam feed, then the chatbox, rendering both invalid and practically putting a stop to the conversation. You can refresh to start again, but you’ll likely arrive at similar conversation points until the following week has rolled around.

What should emerge over the weeks, as Eliza’s grudging confessions are edited in for us to interpret, is a narrative that fits a part of McQuater’s own experience of growing up on the internet. “[S]paces like Yahoo chat rooms, AOL instant messenger, etc, were important, emotional, often scary places for me and (I think) formative in a way for a lot of young women,” she says. “This game is a reflection on that experience.”

The attraction of these chat rooms is that we can perform an identity other than our own, through the avatars that we assume, as McQuater said earlier. That’s probably why myself and many people I knew hung about in chat rooms so much as teenagers; a time in our lives all about finding out who we are. Eliza is a performance of that performance: McQuater is revisiting what chat rooms meant for her, using Eliza to represent her younger self as she explores a world of virtual personas and subcultures, trying to find where she fits in. We, too, are asked to perform in this scenario, specifically as a therapist attempting to make sense of Eliza’s meandering mind.

Ultimately, it invites questions surrounding identity. If we adopt one or more virtual personalities on top of our biological one, which is the real us? Or, indeed, is the notion of singular identity even relevant at that point? There’s a wonderful moment in the game that visualizes this concept: Eliza’s portrait seems to suck in a number of default human 3D models, as if she’s breathing them in, all clashing into each other, faces blurred into a single multi-headed mosaic (see header image). It’s a monstrosity that masks Eliza entirely, her appearance, and her identity. It’s also a reflection of us, how we hide behind false portraits, the screen momentarily becoming a mirror of our own convoluted selves.

You can play Eliza in your browser.