Alex Harvey’s genre-bending, game-destroying take on Burroughs

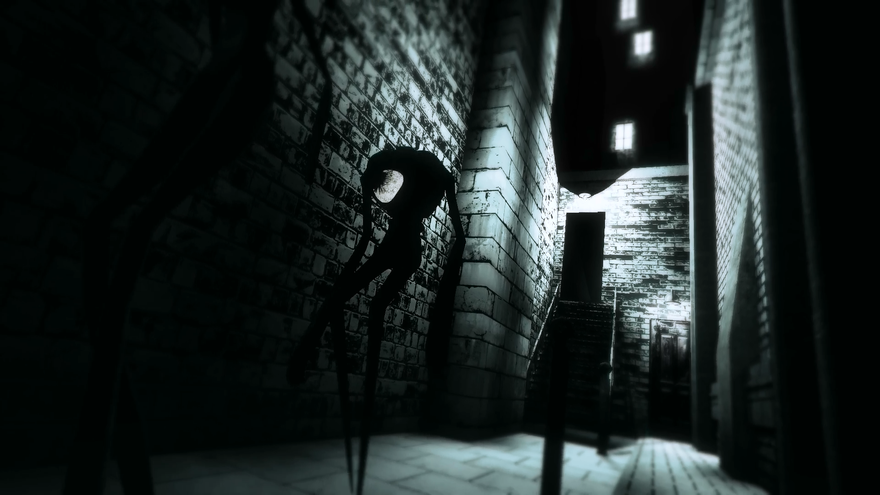

Header illustration by Jordan Rosenberg

///

A few summers back I read William S. Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, Junkie, and Queer back to back (to back). The overwhelming darkness and chaos of the writing ran together in my mind to become something almost physically heavy, coloring the period with a sense of foreboding and unease. That sounds like it would be a terrible experience, but it wasn’t. Instead, it was an impressive introduction to the work of an author who was incredibly talented at using his words to impart a sense of mood and place—to not just communicate stories that represent his view of the world, but to make them come alive in his audience’s mind through a disregard for structural convention and an embrace of forceful, messy, and raw emotional transmission. Reading Burroughs is an act of sharing headspace with the author. It’s uncomfortable because it’s frightening and confusing and sometimes downright nauseating in there. But, like much great art, doing so is a worthwhile process of slipping into the thoughts of a complete stranger and coming to understand some larger part of them.

A “love-letter to the darker avant-garde of the 20th century.”

Knowing that a game called Tangiers was coming out—a game by a developer who straight-up drops Burroughs’ name in describing their project—was as interesting to me as it was worrying. Even a director like David Cronenberg, who has built a career on the ability to translate the surrealism of dream logic to screen, had to take a roundabout approach to adapting Naked Lunch, mixing personal biography with fiction to turn Burroughs’ seminal work into something discernible. A videogame inspired by Burroughs and named after Tangiers—a Moroccan city that conjures associations with the author’s highly productive, opioid and cannabis-fuelled exile from America—wouldn’t work if it was only focused on the surface trappings of heroin, paranoia, and Eastern exoticism. But, once Tangiers developer Andalusian released a handful of screenshots, a brief trailer, and written explanation of their intent, it became clear that they were working with the material on a more instinctual level.

Tangiers’ website describes the game as a “love-letter to the darker avant-garde of the 20th century,” a “tense stealth game set within the confines of a dark, self-destructive world,” and a work “built in the shadow of Burroughs, Ballard, Dada, [and] Early Industrial.” Even though there is evidence of a deep reverence for Burroughs’ work (again, that name), Andalusian is wise enough to incorporate artistic influences within the writer’s orbit, rather than appropriate the specifics of his fiction. There are winks to Burroughs’ Exterminator!—the game’s protagonist, while often hidden too deeply in shadows to become clearly visible, resembles a distorted cockroach—but Tangiers feels like the product of an influenced vision, not one slavishly devoted to precise homage. Many of the gameplay systems are inspired by the worldview and creative process of the artists referenced by Andalusian, something that positions the studio as a modern incarnation of a tradition rather than a shallow imitator. Tangiers’ game world itself breaks itself apart, pieces of the environment re-appearing in other areas; the player can steal words spoken by enemy guards, visualized as actual text, in order to re-arrange their meaning and alter character behavior. These are systems designed by a developer that has obviously thought long about how their influences created art. They’re examples of design work that has studied and internalized creative processes, only to reinterpret them for a new medium.

///

Alex Harvey first became interested in William S. Burroughs due to the “dodgy VHS copy of Naked Lunch,” bought by his father, which seemed to be “floating about the house constantly” during his childhood. After Harvey’s slightly older brother secretly watched the film, he told his five-year-old sibling to never make the same mistake he did—that Cronenberg’s take on Burroughs’ novel contained “the worst, most horrible things to ever appear in a film.”

“So, naturally,” Harvey says, “a desire to one day watch [it] became embedded in me.” It wasn’t until Harvey was a teenager that he would find his way back to Burroughs. “I was really into the old industrial music—bands like Throbbing Gristle, Cabaret, and Voltaire—[and] that turned into a fairly obsessive desire to read more [and] learn more about their connections and influences.” Eventually Harvey would discover what he calls “a big family tree” of artists, which sprouts from the Dada movement and branches out to include Burroughs, J.G. Ballard, and David Cronenberg. The aesthetic of these artists, Burroughs in particular, was “as you’d expect, [like] catnip for an angsty teenager.”

This group of writers, filmmakers, and visual artists resounded with Harvey well past his teenage years. Beyond the cynicism and bleakness that outwardly defines their work, he found himself struck by the raw, “violent nature of their expression.”

“[The] work is often driven by its texture; by primitive emotive qualities rather than through more bourgeois, academic constructs,” he explains. “With Burroughs, through his cut-up [writing technique], you’ve often got borderline nonsense, but the impact comes from the beat and prose rather than through explicit, constant motif.” Harvey also found himself fascinated by the manner in which his “family tree” offers social commentary—a tendency best exemplified in J.G. Ballard’s doom-laden portraits of 20th century England. By refusing to observe society from a distance, choosing instead to wade into the muck of human interaction by focusing on the intimate details of how it breaks down, these artists make vital statements about how our behavior is “driven and tied up with environment, consumption, and industry” without these observations feeling like they’re coming from an aloof, distant commentator.

He found himself struck by the raw, “violent nature of their expression.”

Harvey is now Andalusian’s Project Lead, Art Director, and Programmer. The 25-year-old lives in Bristol, U.K. and taught himself game design after previously having devoted himself to independently studying film. At the same time as he was learning film analysis and design, Harvey worked in retail management (“running shifts and the like in supermarkets”) longer than he meant to while still dreaming of a transition into a career in game development. “[It] was around the time that I got laid off that [development engine] Unity had hit a suitable degree of maturity,” Harvey says. “So, I put what savings and resources I had into intensively learning anything and everything I could. Then, when [I was] ready, I started on Tangiers proper.”

Rather than approach game development through the traditional route of technical education, Harvey arrived via a background in film. This is clear in what has been shown of Tangiers to date. The game’s environments are primarily composed of moodily rendered industrial city streets, dense with pitch-black shadows contrasted with splashes of stark white light. Still images from Tangiers are skewed to an unnatural angle in order to highlight the already discomforting visuals and strange character design. “If someone describes something as a ‘cinematic game,’ what do they mean?” Harvey asks. “They don’t mean a game that understands and applies the nature of film theory. They mean a game that makes a clunky, slightly shite appropriation of cinema, stapled on to a by-the-numbers structure.”

Watching one of Tangiers’ trailers is something refreshingly distinct from videogames’ usual appropriation of film. Andalusian smoothly transitions from wide pans of the game’s vast, wheat-covered fields to faster cuts of its claustrophobic city streets as the understated mechanical groans of the accompanying music begins to develop a propulsive beat. It’s a video constructed with an understanding of how best to use the conventions of film to present a videogame.

While Harvey admits that his unique background means that “if I was told to make something finely balanced and very structured, I’d make a right ham of it,” there is worth in a videogame developed by those with a different perspective on the medium. “Any uniqueness or inherent value in Tangiers will come, partly, from being an outsider, but [also from] coming to game design with a literature/film background,” Harvey says. “It’s not a game made by people who grew up on Mario, [then] graduated to Final Fantasy and anime. It’s made by those of us whose idea of creative structure and practice comes from objects that are far, far less common an influence in the medium.”

///

Andalusian is currently made up of five members, but Tangiers began with Harvey working alone on a project intended to be “an utterly disposable game” he could use to introduce himself as a creator. With the addition of assistant developer Michael Wright a core team was formed, and the development process took on, as Harvey says, “the traditional two friends working out of a bedroom” stereotype. But around the time of a successful Kickstarter campaign (which raised £42,006, passing its £35,000 goal), the pair found their work hindered by the limitations of creating as a duo and began reaching out to mutual friends to find potential colleagues who could help develop Tangiers. The resulting list of team members is unorthodox, comprised of a varied collection of artists hailing from England, Spain, and the United States. “Only one of us has formal involvement in the [videogame] industry,” says Harvey. “All of us are pretty diverse in who we are and where we’ve come from. The last thing I wanted was a team where we’re constantly just agreeing with each other, coming up with the same ideas, and patting each other on the back.”

What Andalusian does share is a unity of vision—a desire to forge a studio identity built on “immersive sim-type, emergent projects [that] marry accessibility with strong creative [and] artistic aspirations.” Harvey says that the starting point for the team was to create in the tradition of not just Burroughs, Ballard, and the Dadaists, but game developers Looking Glass Studios (Thief) and Ice Pick Lodge (Pathologic) as well. In the future Andalusian wants to move on from the open recognition of its influences that is so central to Tangiers. Once the studio has provided players with an understanding of the artistic tradition it’s working from—“a pretty explicit introduction to who we are [and] what we’re about”—it hopes to “turn down the volume in later games” by focusing further on the elements that define it as a studio without so openly referencing specific artists. Harvey says Andalusian already has a few concepts in mind that focus on experimenting with multiplayer open-world experiences where “emergent A.I. personalities” inhabit procedurally generated, unending cities. He mentions Ballard’s The Concentration City as a point of thematic comparison.

Before that, though, he wants to concentrate on expressing the studio’s vision with Tangiers, a game that hopes to convey the same direct, unvarnished emotional and social commentary as the group of artists Andalusian draws influence from. When asked whether or not it’s possible for games—a medium consisting so wholly of logical structures—to accomplish this, Harvey acknowledges the challenge and the fact that his team has “had to rework a fair few things on Tangiers” in resisting the pull of an overly rules-based, staid-feeling gameplay experience. “Once we’ve established the expected limits [of a game], that should be the end of rule and structure,” he says. “Create something entirely holistic, where the world feels natural and organic rather than a series of gameplay hooks. The designer should absolutely apply themselves, but then erase all evidence of their presence.”

Tangiers, too, should allow players access to the minds of its creators.

Whereas the Dadaists used collage and Burroughs the cut-up technique—a process involving the random rearrangement of sections of writing—to purposefully abstract conventional artistic structures and hit the “true” meaning of a work, applying the same approach to videogames is more difficult. Harvey personally believes “the inherence of structure [in games] is a bit of a vestigial organ”—something that modern game design is growing out of as it moves further away from its purely systems-driven roots. “The mechanics of gameplay, as they exist in the form of structured action/reaction—they are the definitive, most explicit form of a facade,” Harvey explains. “They stand up and shout ‘this is fake!’ There is nothing authentic about them. They need to be buried.”

What Harvey and Andalusian want to do instead is create an intimate dialogue with audiences—one that offers something resembling a back and forth conversation enabled through player choice and emergent gameplay. Just as reading Burroughs acts as an intense transmission of ideas and emotion between reader and author, Tangiers, too, should allow players access to the minds of its creators. Or, as Alex Harvey puts it: “Using the game as the means of communication, let’s talk our fears and fancies; our anxiety and life experiences; our observation and sense of humour.”