On January 21, 2015, the day after Barack Obama delivered his latest State of the Union Address, The Guardian translated the speech into emoji. Phrases like “A brighter future is ours to write” were rendered using emoji suns, crystal balls, and notepads. Helpful translations were provided on The Guardian’s website, but the exercise suggested that emoji could replace words as a language in their own right.

If a tree falls in the forest and no emoji can express that reality, does it make a sound? A useful language must be able to convey a full range of experiences in a manner that its speakers can readily understand. Realities that cannot be expressed using a language come to feel less real. Sure, they happened, but what does that really mean? In that manner, a language’s blind spots can erase certain experiences.

The emoji familial unit was once a digital Norman Rockwell painting.

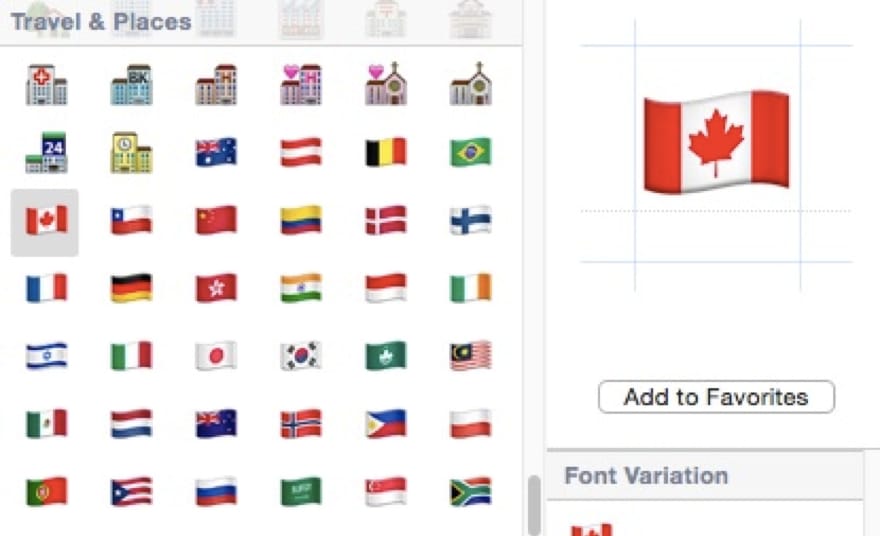

Apple released the latest version of OS X 10.10.3 beta and iOS 8.3 beta on Monday. These work-in-progress operating systems give the public a first look at, among other things, a future in which emoji are a diverse range of characters. Faces, for instance, can be rendered in a range of skin tones. The emoji familial unit, once the digital world’s version of a Norman Rockwell painting, now reflects the increasingly common inclination to marry whomever one loves. The new operating systems also include an Apple Watch emoji, because no good news can be separated from commercial realities.

General emoji standards are set by the Unicode Consortium, which is composed of representatives from major hardware and software companies. In 2014, the Unicode Consortium announced that Unicode 8.0, scheduled to launch in June 2015, would include a more diverse set of emoji characters. In a draft report edited by Google’s Mark Davis and Apple’s Peter Edberg, the consortium wrote: “People all over the world want to have emoji that reflect more human diversity, especially for skin tone.” The report goes on to introduce skin tone modifiers for emoji, a feature also included in the beta versions of Apple’s new operating systems. Many of the features Apple is previewing will be coming to other devices.

Recent cultural debates have highlighted a lack of diversity in a number of narrative forms. Excluded groups rightly want to be able to see themselves—and be seen—as fully rounded characters. This is not navel-gazing; it is an unfortunately necessary assertion of humanity. But how can one’s humanity be conveyed in a language that does not have the capacity to express certain groups’ existence? In that respect, the current lack of emoji diversity is a deeper problem than the lack of diverse stories. Even if one wanted to tell stories about minority experiences, the necessary linguistic tools do not exist. That will soon change, and not a moment too soon.

In international law, the de facto standard for nationhood argues that an entity only becomes a nation when it is widely recognized as such. The upcoming Unicode emoji standard offers a sort of national recognition. It operates under the principle that flags should “be present for all of the valid country codes.” (One can imagine a future in which territories campaigning for nationhood seek recognition from the likes of the Unicode Consortium instead of United Nations membership.) Unlike nationhood, personhood should never be dependent on the recognition of others, but it often feels as if it does. Thus, the Unicode Consortium and Apple’s affirmation that the experiences of all people—irrespective of ethnicity or sexual orientation—deserve to be fully expressed shouldn’t feel like a radical proposition, but it does.

Images via Macrumors