It’s usually clear where a novel or film begins and ends. But what about a game? Today, games exist at all lengths. They can be five-minute narratives, hundred-hour undertakings, or even potentially endless preoccupations. How do we know when we’re done with a game, or when we’ve actually started? Below, Kill Screen founder Jamin Warren and staff writer Michael Thomsen debate the act of reviewing, understanding, and “finishing” games.

Michael Thomsen: So far I’ve written about two games I couldn’t finish before deadline. The first was Final Fantasy XIII. I reached the penultimate chapter after two weeks of play. My editor’s patience was at an end and I realized I had lost all understanding of who my characters were and what was happening in the story, and so decided to cave to the pressure and start writing. The other was Monster Hunter Tri, which I played for about 30 hours and realized I was less than half of the way through the game, and so I decided to instead write about the time-vertigo of playing such a long game—which strikes me as an interesting contrast to the heretical story I wrote about Dark Souls, a foul and stupid game that I forced myself to finish in spite of how unpleasant it was to play.

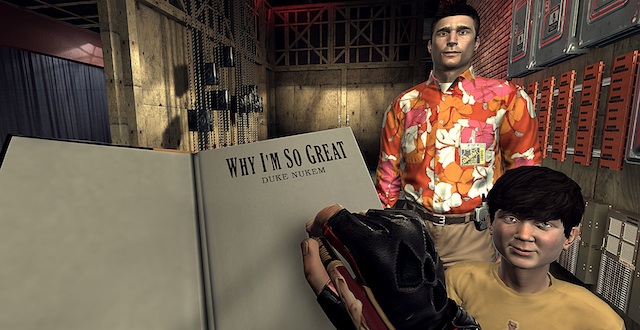

I like both the Tri and XIII articles, but they’re also wispy and searching. They seem to be out in the ether looking for a hard border to crash up against. I had that same sense reading your review of Duke Nukem Forever, a game that was, like Dark Souls, intensely unpleasant to play. I also wrote about it, and forced myself to play all the way to the end. I found the basis on which you were judging incomplete. It was a review of a hype cycle and the cultural delusions of teenagers, neither of which speak to the game itself. In a review, the subject should be the game as object, not the game as cultural circus, nor the game as a reflection of the writers growing bored with it.

Jamin Warren: I don’t think that you have to finish games to review them. Obviously, there are games that do not have an end, such as Tetris or Drop7; but I think those games, like massively multiplayer online games, raise a different question—which is how long one needs to play them to feel they can adequately create and relay an opinion to the public about them.

Even with some story-based games—such as the recent Uncharted: Golden Abyss for PlayStation Vita, which was abysmal—you can form a pretty good opinion about what the game is supposed to be, 95 percent of the time, even if you only make it halfway through. There are very few games where the ending actually matters. Unless there’s some magical thing that happens, like BioShock or maybe Heavy Rain, where the ending is crucial.

Maybe some of it comes from my background as a cultural-studies person. I am much less interested in the production as I am in the reception. You’re right that I was reviewing a hype cycle with Duke Nukem Forever, reviewing a history of juvenilia and adolescence. I think reviews should take the reader into a particular reviewer’s perception, or the world they’re inhabiting, when they’re playing and critiquing a game. I don’t think that’s necessarily tied to this idea of completion. Sometimes the most interesting thing is what happens in the first 10 minutes of the game, as opposed to hour 17.

Mike: Let me propose a little bit of heresy to this binary distinction between story games and what I call cyclical games. Chess recurs in cycles; it’s got a discrete, round-based structure to it. You play Drop7 until you die, and there is no end stage. Those sorts of games—like Tetris, or chess, or Drop7, or Primrose—those are games that to me should not be reviewed. They’re games that fundamentally cannot be reviewed, because they are so completely dependent on the people playing them that they can be bent to almost any sort of experience. There’s no coherent way to review chess. Chess is just sort of a thing that you explore endlessly, a problem generator; and the sorts of problems that you create within it are reflections of the person interacting with it.

I think those are separate from what the majority of videogames are. In most cases, videogames do have a conclusion. Super Mario Bros., or Kid Icarus, or Halo, or even World of Warcraft has a distinct endpoint, and I think the only coherent things worth reviewing are things that are designed with an explicit endpoint.

What I take a review to be is an exegetic deconstruction of how much value a system or a videogame has. With Duke Nukem, it’s not that it’s not interesting to write an account of your disengagement with a thing. I think you can only write that story once, because that story is always the same, even though there are a million different variations. All this tends to be about the person playing more than the object.

I compare it to taking an assignment to climb Mount Everest. Nobody wants to read about me getting to the base camp. There’s Into Thin Air; there’s a long history of people writing very well about failure. But if you take the game as Everest, the review should be an account of getting to the top of Everest. What did it cost you; was it an easy hike not in terms of difficulty, but in terms of your own creative endurance? How quickly were you bored with it; how quickly did it become rote and repetitive; how much of a surprise was there in the ending; how much meaning came out of the boredom? I don’t want to just have peeked into the closet door and seen an undulating pile of nightmare slime in there, and shut the door again. I want to go in there and examine in close detail the whole awful specter of what I’m experiencing.

There are a lot of games that use cyclical boredom as a thematic element. Dark Souls is consciously drawing you through these extraordinarily tedious stretches and just challenging your patience for thematic effect. And it has a really clever ending; the self-loathing inherent in its masochism is really sharpened by knowing that its final gift to you is a release borne out of death. The same with Duke Nukem—there are a lot of repeated ideas and poetic mirrors with the original game, and there’s still a vibrancy, a mania to them that holds a happy aesthetic mirror to the awkwardness and overeagerness and tawdriness of being a teenager.

To me, that’s a model of what comes out of playing a game to its conclusion—it forces you to get past your own instinctual reaction to it, and to really begin to examine why you’re reacting to it in that way. Not just through being introspective, or thinking on your own, but through thinking while you continue to play the game, and having those sorts of thoughts as a dialogue with the game that you’re already irritated with. Rather than disengaging with the game, and then going to your laptop and sitting for a few hours and thinking about that brief snippet with the game and why you didn’t like it, you express your frustration with the game within the language it’s provided for you to express whatever you can express.

Jamin: I haven’t played Dark Souls, but the idea that I finished the game, and now I’m able to explain these large stretches of tedium—that’s such an outlier. The fact that it achieved that is certainly wonderful; but that is the exception to the rule, in that most of the time, for terrible games, that tedium yields no benefit. Super Meat Boy uses extreme difficulty as a design principle—as a fetishized value that yields its own rewards because you’ve persevered, and that’s a way to justify said perseverance. But we can critique difficulty as not being something that we should value.

There is this elephant in the room for me, which is just time. I’ve been reading Anna Anthropy’s book Rise of the Videogame Zinesters, and one of the points she makes is that games for the last 30 years have been designed by, more or less, either adult males with adolescent dispositions, or by actual adolescents for other adolescents. That’s created a value chain particularly around time that frankly merits critique.

I was talking to someone at another game website that takes the preview/review embargo cycle way more seriously than we do. He was saying that you have a two-day window when the first set of reviews come out, and if you don’t get in that window, you’re fucked. There are simple realities of finishing a 40- to 60-hour game. I want to leave a possibility space open where you can justifiably not finish something, and still write something of worth.

Mike: Most games that writers are asked to review are just not worth reviewing, just as culture. If you don’t care enough to finish the game, you probably don’t care enough to write about it.

The time constraint thing, I think, is overblown in most cases. As someone who started reviewing books a fair amount in the last couple years, I find there’s huge crossover with the constraints one has in reviewing a book with the constraints you have in reviewing a videogame. I wrote about the Neal Stephenson book that came out last year, which is 1,000 pages, give or take: this massive, awful, hulking beast of a book. Very often you have a very short turnaround period for books also. There are famous stories about the Walter Isaacson biography of Steve Jobs, where people had three days to turn around a review, or sometimes even less. And they just sort of trained through 300 pages of reading and wrote a couple thousand words to make deadlines so that they would have reviews for the day it came out. I don’t think games are so unique, then, in that sort of time constraint.

Jamin: Games value length; it is a thing that is advertised. The average book is two to 300 pages, maybe 400. That is maybe a five- to six-hour commitment, tops. I don’t know how long I spent with that Uncharted game on Vita, but it must have been nine to 10 hours, most of which were entirely unenjoyable. The Isaacson book, or Murakami’s 1Q84 that I’m reading, which is 600 pages—those are unusual.

Mike: I read about 20 pages an hour; maybe that’s just hyper-slow, but a 300-page book to me is a 1,500-hour investment—especially reviewing it, and taking notes for quoting later on, and keeping track of things. I don’t find there’s a dramatic difference in time investment for me.

Jamin: We’ve been talking about finishing and not finishing games as this on/off switch. There’s also a gray area. I ran into this with my Journey piece because I played it offline. The big critique was that I played and there were no additional journeyers with me. The worry I have—and this is true with very difficult games—the rhetoric is, the game doesn’t really come to life until hour seven or eight, or until you’re a level 30 black mage. I’m tempted to believe folks who say that, once you’ve overcome the initial 40-hour difficulty curve, the game is awesome. Fighting games are like that: the game doesn’t really come to life until you’ve mastered that single character. But for me that highlights the inherent futility of the traditional way of reviewing games as software, where we check off a list of features; and is why I feel you could only deal with games as a personal experience or narrative. Which I know you don’t like, because then it’s about you and it’s not about the object itself. [laughs]

Mike: The irony of my position is that you can never not write about you. I don’t want to argue for an austere, depersonalized, objective approach to games. At the same time, if you have counterarguments or moments of distaste, there are a lot of ways to express that or experiment within the game. Games like Fallout, which are designed around flexibility and response to player input; if you’re getting pissed off that it keeps making you fight everything—one of the remarkable moments in Fallout 3 is where a guy keeps shooting at you, and shooting at you, and shooting at you. I realized that you can actually shoot the gun out of his hand. There’s no way to talk to him and pacify him. But if your aiming is high enough, you can actually shoot the gun out of his hand and that immediately makes him peaceful. That changes the whole way the game played for me. That’s an example of expressing my distaste for something in the game through its systems, and using it to test what else it can do, besides the things that irritate me.

Are these irritations a product of my own narrow imagination or narrow expectations of the game, or is the game actually more flexible than I’m giving it credit for, based on my presumptions? I think every game deserves to be heard out to its completion, not just as a process of passive receiving of the system that’s been designed for you, but a testing of the system based on your own reactions to it. The more of a dialogue it becomes with your reactions to it, the more meaningful the review is. I wound up pretty disgusted with Dark Souls, really turned off by the insistence that you go so far with it, and it gives you so little in return for having given so much to it.

There’s still a smell of bullshit to almost every videogame story I read, even as it’s advanced to a very high level being in The New Yorker and The New York Times Magazine. To me it derives from this politeness about the thing that’s experienced. In literary criticism there are really cutting deconstructions of things that are inadequate—Nabokov talking about what a fraud and charlatan Faulkner was—but there’s this really intelligent, but painfully milquetoast, quality to the way we appreciate games. It’s a reflection of how partially engaged we are with each one. We consider games primarily as ideas, rather than actual evolving relationships that we’ve had over time. There’s the concept of Dark Souls, which is a really poetic, ambitious thematically broad statement about masochism and hopelessness and despair and how much pain and suffering you can endure. But then that begins to fall apart as you actually go through the experience. I think it’s important to balance the idea of the game against the actual experience of the game: you criticize it.

I just played Journey the other night, too, and I had a mostly negative experience of that game. My reaction hewed pretty closely toward yours—it was a miserable thing to play and I wanted it to be over almost the whole time. Half an hour in, I get it: Life’s a cycle, it is what you make of it, and you can never make as much of it as you want, and sometimes people help you and there’s this limited but very meaningful support and intimacy that comes out of that; but it can never go beyond this animalistic basic-ness of just being in company with another person. And then you die and it starts all over again. That was 20 minutes in; it’s in the second room. I’m glad I played it all the way through, but I think I could have written as meaningfully about the game with half an hour of experience of it. Which is probably why I haven’t been interested in writing about it. But anyway, now I’ve refuted my whole position. [laughs]

Jamin: I want to allow the writer the ability to do that. It made sense for me not to finish Duke Nukem Forever. The point is, the cultural context for that game was so overwhelming that it does not matter at some level whether it was a good game or not.

Image via Crossett Library