The 39 Steps—based on the 1915 John Buchan novel of the same name—is a lovingly rendered atmospheric spy thriller set on the eve of the first world war. Richard Hannay–a Scotsman who has lived most of his life in colonial South Africa, where he worked as a mining engineer and fought in two or three wars–finds himself middle-aged, wealthy, and adrift in London. His ennui–which bears more than a passing resemblance to Charles Marlow’s in Joseph Conrad’s 1899 novella Heart of Darkness–is broken by the sudden appearance of a man named Scudder, who claims to have knowledge of an anarchist plot to assassinate the Greek Premier and thereby foment a pan-European conflict, and to be a marked man himself on account of the anarchists knowing that he knows their plans. Hannay, glad to have something to fill his days with, gives Scudder safe haven and takes up his cause; soon enough, Hannay’s the one on the run from both the anarchists and the law.

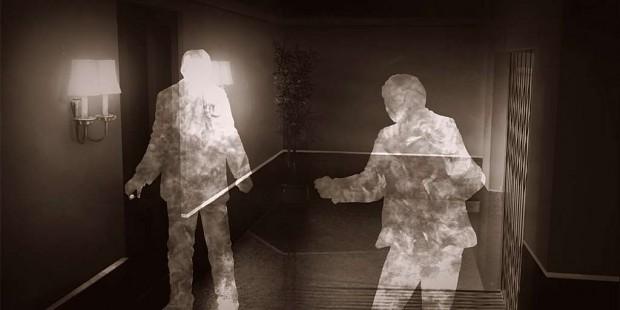

The narration is a mixture of on-screen text and voice-over, competently acted. Human figures are rendered as frozen vaporous silhouettes in the scenes, a design efficiency that advantageously amplifies the air of conspiracy on which the story relies: even when you’re looking at these men and listening to them, they’re barely more than brightened shadows.

The 39 Steps should appeal to anyone who appreciates a good mystery or graphic novel (there are five film adaptations of varying degrees of faithfulness to the original plot, including one by Alfred Hitchcock) but is crippled by a complete failure to match what you’re doing in the game and how you’re supposed to feel.

In an early stage (chapter, perhaps?) set at a private club where Hannay hangs out, I read the first page of a newspaper and the first page of a book. I looked at Hannay’s leather wallet, which had an inscription honoring his colonial service. I knew what to look at because the touchable elements in the otherwise still screen (think the original Myst) shined as if lit from within.

Upon first firing up the game I had assumed that I would be playing as Richard Hannay, but instead, Hannay was introduced to me by way of a black screen on which were listed a half-dozen subject-headings about his childhood, colonial service, etc. Clicking on any one of these yielded up a few sentences of narrative from the novel, accompanied by what seemed to be a historical photograph. The entry for “The Soldier”, for example, read “I served the British forces during the Matabele conflict and was decorated for my role. I served two years with the Imperial Light Horse and was an intelligence officer at Delagoa Bay in the second Boer War. I lot many friends during those wars.” Next to this was a black and white photograph of a group of men posing before a nondescript building made of corrugated tin. They aren’t identified and you can’t enlarge the image. It reminded me of using Microsoft Encarta in the early 90s.

The first time through I read them all before clicking “done”, at which point I was notified that I had “collected” Hannay. This meant nothing for the game play itself, but when I exited the main story, went to a menu on the home screen marked “extras” and from that menu chose another marked “cards”, I found a “card” with a drawing of Hannay on the front and a thumbnail description of him (a further abridgment of the biographical summaries encountered earlier) on the back. Well, okay.

A second run-through of the scene revealed that I could skip Hannay’s whole biography and still “collect” him, though I was denied that chapter’s “award” for thoroughness, which is given only to those who click every possible clickable thing in a given section.

Anyway. After leaving the club, Hannay went home. A still image of a residential building on a London street appeared. A diamond icon floated in the doorway of the building. I made him go inside. Upstairs, I was prompted to trace a short sequence of straight and curved lines on the screen of the iPad to simulate the motion of his opening his front door. “The finger thing”—as I came to think of this demeaning exercise fit to teach coordination to a preschool-age child—is the most unfortunate recurring feature in 39 Steps.

I was forced to do the finger thing to make Richard open doors, eat dinner, and even, at one point, trim his mustache. There was little logic to the activities chosen for this mechanic, and no representational relationship between the player’s act of tracing and whatever Hannay was doing that it was supposed to symbolize. It was the closest that 39 Steps ever got to offering a challenge, but in the end the only thing tested was my dignity.

It wasn’t the crudeness that bugged me, it was the pointlessness of the interactive elements being included in the first place. Being prompted to click on the only clickable thing in a given scene doesn’t make you feel like a participant, much less a player. It makes you feel like you’re watching a cinematic cut-scene in an old-school RPG—your instinct is to click through as swiftly as possible, hopefully absorbing the story and any clues, but mostly focused on getting back to the action. But in this case the cut-scene is the entire game.

Playing 39 Steps is like watching a movie that pauses itself every fifteen seconds to ask you whether you’d like it to keep going. The intrusions are as annoying as the hiccups and they undermine the best of what the game has to offer: fine visual detail work, the moody accrual of paranoia, and any sense of the thrill of the chase—which last is truly unforgivable for an adaptation of the book that practically invented the modern “man on the run” narrative.

The estimated playing time is five to eight hours, but I completed the game—including “collecting” all but one of the twenty-five cards, and all but three of the nineteen “awards”-—in about three hours. This, I couldn’t help but note, would have been just enough time to watch the Hitchcock movie twice.