Exhuming Grim Fandango’s Mexican folklore inspirations

Grim Fandango is a game about exploring the unknown, some of the deepest mysteries of life, as seen through the lens of Mexican folklore and film noir in a point-and-click adventure. Even all these years later, that sounds like an incredibly odd and ambitious combination for a videogame to express. Not that larger or mid-tier games haven’t displayed creativity on that level since 1998 when Grim was first released, but its implied abject lesson is that this particular cocktail was spiked: When people talk about Grim, they also talk about the “death” of the adventure-game genre in the late ‘90s. They’re saying it was “ahead of its time” and “too creative.” Anything else that goes this far over the line will mean trouble—for its creators or investors.

All of which may have been and continue to be true, but it’s also possible the game and its intentions were never fully understood or appreciated. In all those years of it being inaccessible, curious players were more fixated on asking: How can I play find and play it? With that soon to no longer be an issue, another question arises: What the hell was this game and how did it come together, anyway?

More specifically, what does Grim mean when it purports to be “inspired by Mexican folklore” and film noir—two very broad categories in and of themselves?

“I would suppose when I just hear [that phrase] and don’t see the game yet that means they have researched popular beliefs and spirituality and religion and popular culture in Mexico,” says Dr. Tey Marianna Nunn, the director and chief curator of the Art Museum and Visual Arts Program at the National Hispanic Cultural Center in Albuquerque, N.M. “Often when people use the term ‘folk’ they’re talking about going all the way back to pre-Columbian: general popular beliefs, thoughts, art, etc.”

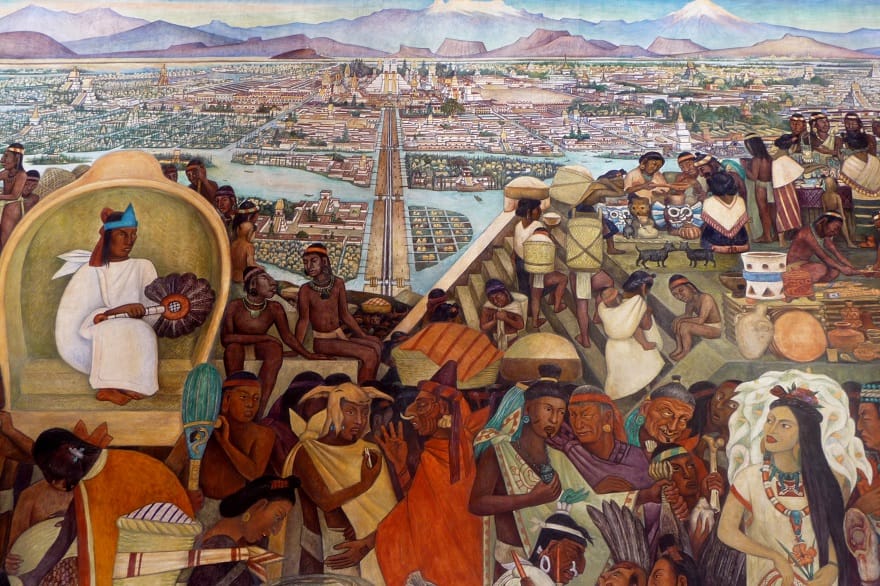

What pre-Columbian refers to here are the Aztecs, whose influence on Grim is strongly pronounced and clearly evident. As the aforementioned travel agent, Manny Calavera, your job in the beginning of the game is to get newly dead the best possible packages to the Ninth Underworld—their final destination. In Grim, those who did good deeds in the Land of the Living earned themselves a ticket on the Number Nine, a train that will take them to the Ninth Underworld in a speedy four minutes. If you were less than saintly, you have a four-year hike ahead of you—but on the plus side you get a walking stick with a compass in its handle.

This is all a creative re-imagining and interpretation of the journey to Mictlán, which is in the ninth level of the underworld. Getting there is a grueling four-year journey where the dead must slog below the terrestrial level. Yes, beneath that, according to Professor Manuel Aguilar-Moreno’s Handbook of Life in the Aztec World, there are nine levels to the underworld—realms that the souls of the dead had to cross. They are:

the place for crossing the water, the place where the hills are found, the obsidian mountain, the place of the obsidian wind, the place where banners are raised, the place where people are pierced with arrows, the place where people’s hearts are devoured, the obsidian place of the dead, and finally, the place where smoke has not outlet.

Like other aspects of Aztec and Hispanic beliefs, Grim has some of this in the four years its story is told.

Even in this one example, Grim demonstrates that it’s playing a little fast and loose. The notion that how you lived your life dictates how you’re treated in the afterlife has more Eurocentric roots than Aztec. According to Book 3 of the Florentine Codex, “one of the most important accounts of Aztec mortuary rites and beliefs concerning the hereafter… the treatment of the body and the destiny of the soul in the afterlife depended in large part on one’s social role and mode of death, in contrast to Western beliefs that personal behavior in life determines one’s afterlife.”

The Codex says Mictlán is for “people who eventually succumbed to illness and old age.” There’s also Tialocan, “a region of eternal spring, abundance, and wealth” meant for those who “died by lightning, drowning, or were afflicted by particular diseases or gout.” There’s also a side door for those who were buried alive.

In other words, the framework for Grim’s plot isn’t as clean-cut as it presents it: You spend most of the game chasing after a nun who was supposed to get a ticket on the Number Nine but ends up with a walking stick.

Getting it “right” is a bonus

To be clear, this game has talking skeletons walking around smoking cigarettes running casinos. Obviously, creative licenses were taken. A videogame’s purpose is often not: “Did it get it right?” Rather, it is: “Is it fun or interesting?” Getting it “right” is a bonus, a goal that should be respected mindfully.

But Grim never intended to be strictly adhering to any one aesthetic or inspiration. “I wouldn’t say Grim Fandango is all about that, though,” says Nunn. When you see a game as a finished product, be it in your Steam library or on a store shelf, there’s the temptation as a consumer to take it at face value as being very intentionally the sum of its parts. Not so with Grim, says Tim Schafer, the game’s writer and director.

“It [was not] really calculated,” says Schafer. “We definitely were trying to be authentic but it also just had a lot to do with the team. Mexican folklore is definitely important to it but if it had ended up on the desks of a different team, it probably would have been handled a lot different.”

Also, Schafer adds, Grim’s mixture of film noir and Mexican folklore has a very human explanation behind it: They just happened to be two things he was really into when it was time to plan his next game.

“I was really interested in film noir right when we were also kind of mulling around the right way to do a Day of the Dead game and it was—a lot of times you have ideas floating in your head for years and then two of them will crash into each other and you’ll realize that they accentuate each other,” says Schafer. “That’s what happened with Grim.”

As for the creative liberties that were taken in mashing up these two disparate inspirations, Nunn says “they were really paying attention” in deploying Mexican aesthetics—particularly when it comes to the game’s architecture. When I checked out a demo of the remaster at IndieCade last year, Grim’s commentary track has Schafer talking about how 450 Sutter St. in San Francisco was an inspiration. This is something he’s written about before (it’s his doctor’s office), so not exactly a revelation, but an indication that they did their homework—the building is “San Francisco’s monument to the Mayan Revival branch of Art Deco.”

“One of my superpowers is to be able to go, ‘Oh, I think there was a Latino set designer involved in this,’ or ‘I think somebody really did their research or somebody really didn’t do their research,” says Nunn. “I think this game sort of borders both.”

When asked what other correlates there might be in film or TV that gets the same amount of things “right or wrong” in drawing inspiration from Latino culture, Nunn—after much consideration—says Fools Rush In, Nacho Libre, and maybe El Machete are the best examples.

“They set a precedent for at least the search for some authenticity regarding Latino culture,” says Nunn. “Latino culture is by no means homogenous and so all of these movies attempt to show the nuances, cultural exchange, blending, mixing, and blurring of borders. They do this all the time with wit, sarcasm, and a nod to Latino aesthetics and sensitivities.”

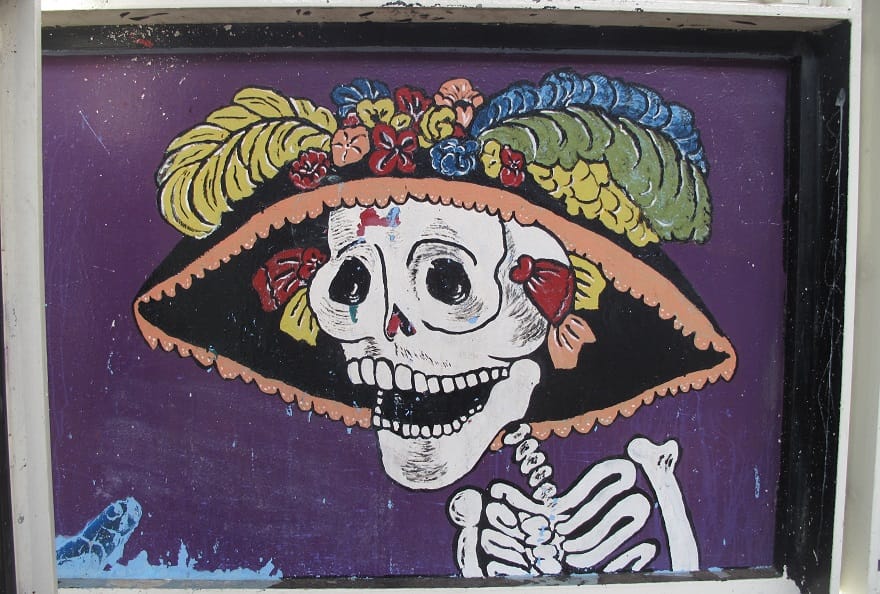

Unlike film noir, Schafer’s passion for Mexican folklore was not a passing fancy just in that particular time in his life. When Grim came out, it was the realization of his longtime fascination with Latin American folklore. As an undergrad at the University of California at Berkeley, Schafer first encountered Day of the Dead images in a class with folklorist Alan Dundes—things like the political cartoons of José Posada.

How can I venture into another culture’s folklore and use it for this game and feel good about that?

He recalls “falling in love” with Day of the Dead and its history, something that had “roots in a very serious religious festival that evolved into a civic town festival and then almost more of a tourist festival that was purposely amplified by the Mexican Board of Tourism to make it a little more festive.”

But Schafer’s fascination with Mexican culture dates back further. His mom was a secretary involved with the American Field Service, a student-exchange program. The Schafer household hosted students from Guatemala, Japan, Africa, and a few from Mexico. As a boy, he ran around Morelia, Mexico with other young kids, exploring, and unknowingly, taking it all in for later.

So, the creative deviations Schafer and his team made were not done lightly. Oftentimes, Schafer says, they were the result of trying to make a game like this in a pre-Internet time, limited to whatever libraries had on hand or could interlibrary loan. Reading about Mictlán, it just sounded like a quest. Whenever things were vague in Schafer’s research, he “just made up some things.”

“I was well aware of how it could come off as a really crass cultural appropriation,” says Schafer. “On the one hand, it’s great to have representation of different cultures in games. It would be nice if it was being made by a developer that actually came from that culture, but I couldn’t really change that. But I did feel like, ‘How can I venture into another culture’s folklore and use it for this game and feel good about that?’ My main answer was, ‘I’m going to try to be as authentic as possible. I’m gonna research this and I’m going to try to capture not just specific details and the words, but also the themes and feelings of it.’”

Even when Grim does stray from its source material, though, it finds ways of staying true. For example, a major obstacle in designing the game was imparting a sense of danger—you’re already dead, so what can really happen to you? True, in direct opposition to the Sierra adventure games of old, LucasArts games always avoided opportunities to kill you off.

“That actually came to be a difficulty with the story,” says Schafer. “You want people to be scared of the bad guy with the gun because they’re gonna shoot you. How do you do that in a situation when you’re dead already?”

That’s where “sprouting” came into play: “The idea that you get sent back to life, or turned into a bunch of flowers. It’s more of a cycle, back to the Land of the Living as a flower.”

“Sometimes in folk art you’ll see [regeneration or reincarnation] in folk art, but to my knowledge there aren’t folk tales or popular culture about that,” says Nunn.

What’s funny in all of this is Grim’s re-release is being made possible thanks to LucasArts being purchased by Disney, a company with an unexpected storied history of cultural insensitivity: In 2013, Disney tried to trademark the phrase “Day of the Dead” for a planned future and ostensibly since-canceled Pixar film.

As Schafer and his team proved with Grim, though, these types of missteps in creativity are not inevitable. They can be circumvented if you think about games as cultural artifacts that are a part of our lives just as much as their subject material. They have consequences and mean something to their audiences, and should be treated as such by player and creator alike.

“We did think about the risks of cultural appropriation and I think ultimately it’d be great if as far as the diversity of game development goes, there was a game about Mexican folklore that was made by someone from Mexico—and I’m sure there has been,” says Schafer. “But I feel like games are really cyclical. Games are made and they appeal to people for the most part who are similar to the people who made them and then those people get inspired to grow up and make games themselves. So you have a lot of same-isms, and just a lot of repeated cycles of people wanting to make what inspired them when they were younger. If that never expands, then games will always stay stuck in this kind of cycle. Maybe Grim wasn’t made by people who were of that culture but maybe it spoke to someone and by being on a new topic, something that wasn’t of a genre that was in games, would maybe reach new people and it could reach people outside of the currently identifying as gamers. That it would reach someone new, and that person might grow up to make games, and that would broaden that circle and help make it bigger and bigger.”

///

Header image from Dan Puplus

Image of Diego Rivera mural from Jen Wilton

Image of ‘La Calavera Catrina’ at 18th station mural from Duncan C