While in graduate school, cultural anthropologist Natasha Schüll developed an acute obsession with casinos. This is understandable. Casinos occupy a special space in pop culture; they exist at the nexus of consumerism, vice, and possibility. The bright lights, the sense of adventure, the alluring jingle of success. What’s not to love? They are, in a word, seductive.

But it was the small details that attracted her, the interior design in particular. The serpentine layouts, the dull carpeting, the perpetual state of magic hour. “It was actually a pretty bleak line into that world,” she says. One particular object, however, grabbed Schüll’s attention more than any other. It was the lowly slot machine.

While years of Bond-girl-blown dice and the emergence of big stakes poker on television may color the public’s perception of casino culture, it’s the slot machines that are true workhorses, accounting for more than 75% of revenues for many large casinos and an even higher cut for small ones. “Casinos are really about the machines,” she says.

Schüll’s new book Addiction by Design: Machine Gambling in Las Vegas outlines the shift from the social dynamics of gambling to something much more solitary. Slots lull players into a complicity known as the “machine zone”; the increasing mechanization of slots allows casinos to manipulate players on the fly, tracking their everyday behavior and adjusting their experience manually. Our stereotype of the old lady playing the one-armed bandit has been replaced by the all-consuming “time on device.”

In the past year, critics of social games have accused companies like Zynga and others of treating their players like lab-rats. Ian Bogost called them “the Wall Street hedge-fund guys of games” and while the recent figures for Zynga have been less flattering, that’s merely mistaking content for form. It’s not what games social game makers are creating, but how they’re pushing them out the public and changing user expectations along the way that’s notable — and troubling. Perhaps we should not be surprised that Zynga recently filed for a license with Nevada Gaming Control Board to become to online casino behemoth they have always appeared to be.

That’s where Schüll comes in. She sees the emergence of slot machines as part and parcel of a larger shift away from others and towards our screens. “Texting, phones and personal computer are the ways in which people are focusing on their own little screens,” she says. “It’s part of this intimate sphere of being ourselves in the world.” Slot machines are just a reflection of our own transition from creatures of the crowds to those sucked in by screens. This is not in itself a bad thing, but it has shifted the way that slot machine manufacturers and casinos regard the machines, the their users. As slot machine companies began to study how the customers interacted with their device, they adopted the famous Goldman Sachs adage of being “long-term greedy.”

Schüll points to a metric called “Time on Device play” as emblematic of the state of modern slots. In the past, the jackpots were a chief part of the allure. You would plop down with a bag of quarters and hope for the big time. If you lost, you walked. Slot machines were limited to a single line and you pull the “one-armed bandit again and again,” she says.

But then something happened — screens. No longer limited to a single row of lines in the analog days, a video screen could now show dozens of rows adjusting the way gamblers perceive their risk. Penny slots are becoming the most popular form of the game; you put in 100 cents , lose some, but gain 15 cents back. This creates a morphine-line drip to keep gamblers attached, literally tethered in some cases, and allows casinos to extract more revenue from their patrons. It’s actually called “Costco gaming.”

Then there’s the rise of player tracking. Many casinos give power users rewards cards that they load with their cash. This is touted as an easy way to avoid carrying cash and a way to earn perks, but casinos, of course, use them for behavioral analytics to determine what type of gambler you are. One of my favorite Radiolab episodes outlines the on-the-spot tweaking that pit bosses make at Harrah’s Casinos to keep players at the machines and happy with their stay. The candidness of the manipulation is both fascinating and frightening.

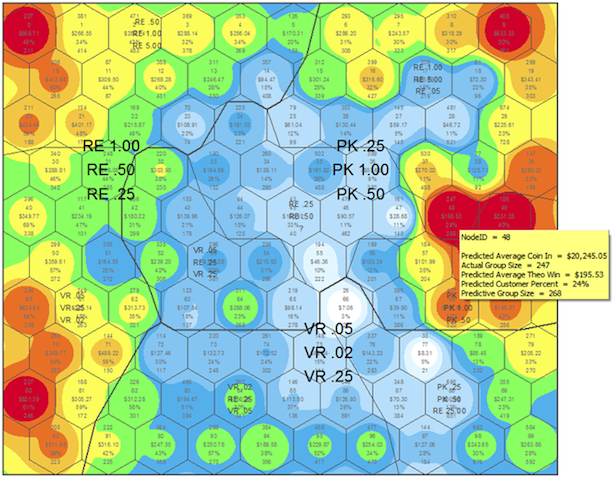

Tracking is very commonplace. According to Schüll, 82% of all players use these cards and are tracked according to how fast they spend their cash. Moreover, all this data is collected and compiled. “The cabinet you’re sitting in front of is no longer housing the game; it’s just a receiver for games that are on a server,” she says. “So if it’s Sunday at 11, the casino knows exactly what kind of player you are and what your risk profile is.” In an essay for Limn, Schüll explains:

As in the case of online venues like Amazon.com, individuals’ consumer behavior in casinos, recorded in a common data cloud and refracted through statistical analysis, becomes the basis for group classifications of which they may not be aware but in which they continue to participate—sometimes more robustly as a result of the customized product marketing that follows. The contours of touch-point collectives are honed through an iterative process of data differentiation and marketing response that tends toward a telescoping of group tastes.

So what does all this have to do with games? Well, the same techniques employed by slot machines map almost perfectly to developments in the world of games. The low price points of mobile titles keep us connected by incremental drips of one dollar at a time. “99 cents is the new quarter,” says Seamus Blackley, one of four founding members of the Xbox team and the head of mobile gaming startup Innovative Leisure. Now that price has naturally dropped to zero with the advent of freemium. There are, of course, benefits to lowering barriers of entry for new titles, but there costs as well. “The app stores are made to churn,” Machine Zone co-founder and CEO Gabriel Leydon said at a recent conference. “The OS providers want users to download new apps every day, so basically the App Store is your friend but also your worst enemy.”

Above: Natasha Schüll

For video game players, our daily interactions with screens often strike us as innocuous. They are things we play by ourselves (or perhaps with others), but we rarely stop to think about the process of design that goes into how games are actually made. Just as we watch games, games are watching us. Microsoft recently filed for patents to use the Kinect to observe those watching programs (ostensibly to charge more for social viewing events), and there’s no doubt that these devices will be use to adjust and learn. There is of course a bright spot — studying players ostensibly means better games. Data in itself is not a bad thing, but the worry, of course, is that the same comprehensive data profiles that casinos use to mark their patrons will become standard tack for game companies as well.

I asked Schüll what she thought of games. She’s not a big player, but the one thing that struck her about research was the question of time. There are, of course, ethical conundrums around privacy issues that appear in her research, but she was in some ways less concerned about the cost to the elderly consumer’s pension plan and more concerned about the sheer number of hours that slot machines were extracting. “People often ask me if the bad thing is that they take your money. I find the taking of time as just as disturbing,” she says. “That’s something amiss. We’re focusing they’re taking too much money. The monetizing. But it’s just as problematic if you look at time as a unit of value.”

One game designer told me that he saw no difference between a game like Skyrim that sought to be an all-encompassing, all-consuming and the same design end in many social games (or slot machines). Games have always been viewed as a waste of time by the public writ large. My worry is that game designers will prove the naysayers right.

Header image courtesty of LIMN Magazine