Glaciers writes poetry using Google’s most popular searches

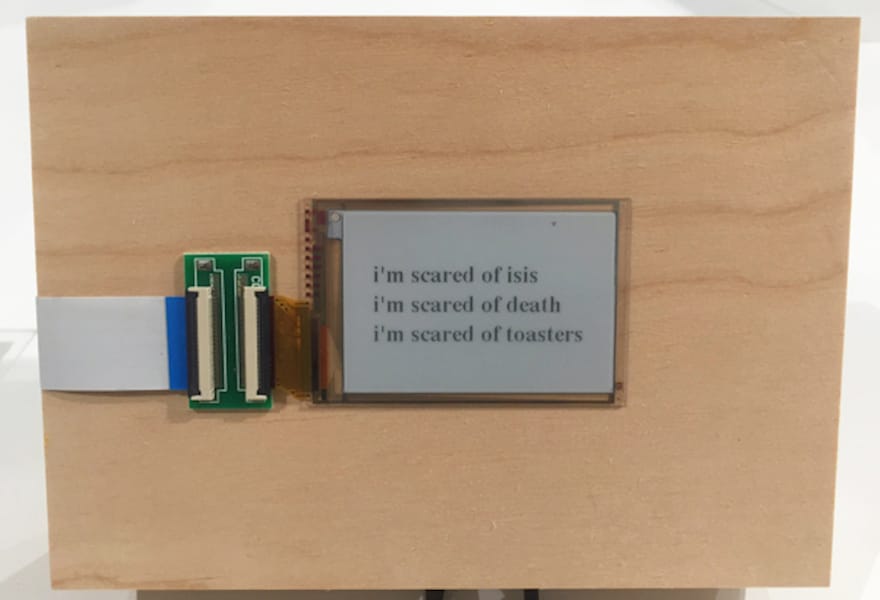

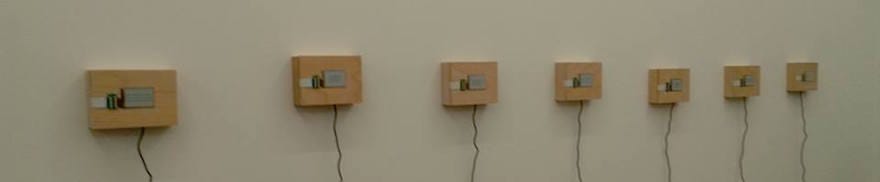

Currently wrapping up its first weekend on display at New York’s Postmasters art gallery, Glaciers is the latest art project from Sage Solitaire (2015) creator and Tharsis systems designer Zach Gage, as well as several billion unknowing co-authors. The exhibit features a collection of small e-ink screens, each displaying a digital poem generated using the top three Google autocomplete results to a specific prompt, such as “how much,” “does he want,” and “should I save.” The poems refresh once per day, meaning that like their namesake, they have the potential to change shape and meaning over time.

Though Gage is well known for his work in game design, he also has a long background as a digital artist, Glaciers being the most recent in a series of projects which focus on the questions people ask each other online. While visiting Glaciers’ opening day this past Friday, I sat down with Gage to ask him about his goals with the project. “When we build these giant systems [like Google or Twitter] on the internet,” he told me, “they amass a lot of data.” But while it might be easy to pull statistics from search engines and social media platforms, he explained, “that data is very difficult to interrogate in a meaningful way.” With Glaciers, he’s hoping to transform this data into an art piece that visitors can appreciate on a personal level.

Gage had previously approached this concept in his 2009 project Best Day Ever, which is also on display alongside Glaciers. Similar to Glaciers, Best Day Ever searches Twitter for a specific phrase—in this case, “best day ever”—and then uses an algorithm to pick one of the resulting tweets to display on its LED screen. “Early on, with Best Day Ever, I keyed into the idea that if you’re very careful with your searches, and you’re very careful about the context that your searches are presented in,” he explained, “you can make components of these large systems very meaningful to people.”

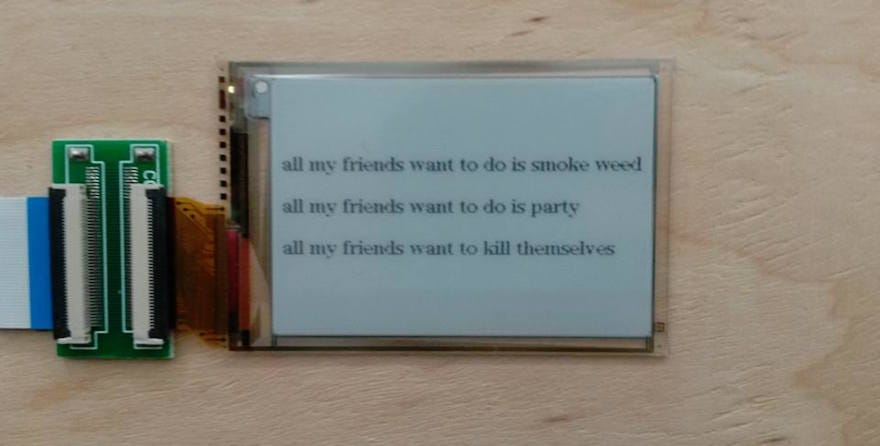

This mirrored my own experience seeing Glaciers for the first time. As I inspected each of the poems lining the gallery’s walls, I was surprised by how coherent they were, given that they written using unrelated Google searches. The poem for “is it scary,” for instance, read “is it scary to die, is it scary to fly, is it scary to skydive,” leading the reader along a single train of thought. Meanwhile, the poem for “all my friends want to” came across like a frustrated plea from a puritanical friend, reading “all my friends want to do is smoke weed, all my friends want to do is party, all my friends want to kill themselves.” Surprised by how laser-focused these unintended messages were, I asked Gage how he chose the prompts for Glaciers.

“data is very difficult to interrogate in a meaningful way.”

“Because I’ve been doing these human query things for a long time, I’ve gotten a little adept at trying to find prompts and making sure things were meaningful,” he answered. “I wanted stuff that made nice poems, were representative of the system [Google], and that I could rely upon to be interesting in the future.” I asked if any of the autocompletes he found while working on the project surprised him. “I think all of them surprised me. If they didn’t surprise me, I didn’t want to put them in the exhibit.”

As Glaciers is on display at a gallery rather than a museum, each poem is also available for sale, which Gage told me actually works into the project’s meaning. “Digital art is traditionally very momentary,” he said, saying that it often involves interacting with a piece for a minute or so and then walking away and thinking about it. “Whereas a lot of more traditional art is very passive,” he continued, explaining that when a patron buys a painting, while they may interact with it once in a while, it usually simply sits in the background of their life and becomes part of their daily experience. “So I was interested in trying to come up with a way that I could make digital art be this thing that you just pass and is part of you and becomes this monumental kind of experience.” At the same time, however, because the poem is connected to Google and will change along with it, Gage was also hoping to “be very true to its digital nature and have it be changing and really about this changing world.”

As I further explored the exhibit and noticed how deeply personal some of the poems were, frequently making mention of sexual or financial failure, I started to think about Google’s nature as an anonymous service. Because users don’t have to be embarrassed when asking it questions, it’s able to see people at their most vulnerable, making it a great way to track the anxiety of a culture over time. As Gage explained, “These are games being played by billions of people who don’t really know that they’re playing them.” The poems in Glaciers, like their real-world counterpart, have more going on under the surface than one might initially assume.

You can experience Glaciers for yourself at Postmasters Gallery in New York, running through May 7th. For more of Gage’s work, visit his website.