I was startled when a friend messaged me on Gchat the other night, asking what I was doing up so late. In truth, I was reading letters, picking through boxes, listening to answering machines and running faucets. I was turning lamps on and then off and then on again. I was going through my teenage sister’s room and I had even found Dad’s porn stash. I threw books on the floor just because I could.

Even as I write this now, I’m having trouble dissociating myself from Gone Home, “a story exploration video game” from The Fullbright Company, whose members had an influential hand in the Bioshock franchise. The premise is straightforward: You are Kaitlin Greenbriar, a college student who has been studying abroad for a year, arriving home to an empty house. That’s it. Here the creators have brushed aside escapist urgency in lieu of an experience so remarkably down-to-earth and familiar that I often found myself thinking, “I remember this.”

Once I got past the haunting quality of the house (the structure creaked and moaned as a thunderstorm shook it), I felt an extraordinary affinity toward the space. I have gone home after all. I came across pillow forts and Nintendo cartridges, a near-perfect depiction of the quintessential American sleepover. Later, an office in disarray, with rejection letters strewn about, suggested the hidden life of a frustrated writer. I was allowed insight into the Greenbriars’ most domestic moments, which were also perhaps my most domestic moments at some point in my life.

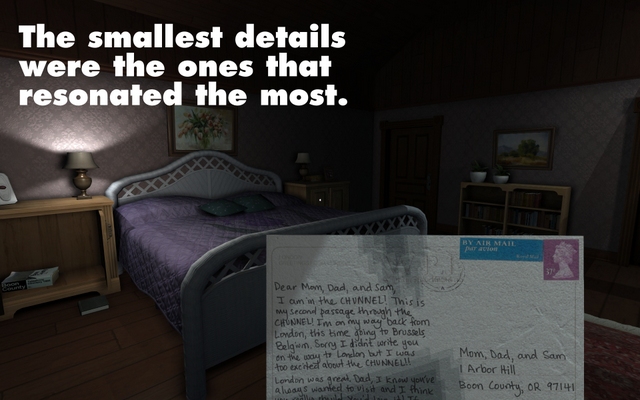

The smallest details were the ones that resonated most. A movie ticket stub for Pulp Fiction. Glow-in-the-dark stars on the bedroom ceiling. Neutral color pallets and stacks of coupons. Coming across and studying these details feels, at times, highly anthropological; the game encourages close inspection. But I very personally understood these things that I had nearly forgotten from my own upbringing. This atmosphere proffers a definition of what differentiates a home from a house: it is mundane in the best way possible.

Other than the occasional postcard from London or Amsterdam, Kaitlin’s presence within the household is minimal. Her character is left vague, which gives players the opportunity to project themselves onto her and subsequently onto the mid-1990s suburban canvas. Curiously, there are also no mirrors: if we are not allowed to establish the character within the game’s context as separate from ourselves, then we as players are more inclined to become the character. I found myself more suspended in this world, where the foreign (the house) and the familiar (my memories) so seamlessly played off one another.

As you poke around, the story of Kaitlin’s little sister, Samantha, begins to unfurl. She has seen significant change in the year that has gone by. She is a 17-year-old with creative goals, a fledgling relationship, and parents that don’t understand her. I still feel guilty having gone through her stuff.

Sam is largely understood through artifacts: a stuffed dinosaur, some hair dye. As I rifle across certain items, Sam chimes in via voiceover, as though reading from diary entries written exclusively for me, her sister. These explanations, heartfelt and well written, tie the story together, but they also jar within the hyper-realness of the suburban tableau. Everything to know is literally in front of you–except when, suddenly, it’s coming from without.

Eventually, it becomes apparent why we needed to get inside Sam’s mind. These various objects are fascinating because there’s a human connected to them. But while the clarity of the final act is important, it’s the first two acts I’ll remember. The Iranian New Wave film director Abbas Kiarostami proposed that boredom within a narrative is as important as building a story. “I want to bore you,” he has said. “Characters in [my] film are also bored … The very fact that nothing is happening creates some sort of expectation.”

What I eventually typed back to my friend was obnoxiously cryptic: “I’ve been going through someone’s home for two and a half hours.” I’m sure that she was probably a little confused.