Goodnight to the bad guy: The Freddy Krueger game that never was

You wouldn’t think that a horribly burned child murderer seeking supernatural vengeance would make a good children’s toy, but that didn’t stop the people behind A Nightmare on Elm Street. Starting soon after the film’s release in 1984, a relentless merchandising effort slapped Freddy Krueger’s distinctive face, claws, and tacky sweater on everything from action figures to yo-yo’s. The character’s conversion from terrifying to camp was cemented by a shift in tone in 1987’s A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors, with help from Aquanet-enhanced rockers Dokken, who turned soundtrack single “Dream Warriors” into an MTV staple.

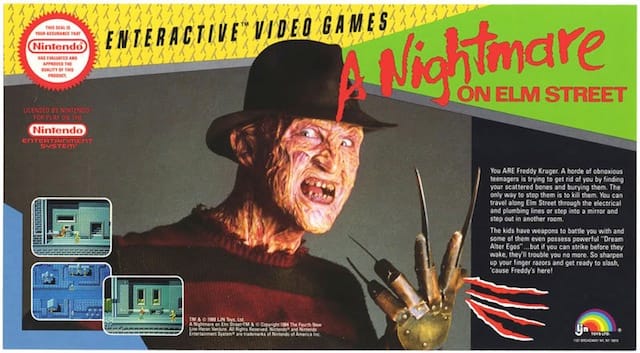

To relieve the youth of America of what little cash they had left, the next step was obvious: video games. The arrival of the Nintendo Entertainment System coincided neatly with the burgeoning film franchise’s popularity, and work on a licensed Nightmare title was underway by 1989. Published by now-defunct toy company LJN, A Nightmare on Elm Street was developed by UK studio Rare Ltd., which would go on to make the seminal Goldeneye 007.

Though Rare’s take on Bond is now the stuff of gaming legend, its initial approach to Krueger was more controversial. In early builds of the game, players were slated to take control of Freddy himself, murdering any meddling Elm St. teenagers who try to interfere with his plans.

The existence of this iconoclastic design is confirmed by a blurb in Nintendo Power #2 (Sep/Oct 1989) and more definitively by a scanned poster (above) carefully curated by the obsessives at Digital Press. Ad copy describes a fascinating, forward-thinking game in which players travel through power lines, pipes, and mirrors to ambush the unsuspecting teens. If you look closely at the enlargement above, you can see Freddy emerging from a spigot.

Sometime between its first appearance in Nintendo Power and the game’s release a year later in October 1990, everything changed. A Nightmare on Elm Street was redesigned as a forgettable, stilted platformer that was as reviled by contemporary critics as it is by modern retro reviewers. Players spend their time punching snakes, spiders and zombies that bear little relation to the actual movies, collecting Freddy’s bones in order to kill him for good. It has one half-interesting mechanic: a sleep meter, which empties as players make progress, take damage, or stand still. Emptying the meter triggers a change in graphics – things become darker, and enemies become more difficult. To clear each area, players must battle a disembodied part of Freddy’s anatomy, such as a giant clawed hand.

Oh, the 8-bit murderers we might have been!

The reasoning behind these wholesale changes is clouded by Rare’s complicated corporate history, not to mention two intervening decades. More than likely, Nintendo is to blame – the company exercised tight creative control over the games released on its staggeringly popular console, and casting players as a violent, supernatural maniac lay far beyond the pale. Gaming antiheroes were rare in 1990, and outright antagonists almost non-existent.

Nevertheless, the Nightmare franchise wasn’t giving up on gamers. In 1991’s Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare, Krueger chases one of his victims through a hallucinatory video game; the villain lounges on a couch, controller in hand, spouting catch-phrases like “now I’m playing with power!” and “you forgot the power glove!” that both evoke Nintendo.

Today, the ability to play as the antagonist is taken for granted, thanks to titles like Left 4 Dead or the popular Source mod The Hidden, a round-based multiplayer game in which players take turns hunting their opponents as a psychopathic escaped test subject who could be Freddy’s evil cousin. Horror movie fans who also love horror games now benefit from the efforts of creative, independent developers; titles like Slender: The Eight Pages and Amnesia: A Machine For Pigs evoke the gleefully terrifying can-do spirit of the B-movie directors (like Nightmare‘s Wes Craven)that invented the slasher film. Still, it’s a shame that Rare didn’t get a chance to bring its original idea – so far ahead of its time – to razor-gloved fruition. Oh, the 8-bit murderers we might have been!