Homesick is a story exploration game about people, nature, and night terrors

Imagination may be the biggest problem facing the environmental cause. There’s no dearth of it when it comes to devising solutions for our many and varied global crises, but most of us are dragging our feet in getting with the program because it’s just tough to process the big, slow changes taking place in the world around us. The primary frustration for activists trying to get the general public on board has been with engaging individuals—billions of them—who can’t see the changes from their view on the ground.

This is where photojournalist and filmmaker James Balog got the idea for the Extreme Ice Survey and the film that documented the project, Chasing Ice. The primary goal of EIS was to install heavily weatherproofed digital cameras in locales with endangered glaciers in order to take time-lapse shots over periods of several months. Chasing Ice arranged EIS along a slick narrative that made much of Balog’s ambition and showcased some startling hi-def images of glaciers disappearing over time.

Balog talks eagerly and often about his core mission in Chasing Ice: to allow audiences to watch climate change happen right in front of them. The hope was that as a result of the film, the argument for action on climate change would coast into people’s hearts on their awed disbelief at the magnitude of the geological change taking place on the movie screen. The images in the movie were supposed to accomplish what all the TED talks in the world couldn’t—with just the right amount of post-production polish to keep our brains locked in.

Yet admirable as this effort was, it doesn’t seem to have had any impact on popular discussion surrounding environmentalism. Most likely, the directness of the documentary approach only attracted moviegoers who already shared Balog’s worldview, and their sense of duty was discharged upon leaving the theater and agreeing with Balog that climate change was indeed happening.

So what chance does another populist medium stand of winning hearts and minds to the environmentalist cause? Homesick, it seems, has stepped in to test the steadily rising waters. (In order to talk about how, I’ll have to discuss aspects of the story that aren’t revealed until late in the game. If you prefer to go in completely cold, consider coming back here after you’ve played Homesick.)

Homesick is a story exploration game that takes place in a destroyed and abandoned housing complex. It’s not clear exactly what happened to this place, but from the look of it, the building is recovering from a recent decades-long vacation at the bottom of the ocean. The tiled floor is awash with mud and dirt, and the litter of paper documents left behind are rippled and dotted with water spots. Large strips of wallpaper curl down from the walls that aren’t just bare concrete, and from cracks between the tiles near the building’s large windows, grass and flowers have begun to grow (inexplicably, as the floor you’re exploring is several stories up).

happy people once lived in this dark, moldy place

You wake up alone one morning and begin poking through the detritus that used to decorate the lives of several of your neighbors. With what’s left, you can find out a little bit about each unit’s former residents. One family had a painting of a table hung in the main bedroom onto which a child had scrawled two stick people sitting down for dinner. Another tenant displayed a photograph of two women hugging and smiling behind the front door. It’s hard to imagine that happy people once lived in this dark, moldy place, but the evidence is right there, pinned up on the wall or tucked into a bookshelf.

But you don’t have the run of the place just because the building is abandoned. Locked doors halt your progress in most areas, and your exploration is limited by a puzzling inability to tolerate the bright sunlight flooding in through the big windows in the exterior hallways. For some doors, it’s simply a matter of finding keys, but for others … well, you have to trigger a nightmare in which you try to escape big, oily things by blasting through doors with an axe. You know, normal stuff.

By some weird twist, those doors you knock down in dreams become open to you after you wake up. This is the game’s basic cycle: enter a new area, try to learn a bit about the place from the scant new materials you find, and solve a simple (but often obscure) puzzle that will allow you to move to the next area.

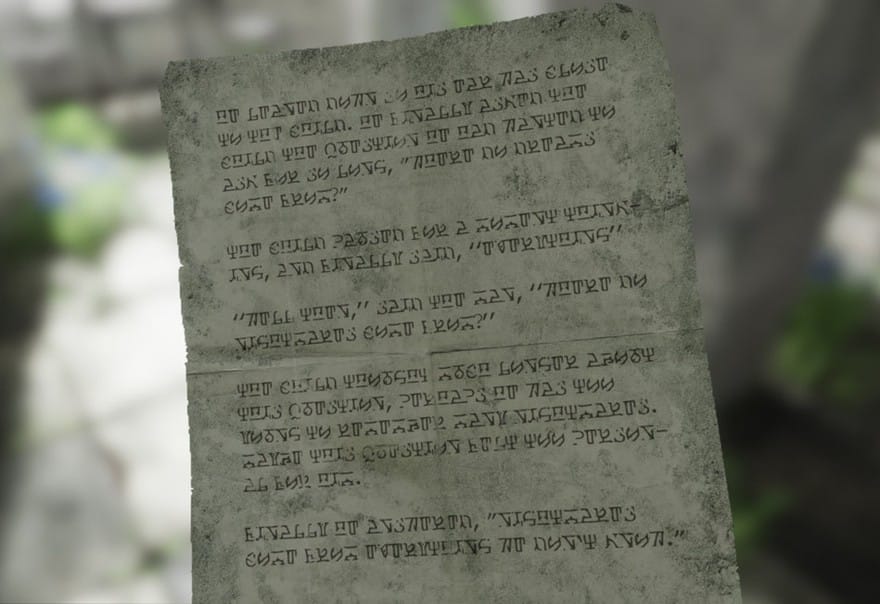

The big hang up with actually learning much as you explore the building is that of all the written documents you can find, none of them are readable to you at the start of the game. Every book and letter is written in a strange code that your character can’t decipher, and much of the early game’s exploration is consumed by picking up documents and seeing if there’s an opportunity to decode the cryptic script. A dedicated player could probably break the cipher on her own, but even then, she wouldn’t get roman characters until late in the game.

While frustrating at first, ultimately, only having a handful of nervous suspicions about what has happened contributes well to the atmosphere of mystery that pervades the game. In fact, Homesick’s narrative almost works best without all the books and letters to flip through, when it’s considered as a simple image: a sole, weak and lonely person wandering slowly around the ruins of an old home. Imagined as a single frame, Homesick is heartbreaking.

When you finally do learn to read, you read ravenously, bingeing on everything that you missed out on earlier. You learn of one family that has been trying to adopt a child despite their extended family’s insistence that it is a bad idea. One woman misses her life back on the farm with her family, and she wishes she could return to help. Another former tenant believes that the company he works for is involved in dangerous and illegal operations. In the various isolated stories in the lives of your neighbors you read, a bigger story emerges that involves a community of the future trying to fight back against impending environmental doom—a community fraught with problems that will sound very familiar to players today.

insanity that can’t be recognized until it’s too late

Homesick’s contribution to the cadre of games that register and respond to environmental issues isn’t just that something bad is going to happen if we don’t stop using fossil fuels. True, something bad has happened in Homesick, and it appears to be the result of irresponsible environmental practice. But the story that Homesick tells—of a quasi-utopian community founded on a corporation that’s involved in dirty business—seems more frustrated with big business’s monomaniacal focus on growth and expansion at any cost. It’s a kind of insanity that can’t be recognized until it’s too late—until the worst has already happened.

The human cost of this economic philosophy is also readily apparent in Homesick. We’re certainly not talking about sweatshops and slavery here, but the lack of consideration for the lives of the people this economic experiment would affect was a failure of Pruitt-Igoe proportions. Despite the talk of encouraging a healthy community that you read about in one of the newspaper articles, all of the rooms and letters tell stories of isolation and disappointment. The failure of this project was written in its DNA.

We’ve seen games that court environmental issues before. thatgamecompany’s Flower is a notable relative to Homesick, with its streamlined design and natural vistas that attempt to mash emotional buttons. In your investigation of a destroyed civilization, Homesick may also remind players of Ice Water Games’s Eidolon, except more contained and much tougher on your GPU. But by getting players invested in the ground-level human impact of reckless economic policies and attitudes toward the environment, Homesick is more than a middleweight competitor when it comes to focused political sparring.

Homesick isn’t a perfect game, but it succeeds in fostering a sense of curiosity that will carry you to the end, and its slow drip of sadness and wonder can be intoxicating. Where the writing feels shaky, you’ll forgive Homesick because of its ability to achieve on an emotional level. In the end, Homesick is a solid iteration in the brand of videogame storytelling that writes moving and politically charged narratives onto environments you can explore.