This piece is part of our Future of Genre series. Read more here.

Adam “Keits” Heart—creator of Divekick¸ tournament veteran, and tournament runner—outlined for me in an email what he thought was necessary not only to win in Street Fighter 4, but to begin really learning how to play. His bulleted list begins with learning the basic movements—your crouches, walks, and jumps—and ends with “knowing which of your fast or long range moves can punish your opponent’s unsafe behavior.” His list, all told, spans 20 segments, some which could easily be broken out into their own subsets. “There are two sides to fighting games that I deeply enjoy,” Heart wrote:

The first side is the mental game that I play against another seasoned opponent…The other side is the technical aspect of play. While I enjoy this side of fighting games, I recognize that a massive number of players who enjoy the mental half of the game are put off by the technical side of the game. Even if they have the potential skill to practice, grind, and learn the execution and the combos, what if they don’t have the time? Where is the fighting game for those players?

The closest I could think of was Bushido Blade, the old PlayStation game with a samurai fixation. Though it has its technical elements—which include a cast of speed-to-strength characters and weapon selection—there’s no life bar, no time limit, only two combatants in an unusually spacious, peaceful environment. The game’s short rounds are ill-suited for the dated technology: the loading screen often takes longer than the match itself. Because amid the game’s forest of blocky bamboo, a single confirmed hit on body or head meant instant death.

Even in 1998, instant death was certainly nothing new in gaming: TV Tropes even has its own page dedicated to the one-hit kill, a list of fighting games included. But while Bushido Blade viewed the one-hit kill as a sign of realism or samurai-driven honor, these examples are usually relics of unbalanced or frustrating mechanics; if not, they’re often too risky to rely on.

Mark Essen—or Messhof, the creator of Nidhogg—referenced Great Swordsman, a 1984 Taito game of one-hit kills achieved through fencing, kendo, and gladiatorial combat. “I really liked how it was a slow-paced fighting game that was all about spacing… you feel all the whiffs from a misplaced attack because counterattacks are often the way you win.” Essen’s statement stood out to me, because it’s obviously rampant in a trio of recent games—Divekick, Nidhogg, and Samurai Gunn—that an instant can mean even faster death at the hands of a ready opponent.

One of the most celebrated moments of fighting game history is this legendary match between Daigo Umehara and Justin Wong at EVO in 2004, in which a low-health Daigo (as Ken) is within one hit of being killed—and correctly predicts and parries every hit of Chun Li’s combo, only to counter and turn the battle. Obviously, this sort of play is outside the reach of those players that grasp, prefer, or can simply only manage the mental aspect that Heart referred to. Daigo and Wong are still held up as legends of their field, and as each year passes, the ranks grow quietly stronger. But there are still legions of fans—myself included—who can’t even manage to pull off all of the tutorial links for Ryu, joystick resting in frustrated hands, let alone think about successfully parrying a hyper combo, or taking advantage of a dropped combo, or even beginning to fathom the timing involved in creating a combo that could, in theory, get dropped.

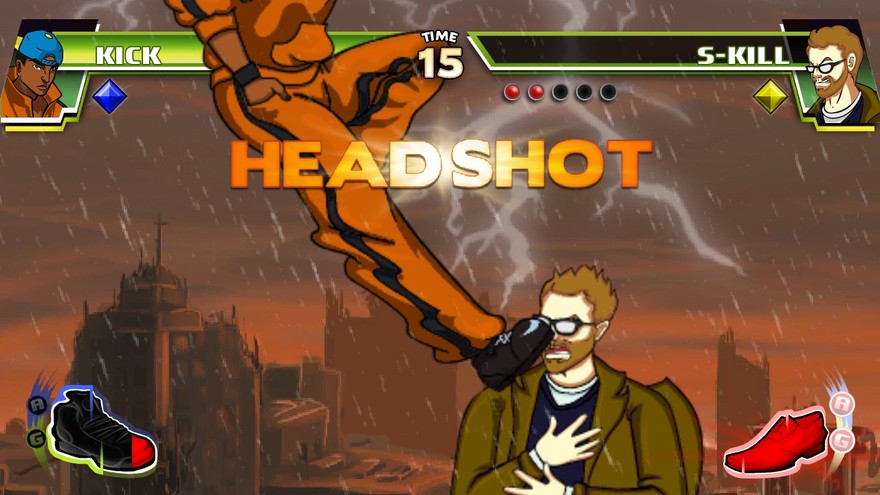

This is why it’s so easy to get excited about this new wave of “stripped down” fighters. When you reduce a game—stripping it not of superfluity, but of the entrenched technical aspects—you’re left with games that appeal to the heart, to the instinct, to the player not as an expert, but a novice. Divekick’s two-button controller and gameplay might first seem like a gimmick, but it essentially reduces a player to two hands attached to a gut: one that attempts to predict and out-perform an opponent reduced to the same. Nidhogg’s purity is spiced up by rounds that are won by distance, not combat, and feature a traditional control scheme that would have felt at home on an early console: directions, jumps, attacks.

And, truthfully, these can all be used in complex manners: Essen “didn’t want any set of moves to be too inaccessible unless you’d practiced them. The moves in the game are all context-based, like if you attack with a sword you lunge, if you attack in the air you divekick, if you press up you move your sword up, if it hits another sword it disarms.”

That idea of context is a useful one. It can be frustrating to introduce others to a complex system that has built up over time no matter the medium. When you play a game that willingly brings to the table its own context—even a context built on decades of a fighting genre, or, in Nidhogg’s case, fencing—you play an easily understandable, digestible reduction.

And in the reduction, these games essentially democratize what is so fantastic about that moment between Daigo and Wong. When Daigo parried and performed a combo, he was creating his own, incredibly technical, incredibly impressive one-hit-kill. He and Wong, for a moment, existed in a space where life bars were a nonexistent component, rendered inert by the technical play before it. By removing the technical, these games turn the most basic action—be it kicking, stabbing, slashing, or shooting—into the potential to be just as extremely satisfying as that clip. Reduce the technical; take away the life bar. And on the couch or at tournaments, amidst friends and equals alike, we can all be champions.

Check out all of Adam Heart’s commandments for play Street Fighter 4 over on our companion piece on Tumblr

Header by Zach Kugler