How the Zen videogame Tengami destroys FPS culture

I first played Tengami on an iPad at IndieCade East last February. Sound-canceling headphones erected a barrier between me and the packed show floor. The anxiety that fueled my desire to demo every game on the floor that weekend was almost forcibly quieted by my avatar’s patient, measured paces. As he walked, I listened to the wind and to the snow crumbling under his wooden sandals. My eyes followed the violet veins of ink that bled skyward in the background, and the faraway hustle and bustle of the hundreds of gamers all around me faded more quickly than I had anticipated. Once a skeptic, I was quickly converted. This unique effect is what has led many to label Tengami a “Zen game.”

Zen: today the word evokes a waiting room at a spa, complete with scented candles and a trickling plug-in fountain. To many, “zenning out” involves relaxing; laying in the bath and listening to Brian Eno, or staring at a looping optical illusion with the aid of a liberally packed bowl.

“Zenning out” implies “zoning out”—but in reality, Zen tradition involves very little of that. Typical Zen meditation entails intense concentration over seemingly simple k?ans. The most famous example is a Chinese k?an J.D. Salinger famously used as the epigraph to Nine Stories: “What is the sound of one hand clapping?”

But beneath the simple conceit lies complexities, much like the intricate mechanisms folded within the pages of a pop-up book.

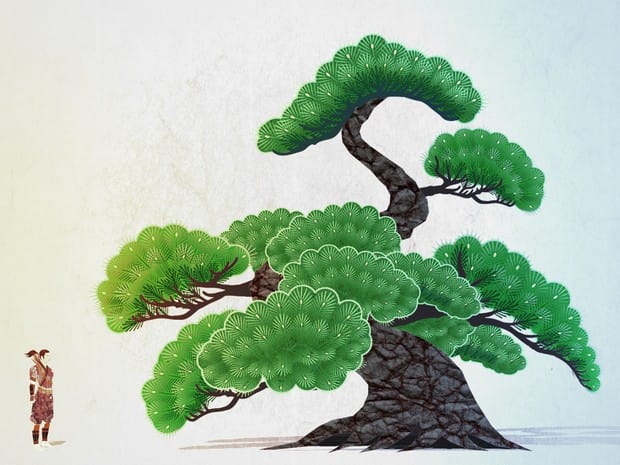

Just as a good short story has no one definitive interpretation, Zen koans are not meant to have one true answer. The point is not to solve a riddle, but to open yourself to new ways of thinking. In that regard, Tengami is far more of a “Zen game” than people realize. The central mechanic is simple: tap the screen to guide your avatar through a pop-up book world, using concise finger swipes to fold and unfold architecture, pieces of landscape, and the pages of the game world’s foundation. But beneath the simple conceit lies complexities, much like the intricate mechanisms folded within the pages of a pop-up book.

“The game doesn’t have a literal story,” says Jennifer Schneidereit. Jennifer is Nyamyam Games’ co-founder, alongside fellow RARE alum Phil Tossell. According to Phil, Tengami is an interpretive work. “The experience you bring to it is what influences what you take away from it. From the beginning we didn’t really want to have an explicit story that we tell the player. It would kind of go against the whole experience. The almost meditative action that you do—they’re all quite slow and deliberate. Everything’s meant to reinforce that idea.”

It’s tempting to take Tengami at face value. Its introductory stage is deceptively spare; other than the main puzzles, most of your options for interaction are bits of foliage scattered about, which you can fold and unfold. Most demo-ers do so quickly and without feeling. Eventually you come across a large shrine. Its architectural intricacies lead you to wonder at the craftsmanship, and perhaps fold and unfold it with more consideration for the work that went into it. And in fact, much of the work that went into Tengami was focused around building an engine that could render the intricate folds of the popup structures.

Players lacking such natural curiosity sooner or later must take it slow by necessity. “A lot of people are very quick with the flipping,” Jennifer explained to me. “There are some puzzles where you swap out parts of the world several times. They force you to think, okay, why am I changing the world here? What is it that I’m trying to achieve? Whereas in some of the puzzles we hide things in between the folds themselves. Puzzles like this kind of prompt you to start being playful and curious with the pop-up; to go back and forth and look into it.” On a mechanical level, it’s basic puzzle-solving. On an unconscious level, it’s an exercise in mindfulness.

“The intention is to challenge assumptions,” said Phil. “People start playing and think, ‘Okay, well it’s just turning pages.’ And you start to see people get very…”

“Mechanical,” Jennifer finished.

“They flip it and they’re on to the next bit,” Phil continued. “They’re in that mentality of, ‘What’s the next goal? What’s the next goal?’ So we throw in some things that slow you down again and force you to gain this playful aspect that you otherwise wouldn’t have.”

The prominent Vietnamese Zen master Thich Nhat Hahn begins his commentary to one of the oldest recorded Buddhist scriptures by saying, “If you are a poet, you will see clearly that there is a cloud floating in this sheet of paper.” He goes on to explain that the paper could not exist without the tree from which it was made, and that that tree could not exist without the raincloud that watered it; ergo, there is a cloud in the paper. On the one hand, it’s very “Circle of Life” stuff—slow down and smell the flowers, et cetera. But on a more practical level it forces practitioners to ponder the intricacies of the world which we habitually take for granted. You realize that the existence of paper is not self-evident, but contingent on the tree, the water, the cloud. A common course is to then apply that logic to one’s own mind, one’s clothes, one’s house, neighborhood, city, country, and so on. This form of logic is common in Buddhist scripture, Zen and otherwise.

Japan’s Buddhist heritage is easy to overlook beside the neon glow of Tokyo. Jennifer, who was born in Germany, lived and worked in Japan for four years, while Phil has visited Japan several times for work purposes. The two of them have worked on Tengami in the UK since 2010, collaborating with Ryo Agarie, an Okinawa-based artist and designer, over Skype. Like many videogame players, Phil was “initially interested in anime, and manga, and games; the more modern side of Japan.” During his first time abroad he stayed with a friend in a rural part of town, where they were the only foreigners. “Nobody spoke English, and there were no signs in English. I just kind of fell in love with the place. After a while I became more interested in the traditional side of Japan; the arts and crafts, and architecture, and so on. The first time I went I was more interested in going to Tokyo and Akihabara; but then I started to visit some shrines in Kyoto.”

Jennifer worked in Tokyo for four years with an indie dev named Acquire, and made time to explore more rural areas. “A friend of mine visited me in Tokyo,” she said. “We went to Kamakura, this city outside of Tokyo. It has a lot of shrines and old temples. When you get off the train, there’s this trail leading through the forest. So you’re walking through this really deep forest, and every so often, you come across a really beautiful temple. It has this really magical atmosphere.” This experience inspired much of Tengami’s introductory stages.

Likewise, the experience of falling in love with Japan has driven Phil and Jennifer to ensure that the game delivers an authentic experience. “There’s a Japanese aesthetic,” according to Phil, “that is very very difficult for a non-Japanese company to get just right. And often when Western companies try to do ‘Japanese’ games, they end up being more Chinese, or kind of generic ‘Asian.’ The latest Tomb Raider is a good example; ostensibly it’s set in Japan, but if you look closely at it, it’s not really that Japanese. I think that’s done sometimes to make [the games] more appealing to a western audience.” Yamatai-koku, in which Tomb Raider takes place, is a legendary kingdom whose true location is contested with a vigor normally associated with Atlantis or Eden. This ambiguity led American developers to take some liberties.

With Ryo’s guidance, Phil and Jennifer have striven for a visual and narrative aesthetic that stays true to Japan’s spiritual heritage, and welcomes newcomers to the culture without diluting it. Players will stumble upon buildings based on actual structures in Japan, such as the Sumiyoshi Lighthouse and a bevy of Shinto shrines, all built during the Kamakura period (1185–1333). “We had Ryo send us over some books that had schematics of temples and shrines; diagrams of real buildings in Japan.” Many of the puzzles draw from traditional folklore. An early puzzle involves an old myth: if you’re walking through the forest and a wolf crosses your path, play a wind chime, and it will fall asleep. Another involves the sun goddess Amaterasu.

Traditionally, Japanese storytelling makes no concessions towards listeners; like a Zen koan, the facts are stated without explanation. But Jennifer insists that Tengami won’t alienate players. “Obviously people who know more about Amaterasu will have a more in-depth experience. But people who don’t know will still understand. It is authentic in many ways, but it doesn’t rub your face in it. It’s basically up to you to accept or not accept it.”

Buddhism, particularly the Zen variety, experienced a boom in the West in the wake of World War II for a variety of reasons; the closure of internment camps, the return of traumatized troops from the occupied regions of Japan, and the increasing pervasiveness of beatnik disillusionment. Today, it’s prominent both as a practice and as a religion, but it’s no longer in vogue like it once was.

But perhaps Tengami can serve as therapy to FPS-induced post-traumatic stress.

Similarly, Japan doesn’t quite fascinate Western gamers the way it once did. But perhaps Tengami can serve as therapy to FPS-induced post-traumatic stress. The game has had its equal share of embrace and dismissal at conferences like PAX. Jennifer notes that “there’s a big audience of people who will enjoy Tengami, but there’s also a big audience that will not be able to get on with Tengami. It’s too different from what they really expect from a video game.

But according to Phil: “It’s really down to the mindset of the person; if they’re open to experiencing something new. Sometimes people come over from playing a shooter, and you tell them, okay, it’s a very relaxing kind of game. And they’ll go, oh yeah, I can really use something relaxing right now—I’m all done with shooting things. There’s this insistence on pigeon-holing gamers into certain groups … but people are far more complex than that. They’re quite capable of experiencing both Gears of War and Tengami.”

It’s easy to view the world as a series of yins and yangs, zeroes and ones, left and right triggers, in other words. A Buddhist would be quick to point out that such binaries are empty, and that the world is at once infinitely more complex and simple. You can’t get a PSN trophy for enlightenment.

According to Jennifer, Tengami does include a handful of achievements. But sometimes looking beneath the fold is its own reward.